CHAPTER TWO

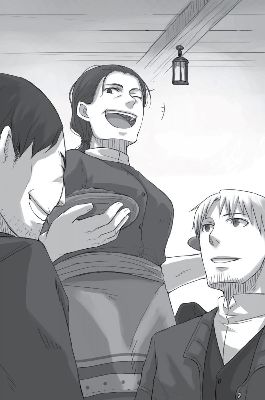

“Hah, that’s the way to drink!”

Surrounded by a happy tumult in the tavern, Holo—dressed now in her town-girl clothing—set her large rustic mug down on the table.

A saintly beard of white foam rimmed her lips, and she kept her hand on the mug’s handle as if to say, “Another round!”

One after another, the amused patrons of the bar added to Holo’s mug from the contents of their own, and soon hers was filled again.

Though no one knew who the two mysterious travelers arriving in their town so suddenly were, the pair were generous in treating the tavern’s patrons to liquor and drank full well themselves—their conduct would be well received in any village.

One of the pair was a beautiful lass to boot. They could hardly fail to impress.

“Come now! You can’t call yourself a man if you’d lose to your pretty companion!”

Holo’s hearty drinking ensured that Lawrence would be urged to drink as well, but unlike Holo, he had come for information.

He could not afford to let himself be jollied into drinking himself into a stupor.

He drank just enough not to spoil the festive mood, eating the food that was brought out and gradually making small talk with the villagers.

“Ah, this is fine ale indeed. Is there some secret to its brewing?”

“Ha-ha-ha, right there is! It’s Iima Ranel, the mistress of this tavern. She’s famous around here—her arms are as strong as three men, and she has the appetite of five!”

“Don’t tell the travelers such lies! Aye, here you are, fried garlic mutton.”

The woman in question, Iima, lightly knocked the edge of a wooden plate against the man’s head, then efficiently laid the food out on the table.

With her curly red hair tied back and her sleeves rolled up to expose her powerful-looking arms, a glance at Iima’s robust build made it easy to understand why some said she had the strength of three men.

The man’s reply, though, did nothing to answer Lawrence’s question. “Ouch, damn you! And here I was about to sing your praises!”

“So what you said just now wasn’t praise? You got what you deserved, then!”

Everyone at the table laughed. A different man continued the topic at hand. “The mistress here used to travel with a brewing jug over her shoulder!”

“Ha-ha, surely not,” said Lawrence.

“Ha! No one believes the tale when they first hear it. But it’s true, isn’t it?”

Iima, who was by now serving the drunken patrons of another table, turned around at the question. “It surely is,” she answered. Once she finished serving the other table, she returned to the one at which Lawrence sat. “I was younger and prettier then. I was born west of here in a town along the coast. But it’s the fate of such towns to be swept away by the sea, and one day a huge ship pulled into port, and soon the town was swallowed into the waves.”

Lawrence soon realized that she was talking about pirates.

“Then I got mixed up with the crowd as it rushed away, and at some point, I noticed I was carrying a brewing jug and a sack of barley,” recalled Iima, her face wistful as she looked off into the distance. She wore a little smile, but it must have been hard at the time.

A man at Lawrence’s table thrust out a mug. “Here, one for you, too, Iima.”

“Ah, my thanks. Anyway, a girl on her own wouldn’t have a prayer of finding work in some strange town, and there’d been rumors of pirates striking towns three mountains away. So I just used the river water there along with my brewing jug and barley, and I started brewing ale. And who would be the ones to drink that brew but a passing duke and his men come from afar to check on the resistance against the pirates.”

Iima was interrupted by applause. She took the opportunity to finish her ale in a single, great gulp.

“Ah, in truth, I’ve never been so embarrassed as I was that day! And to have the duke discover that this young girl with the tangled hair and dirty face had been brewing ale in the forest—why, when I asked him about it later, he told me he’d thought I was a dryad! I suppose he had an eye for such things.”

Again applause rose, this time from elsewhere. Lawrence looked and it appeared that Holo had won another drinking contest.

“But then, wouldn’t you know it—the duke said my ale was delicious! He said that as the town they were heading to had been sacked by pirates, he and his men would be unable to get decent drink there, so he asked me to travel with his company and brew for them!

“Indeed, the ambitious young maiden, Iima Ranel, thought things were finally going her way.

“But alas! The duke already had a beautiful consort!

“Ah, ’tis well, I thought—my beauty would be wasted on such a homely nobleman, anyway. Though I had hoped for a black marten fur coat.”

“So you became his personal brewer, then?” asked Lawrence—but no sooner had he asked the question than he realized that couldn’t possibly have been the case.

If she’d been the personal brewer to a nobleman, she would hardly deign to run a tavern in the village of Tereo.

“Ha-ha, no, that would be impossible. At the time, I did not know the ways of the world, so it was surely my dream—but no. But as thanks for traveling with the duke and his men, I was able to dine in his absurdly large mansion, and I was given special permission to sell ale under the duke’s name, and that was boon enough.

“So that’s where the story of the rare ale-selling maiden begins—call it ‘The Brewer Maid’s Tale.’”

Iima pounded the table once with her fist, giving everyone sitting around it a start.

“So that is how I came to wander the land, brewing and selling, selling and brewing—many things happened, but for the most part, the road was easy. But then I made a single mistake—”

“Aye, Iima visited Tereo, and tragedy followed!” someone called out with perfect dramatic timing.

It seemed to Lawrence that Iima’s tale was probably told to every traveler that passed through the village.

“I never drank the ale I brewed, you see,” continued Iima, “for I wanted to sell every drop. I’d never had a proper taste myself, but when I came to this village, I tried it for the first time, fell in love with it, and in my drunken state, stumbled right into the arms of my honorable husband!”

Lawrence laughed as he imagined the rueful grin that had to be on said husband’s face at this moment as he toiled in the tavern’s kitchen. As for the rest of the audience, they feigned tears.

“And so I became the tavern keeper’s wife. But this village is a good one—do take your time and enjoy yourselves,” finished Iima with a pleasant grin, then left the table.

Lawrence watched her go, a guileless smile on his face.

“Ah, but this is a fine tavern. I doubt you’ll find its equal even in Endima,” he said.

Endima, capital of the kingdom of Ploania, was the largest city in the northern region of the kingdom—larger even than the Church city of Ruvinheigen.

Saying something couldn’t be found even in Endima was a common way to extol the virtues of the smaller towns and villages of Ploania.

“Aye, right you are! You may be but a traveling peddler, friend, but you’ve got an eye for quality.”

Everyone liked to hear his or her hometown praised.

The men around the table all grinned and drank from their mugs in unison.

Now’s my chance, Lawrence thought.

“Indeed!” he said. “And the ale’s fine, too. Truly this village must enjoy God’s blessings,” he continued, casually slipping the statement into the flow of conversation.

Yet his words hung there like a drop of oil in water.

“Ah, excuse my rudeness,” he added.

He’d heard countless tales of other merchants who had misspoken while drinking wine in some pagan town.

Lawrence himself had made such mistakes—and the reaction he now saw was no different from his previous experiences.

“Ah, no—it’s no fault of yours, traveler,” said one of the men, as if to ease the suddenly tense atmosphere. “There is a big church here, after all.” The others nodded.

“Ours is a remote village,” another added, “so things are a bit more complicated here. And ’tis true that we owe a great deal to the late Father Franz. But still…”

“Aye, but still! Come what may, we mustn’t disobey Lord Truyeo.”

“Lord Truyeo?”

“Ah, Lord Truyeo is the guardian spirit of this village. He brings us good harvests, helps our children grow up strong and healthy, and keeps evil spirits away. He’s where the name Tereo comes from.”

“Ah, I see,” Lawrence murmured to himself. This no doubt explained the great snake in the room at Sem’s house.

He gave vague agreements and looked at Holo, who despite the great clamor that her drinking had been the center of a moment ago, looked back at him.

The spirit right before his eyes was not one to take lightly, either.

“A spirit of good harvest, eh? As a traveling merchant, I’ve heard such things. Is this Lord Truyeo a wolf spirit?”

“A wolf? Ridiculous! As though such a devil’s spirit would guard a village!”

It was quite a rebuke. Lawrence mused that he might be able to use this to tease Holo later.

“Ah, so he is—”

“A snake, merchant! Lord Truyeo is a snake!”

If one was careless, both poison fangs and wagon bed stowaways could be equally troublesome, so Lawrence didn’t see much difference between snakes and wolves. But snake spirits were quite common here in the northlands.

However, the Church held the snake as its sworn enemy. It was written in the scriptures that it was a snake that had caused man’s fall.

“I’ve heard legends of snake spirits,” said Lawrence. “One once descended from the mountains to the sea, and the path left behind it became a great river.”

“Oh, come now, you can’t put Lord Truyeo beside such things! They say he’s so long that the weather at his head is different from what’s at his tail and that he devours the moon for breakfast and the sun for dinner.”

“Aye, that’s right!” came a cacophony of voices.

“And besides, Lord Truyeo is nothing like those old fairy tales. After all, there’s a cave he dug to hibernate in not far outside of the village.”

“A hole?”

“Aye. One finds caverns everywhere, but this is one cave that bats and wolves dare not approach. There’s a story of a traveler that once went inside to prove his courage—he never returned. There’s a curse on anyone who enters—it has long been so. Even Father Franz told us never to enter. If you’d like to see it, it’s naught but a short walk from here.”

Lawrence feigned horror as he shook his head, but he now realized why the town’s church went unused.

As a matter of fact, it was something of a miracle that the church hadn’t been razed to the ground.

But after Lawrence thought it over for a moment, he realized the reason why the church was still standing.

The town of Enberch was not so very far away.

“You passed through Enberch ere arriving here, did you not?”

Just as Lawrence wondered how to broach the topic, a villager did it for him.

“You saw the giant church there, then. A man named Bishop Van is in charge there, and every generation of bishop there has been a maddening presence,” continued the villager.

“Enberch was once much smaller than Tereo, the story goes,” said another. “They, too, were looked over by Lord Truyeo until one day missionaries from the Church came, and the whole village rolled over and converted without so much as a second thought. A cathedral went up in a flash, more people came, a road was laid, and soon it was a grand town. Then they started making demands of Tereo…”

“Aye,” continued a third. “And of course, they wanted us to convert as well. But thanks to the efforts of the people here two generations ago, they managed to hold off conversion by letting a church be built. But there’s no comparison between their grand town and our little village. They let us continue our devotion to Truyeo, but in exchange we pay heavy taxes. Ask any of our grandfathers; they’ll complain about it all day.”

There were stories all the time of deals like this being made on the front lines of missionary work.

“So it was about thirty or forty years ago that Father Franz arrived,” said a villager.

Lawrence was beginning to understand the village’s situation more and more. “I see,” he said. “But I gather that a young lady by the name of Elsa now has charge of the church.”

“Ah, yes, indeed she does…”

Thanks to the ale, tongues were loosened all around.

Lawrence decided he would get answers to all of his questions in one fell swoop.

“When we stopped to pray for safe travels, I was quite surprised to find such a young girl wearing priestly robes. Are there special circumstances surrounding her, as I can’t help but assume?”

“It’s strange, isn’t it?” agreed a villager. “It was more than ten years ago that Father Franz took Miss Elsa in. She’s a good girl, but as a priest? Surely not.”

“If the responsibility becomes too heavy for her, would it not be possible to summon a priest from Enberch?” Lawrence asked.

“Ah, about that…,” said one man, who looked nervously at the fellow next to him, who in turn looked to his neighbor.

In the end, the gaze traveled fully around the table before the first man spoke again.

“You’re a merchant from a distant land, are you not?”

“Er, yes.”

“Well, then, perhaps—well, do you know any powerful men in the Church?”

Lawrence did not immediately understand why the man was asking, but he got the feeling that if he had known any, the man would have told him everything.

The man continued. “Someone that could really stick it to that lot in Enberch—”

“Hey!” Iima had appeared just a moment earlier. She rapped the man smartly on the head. “What are you saying to our guest? Do you want a beating from the elder?”

Lawrence almost laughed at the chastened man, who looked at the moment like a boy being scolded by his mother, but as he saw Iima’s gaze move to him, he quickly suppressed his smile.

“I’m sorry—it must look like we’re hiding something. But even a traveler—no, especially a traveler—can understand that every village has its own problems.”

Iima’s words carried weight, given her past spent traveling from village to village with a brewing jug on her back.

And in any case, Lawrence saw the truth in what she said.

“When travelers come through, we’d like them to eat our food and drink our wine, and when they visit another region, to talk about how nice the village was. That’s how I see it anyway.”

“I quite agree,” said Lawrence.

Iima grinned and slapped the village men on their backs. “Now then, you lot, your last job of the day is to drink and make merry!” she said, but suddenly her gaze flicked elsewhere. She then looked back at Lawrence and smiled apologetically. “I wish I could say the same to you, but it seems your companion has had quite enough.”

“She hasn’t had anything to drink in some time; I daresay she went a bit overboard.” There wasn’t much ale left in Lawrence’s own cup. He drained it in one go and stood. “I’ll return to the inn before she makes a spectacle of herself. At least she hasn’t married anyone yet.”

“Ha! She can take it from me, no good comes from a woman drinking!”

The men all chuckled furtively at Iima’s hearty comment. There seemed to be a number of stories about the subject.

“I’ll remember that,” said Lawrence, leaving some silver coins on the table.

It had cost him ten trenni to treat everyone in the tavern, which he’d done in order to quickly fit in.

Nobody wanted a spendthrift for a friend, but a generous traveler was welcome the world over.

Once Lawrence had collected Holo—who was sprawled out over a table, having seemingly drunk herself into a stupor—he left the bar, sent off with a mixture of friendly teasing and thanks.

It was fortune within misfortune that the tavern and inn both faced the town square.

Despite Holo’s slender frame, being a wolf spirit she could eat and drink tremendous amounts—extra weight that Lawrence now felt. Lifting her took effort.

Of course, that was only necessary if she truly had passed out from the liquor.

“You ate too much and drank too much.”

Lawrence put her arm around his neck, supporting her from the side. As soon as he spoke, she seemed to support her weight a bit on her own, lightening his burden.

Holo burped. “Wasn’t it my job to eat and drink, leaving barely a space for chatter?”

“Of course, I’m aware of that. But you kept on ordering the most expensive stuff.”

Though Holo’s eyes may have been sharper, Lawrence could hardly fail to notice the food and drink Holo had brought to her table.

“Ah, you’re a stingy male, you are. Ah, but enough of that—I need to lie down. It’s hard to breathe!”

Lawrence gave a brief sigh—it seemed Holo’s unsteady footsteps were not an act after all—but he himself had had a bit to drink and wanted to sit down.

The village square of Tereo, dimly lit by the lamps hanging on a few of the buildings that faced it, was deserted.

Though it had been some time since sunset, the ways in which this village differed from a larger town were clear.

When they reached the inn and opened the door, the front room was illuminated only by a single apologetic candle. The master was not there—which was hardly surprising as he’d been drinking merrily away at the same table as Holo.

Noticing the return of her guests, the master’s wife came out, taking one look at Holo’s sad state and smiling sympathetically.

Lawrence asked for some water, then climbed the creaking stairs to their second-story room.

The inn seemed to have but four rooms in total, and at the moment, Lawrence and Holo were the only guests.

Despite this, apparently a good number of people came for the spring seed-sowing and autumn harvest festivals.

The only decoration in the inn was the embroidered cloth crest, which hung in the hall, left behind by a knight that had evidently passed through long ago.

If Lawrence remembered correctly, the crest—now illuminated by a shaft of moonlight that streamed in through the open window—was the symbol of a mercenary group famous in the northlands of Ploania for killing saints of the Church.

Lawrence didn’t know if the innkeeper was ignorant of this or if he displayed the crest because of its connotations.

Looking at the crest made it clear to Lawrence just what the relationship between the Church and the village of Tereo was like.

“Hey, we’re nearly there. Don’t fall asleep yet!” As they climbed the stairs, Holo’s footing became less and less sure, and by the time they came to the door of their room, she seemed to be at her limit.

They entered, Lawrence guessing that she would be hungover again tomorrow, and he felt more sympathy than annoyance toward his companion as he managed to lay her down on the bed.

The room’s window was closed, but a few slivers of moonlight found their way through the cracks. Lawrence opened the battered window and breathed out the hustle and bustle of the day, exchanging it for the solemnly cold winter air.

Shortly after, there was a knock at the door. He turned to see the innkeeper’s wife enter, bringing water and some fruit he couldn’t immediately identify.

He asked and she explained that it was good for hangovers—though unfortunately the one most in need of the cure had already fallen fast asleep. It wouldn’t do to refuse her kindness, so he accepted the fruit gratefully.

The fruits were hard and round. Two fit in the palm of his hand. When Lawrence bit into one, the sourness was so intense it made his temples ache.

The fruits certainly seemed effective. There might even be business to be had with them. He made a mental note to look into such the next day, if there was time.

Lawrence thought back on the noisy evening at the tavern.

Holo’s speed at blending into the tavern’s mood was genuinely impressive.

Of course, he’d explained the goal to her ahead of time, as well as the part he wanted her to play.

When a pair of travelers stopped in a tavern, generally they had to either endure endless questions from the patrons or be left out of conversation entirely.

Avoiding these fates took money.

There was no easy way to obtain coin in a village like this with little in the way of commerce—but unless it was completely isolated, Tereo wouldn’t be able to survive without at least some money.

This was the main reason travelers were so welcome. Without money, they would have no reason to entertain people whose backgrounds were completely unknown.

Next, the travelers had to eat and drink heartily.

They had no way of knowing the quality of food and drink the village tavern had to offer. In the worst case, a traveler could be poisoned, and even if he didn’t die outright, he could be stripped bare and left in the mountains.

Which meant that eating and drinking indicated trust in the village.

It was important to be careful, but an interesting thing about the world is this: People tend not to be heartless if they feel they are trusted.

Lawrence had learned these things as he had opened new trade routes, but Holo’s skill at fitting into the tavern’s atmosphere was even better than his—and it was thanks to her that he was able to get answers to difficult questions much more easily than he’d anticipated.

Though Iima interrupted his last question, the visit had still gone well. If it had been a business visit, Lawrence would’ve been willing to give Holo some coin by way of thanks.

That said, it wasn’t much fun to see her accomplish the task so effortlessly when he’d gotten along perfectly well on his own up until this point.

With age came experience, he supposed.

And yet.

Lawrence closed the window and sank into contemplation as he lay himself down on the bed.

Should Holo grasp the ways of business, it would clearly be the birth of a merchant with incredible prowess. With someone who could so adroitly penetrate social circles, Lawrence couldn’t help but dream of the new trade routes he might open. Holo could certainly become such a trader.

Lawrence’s dream was to have a shop of his own in a town somewhere. For the shop to prosper, it was clear to him that two people working would be better than one, and three was still better than two. It was only natural for him to think about how reassuring Holo’s presence would be.

Holo’s home of Yoitsu was not far, and its location wasn’t entirely a mystery anymore.

Even if they were unable to discover the location of the abbey and even if they found no further clues, they would still probably find Yoitsu by the time summer came.

What did Holo plan to do after that?

Though it was only a verbal contract, he had promised to accompany her home.

Lawrence looked up at the ceiling and sighed.

He knew full well that parting was part and parcel of travel.

But it was not just Holo’s talent that he would miss. When he thought of their constant verbal sparring, the notion that it would end with their travels together caused his chest to ache.

Having thought it through this far, Lawrence closed his eyes and smiled to himself there in the darkness.

No good would come of a merchant thinking of matters outside business.

That was another lesson he had learned in his seven years of experience on the road.

What he needed to worry about was the content of his coin purse.

What he should be thinking about was how to rein in Holo’s constant gluttony.

The thoughts chased each other through Lawrence’s mind until he finally began to feel sleepy.

No good would come of it.

No good at all.

The room’s ragged blankets felt like they had been boiled in a pot, then dried in the sun. They were completely useless against the morning chill.

Lawrence was awakened by his own sneeze. A new day had begun.

At this hour, what little warmth could be found in the blanket was truly worth ten thousand gold pieces—not that he would be compensated for it.

Far from it—the warmth was like a devil child sent to devour his time. Lawrence rose and looked over at the bed next to him. Holo was already awake.

Her back was turned to him, and she looked down, as though busy with some task.

“Ho—”

He stopped in the middle of her name—her tail had suddenly fluffed out in a way he’d never seen before.

“Wh-what’s wrong?” he managed.

Holo’s ears pricked up, and at length she slowly turned around.

The sun had not yet fully risen, and the air was bluish. White puffs of her breath were visible as she looked over her shoulder.

Tears welled up in her eyes, and in her hand was a small round fruit out of which a bite had just been taken.

“…Ah, you ate it?” Lawrence asked, half-smiling.

Holo licked her lips and nodded. “Wh…what is this…?”

“The innkeeper’s wife brought it after we came back to the inn last night. Apparently it’s good for hangovers.”

Evidently some of the fruit lingered in her mouth. Holo squeezed her eyes shut and forced herself to swallow, then sniffed and wiped the corners of her eyes. “Eating this would drag me back to sobriety after a hundred years’ drinking!”

“It certainly looks like you could use its help.”

Holo frowned and threw what was left of the fruit at Lawrence, then tended to her still-fluffed tail. “’Tis not as though I am hungover every morning.”

“And thank goodness for that. It’s cold again today, I should say.”

Lawrence looked at the fruit Holo had thrown at him. It was half gone. To have eaten half of the sour fruit’s flesh in a single bite without knowing what to expect—there was no wonder she’d found the taste a shock. While it was impressive she hadn’t cried out, that might have been because she was simply unable to.

“I don’t mind a bit of cold, but no one in the village is yet awake.”

“Surely someone is up…but I daresay shops will not be open until late.”

Lawrence stood up from the bed and opened the rickety window, which seemed like it would be little use against even a weak breeze. He looked out; there was nothing but wisps of morning mist in the village square.

Lawrence was used to seeing merchants jostle for space in town square markets. The contrast made this one seem quite lonely.

“I surely prefer a livelier place,” said Holo.

“You’ll find no argument from me there.” Lawrence closed the window and looked over his shoulder to see Holo burrowing underneath the blankets to go back to sleep.

“You know, they say the gods made us to sleep just once a day.”

“Oh? Well, I’m a wolf,” Holo said with a yawn. “There’s nothing for it if no one has yet risen. If I must be cold and hungry, I’d rather be asleep.”

“Well, we are here in the wrong season. Still, it’s odd.”

“Oh?”

“Ah, it’s nothing you’d care about. I just can’t quite figure the sources of income for the people here.”

Holo had initially popped her head out of the covers with interest, but at these words, she immediately retreated back within them.

Lawrence chuckled slightly at her actions, and having nothing better to do, he thought the problem over.

Though it was true that this was a slow season for farmers, villages prosperous enough to cease work entirely during the winter were few and far between.

And based on what Lawrence heard in the tavern, they had to pay taxes to the town of Enberch.

Yet the villagers did not seem to be engaging in any jobs on the side.

The village was still very quiet just as Holo had said.

Side jobs for farming villages like this were things like spinning and weaving wool or making baskets and bags out of straw. Such work wasn’t profitable unless the volume was high, so people were generally busy at work as soon as the sun was up. If taxes had to be paid, they would have to work that much harder.

What was even stranger was the excellent ale and food at the tavern the night before.

In truth, the village of Tereo seemed, somehow, to have money.

While Holo’s nose for the quality of food was unmatched, Lawrence’s sense of smell was attuned to money.

If he could learn something about the flow of coin in this village, he might be able to do some business here, he thought to himself.

In any case, there weren’t any other merchants here, which by itself was a state Lawrence liked.

He couldn’t help but grin at himself. Here he was on a journey that had nothing to do with business, yet his mind drifted there all the same.

Just then, from outside the window, came the sound of a door creaking open.

The sound stood out clearly in the quiet morning. Lawrence looked through a crack in the window. It was none other than Evan.

But he was not entering the church as before—he was leaving it.

From his hand dangled a bundle of some kind, perhaps a meal.

As before, Evan looked around carefully, then trotted away from the church.

After he’d gone a slight distance, he turned and waved to Elsa. When Lawrence looked over at Elsa, he saw her smile and wave back in response—she couldn’t have looked more different from when she had dealt with Lawrence.

Lawrence found himself feeling a bit envious.

He watched Evan recede into the distance.

I see, he thought to himself, finally realizing why Evan was angry over the dispute between the church Elsa managed and the one in Enberch.

But Lawrence was a merchant; his vision was hardly so narrow as to regard what he’d seen as nothing more than an amusing scene.

What his eyes captured was nothing less than an understanding of what people stood to gain.

“I know where we’re going today.”

“Mm?” Holo popped her head out from under the blankets, looking at Lawrence curiously.

“It’s your home we’re searching for, and yet why am I the one working so hard?”

Holo did not immediately answer, instead flicking her ears rapidly as she sneezed and then rubbing her nose. “’Tis because I am that important, nay?”

Lawrence could only sigh at her shameless answer. “Would it kill you to spare me such talk from time to time?”

“You’re such a merchant.”

“Large profit requires large purchases. Nothing comes of buying small.”

“Hmph. What about your small courage, eh?”

It was a good comeback; Lawrence had no response.

Lawrence closed his eyes, at which Holo chuckled and then continued. “It’s harder for you to move when I am with you, is it not? This is a small village, and eyes follow us wherever we go.”

Lawrence couldn’t manage so much as an “oh.”

“If I could take action, I would—but all I would do is go to that impudent girl at the church and tear her throat out. Please, go and find the location of the abbey, truly. I may seem lazy, but I want nothing more than to go there and hear what the monk has to say.”

“Understood,” said Lawrence to calm the flames of Holo’s emotions, which burned like a sheaf of straw set ablaze.

Though she was sometimes utterly transparent with her feelings, other times she concealed her passions beneath a veil of apathy.

She was a troublesome companion, but nonetheless, her words were right on the mark. It was because she was important to Lawrence that he did all this.

“I’ll be back by midday at the latest,” said Lawrence.

“Bring me a souvenir,” came Holo’s muffled voice from beneath the blankets. Lawrence’s only reply was his usual rueful grin.

He descended the stairs and greeted the pale-faced innkeeper as he walked by the counter, then headed around to the stable, taking a sack of wheat from his wagon’s bed before going back outside.

Even without farmwork to do, people began to rise once the sun was up. Here and there were villagers tending to their vegetable patches or taking care of their pigs or chickens.

While yesterday he was greeted with only suspicion, a few people now looked at Lawrence with smiles. The night of revelry seemed to have had some effect.

A few others couldn’t manage a smile, owing to their hangovers.

But in any case, it seemed he had been more or less accepted as a traveler, which came as a relief.

The increased recognition would make it harder to move, though.

Holo’s impression had been correct. While Lawrence was impressed at her insight, he also felt a twinge of jealousy.

His destination, as he mulled such thoughts over, was naturally Evan’s water mill, where he planned to ask about Elsa.

Lawrence was not Holo. As such, he had no intention of trying to discover the nature of Evan and Elsa’s relationship.

But in order to win over the touchy, reclusive Elsa, it would be faster for Lawrence to speak with Evan, who seemed to have a better understanding of her circumstances.

As he walked down the path he had driven his wagon over the previous day, Lawrence nodded a greeting to a man who was plucking weeds from a field just outside the village.

Lawrence didn’t have any memory of the man, but apparently he had been in the bar last night as he smiled and returned the greeting.

“On foot, eh? Where’re you headed?” the man asked. It was a reasonable question.

“I was thinking of having some wheat ground.”

“Oh, the mill, eh? Careful you don’t get cheated!”

It was probably a common joke when going to the miller’s to have wheat ground. Lawrence smiled by way of reply and continued on to the mill.

A merchant was hardly ever trusted by anyone, save another merchant. Yet there were occupations that were still worse off.

While Lawrence himself had no questions about the God of the Church, who claimed that all trades and occupations were equal, he remembered that the people of Tereo had no love for the servants of that God.

The world simply didn’t go as one might wish. It was filled with hardship.

With the harvest over, the wheat fields he passed as he walked the path between the hill and the stream were rather desolate, but soon the millhouse came into view.

Evan seemed to hear the merchant’s footsteps as he approached and popped his head out of the entrance. “Ah, Master Lawrence!”

He seemed cheerful as ever, though being called “master” after having met the lad only a day earlier irritated Lawrence.

Lawrence raised the sack of wheat and spoke. “Have you a mortar free at the moment?”

“Eh? I do, but…are you leaving already?”

Lawrence handed the sack over to Evan, shaking his head.

It was reasonable to assume that if a traveler was having his wheat ground, he was making preparations to leave.

“No, I’ll be in Tereo for a time yet,” said Lawrence.

“Ah, you must! Just wait a moment, then. I’ll grind this into flour that will rise beautifully, you’ll see.”

It occurred to Lawrence that Evan might be trying to butter him up in order to win a chance at leaving the village. Evan seemed to give a short sigh of relief as he went back into the millhouse.

Lawrence followed him in and was immediately surprised.

Despite its dingy exterior, the inside of the mill was clean and well kept with three grand millstones.

“This is quite a mill,” said Lawrence.

“Isn’t it? It may not look like much on the outside, but I grind all the wheat in Tereo,” said Evan proudly as he connected the shaft that turned the mortar wheel to the shaft coming from the waterwheel.

He then extended a thin pole out the window, undoing the rope that prevented the waterwheel from turning.

Immediately the wheel creaked to life, moving the stone with a deep rumbling sound.

Checking that everything was moving as it should, Evan poured Lawrence’s wheat into a hole at the top of the mortar.

Now all they had to do was wait for the flour to collect at the plate underneath the stone.

“I haven’t seen wheat in quite some time. We’ll weigh it out later, but my guess is that the fee will be maybe three ryut,” said Evan.

“That’s quite cheap.”

“Cheap? And here I was worried you’d find it too high.”

In places with heavy taxes, Lawrence wouldn’t have been surprised at Evan’s figure being tripled.

But perhaps three ryut seemed high to someone unfamiliar with the market.

“The villagers are a tightfisted lot when it comes to grinding. But if I don’t collect in full, I’m the one to bear the elder’s ire.”

Lawrence laughed. “That’s true no matter where you go.”

“Were you a miller, too, once?”

“No, but I once did work as a tax collector. It was for the butcher tax on meat. Things like how much tax they owed for slaughtering one pig, you see.”

“Huh, so that is how it’s done, eh?”

“Cleaning meat and bones taints the river and creates a lot of garbage, so it’s taxed in order to pay for the cleanup—but of course nobody wants to pay.”

Taxation rights were auctioned off to the highest bidder by town officials. The bid went directly into the town’s coffers, and the winner could then go collect taxes at will. The more tax one could collect, the greater the profit—but if the tax collector wasn’t successful, he risked great loss.

Lawrence had done this twice when he was starting out as a merchant.

The effort collecting took and the money it yielded were totally out of proportion, he found.

“In the end, I would have to cry and beg to get people to pay. It was awful,” he said.

Evan laughed. “I surely understand!”

Lawrence knew that this story of shared hardship would go far toward winning Evan’s trust.

Well, now, he thought to himself as he laughed with Evan.

“Incidentally, you did say that all of Tereo’s grain is ground here, yes?”

“Yes, it’s true. There was a big harvest this year, so it’s hardly my fault it took so long to grind, yet they yell at me constantly!”

Lawrence couldn’t help but imagine Evan staying up all night, tending the mortar.

But Evan laughed at the memory of it, apparently happy, then continued. “What, then—have you changed your mind since yesterday? Are you planning to do wheat business in Tereo?”

“Hm? Oh well, depending on circumstances…”

“I’d counsel you to give it up,” said Evan flatly.

“Merchants are particularly bad at giving up.”

“Ha, spoken like a true merchant! But you need only go to the elder to understand. It’s been decided that the village must sell all its grain to Enberch.” As he spoke, Evan checked the progress of the mortar, carefully brushing the flour into the stone plate with a boar hair brush.

“Ah, is Tereo part of Enberch’s fief, then?” If that was true, it would make the leisurely lives of the villagers even harder to explain.

Unsurprisingly, Evan looked up and spoke proudly. “We’re their equals. They buy our wheat; we buy other things from them. What’s more, when we buy wine or clothing from Enberch, we pay no taxes. Impressive, isn’t it?”

When he passed through Enberch, Lawrence had seen that it was a town of some size.

The term poor might have been too harsh for Tereo, but the village certainly didn’t seem up to the task of confronting Enberch.

It was impressive indeed, then, for such a small village to conduct commerce with such favorable terms.

“What I heard at the tavern was that Enberch levies heavy taxes on Tereo, though.”

Evan chuckled. “That’s ancient history. Want to know why?” He folded his arms like a boastful child. It was more amusing than irritating.

“I’d love to,” said Lawrence, opening his palms in invitation.

Evan suddenly unfolded his arms and ducked his head. “Uh, sorry. I don’t know myself,” he said bashfully. “B-but still—,” he hastened to add. “I know who’s responsible for making it this way!”

In that instant, Lawrence felt something he’d not felt in a long time—the pleasure of being one step ahead of another. “Father Franz, wasn’t it?”

“Ah! Er—how did you know?”

“Call it merchant’s intuition.”

Holo would no doubt have grinned unpleasantly at him if she had been there, but sometimes Lawrence wanted to have a bit of fun. Since meeting Holo, he had always been on the receiving end of her teasing. It had been some time since he’d had the opportunity to dish it out.

“A-amazing. You’re a man to be reckoned with, Mr. Lawrence.”

“Flattery will get you nowhere. Is my wheat done?”

“Oh, er—yes. Just a moment.”

Lawrence smiled slightly at Evan’s haste, then sighed to himself.

It could be dangerous to stay in Tereo for too long.

He had seen from time to time places like this village and its neighbor Enberch.

“Ah, yes. It will indeed be three ryut. But since there’s nobody here, if you’ll keep mum about it, you don’t have to—”

“No, I’ll pay. A miller’s got to be honest, don’t you think?”

Evan held a measuring container with the newly ground wheat flour in it. He smiled helplessly and accepted the three blackened silver coins Lawrence offered. “Make sure you sift it well before you make bread with it,” he said.

“I shall. By the way—,” began Lawrence. Evan had already begun tending to the mortar now that its work was finished. “Do the church services here always begin so early?”

Lawrence expected surprise from Evan, but the boy was only curious as he turned around. “Hm?” He then seemed to understand the implication behind the question and smiled. “No, hardly. It’s not bad in the summer, but I’m sure you’ll agree it’s far too cold to sleep in the millhouse in the winter. I sleep in the church.”

Lawrence had already inferred as much, so it was easy for him to affect a natural “Ah, I see.” He continued. “Still, you seem to be quite close to Miss Elsa.”

“Hm? Ah, well, ha-ha-ha…”

If you mix pride, happiness, and embarrassment, add a bit of water, and knead until soft, you would wind up with something like Evan’s expression at that moment.

Such a recipe would certainly rise well when baked in the fires of jealousy.

“When we visited the church yesterday to ask for directions, we were treated with no small amount of disdain. She simply wouldn’t listen to anything I said. Yet this morning, she seemed as kind and gentle as the Holy Mother. Quite a surprise.”

Evan laughed nervously. “Well, Elsa’s quite short-tempered for someone as timid as she is. Her shyness makes her like a wild rat when she first meets someone. If she really wants to follow in Father Franz’s footsteps, she’ll have to stop.” He disconnected the waterwheel from the mortar and adroitly refastened the rigging to the waterwheel.

His smooth, competent movements combined with the words he spoke made Evan seem older than his years.

“But still,” he continued, “it’s been some time since she’s been in such high spirits. I suppose your timing was bad. By yesterday evening, she was quite happy. Still…it’s odd. Why didn’t she mention you had visited? That girl usually tells me how many sneezes she’s had that day.”

While Lawrence knew that Evan was only making idle conversation, he really had no interest in this.

But if he wanted to get closer to Elsa, he needed to get Evan on board.

“Surely it’s because in the end, I’m also a man,” he said.

Evan was stunned silent for a moment, then burst out laughing. Finally he managed, “So she was worried I would get the wrong idea! That silly girl!”

Lawrence looked at Evan and realized that he had much to learn from the lad despite his younger age.

Problems of this sort were more complicated even than business.

“But what would’ve made her so cheerful after being so irritable?”

Evan’s face darkened. “Why do you ask?”

“My own companion’s moods change more often than the mountain weather,” said Lawrence with a shrug.

Evan paused, recalling Holo from his memory. He ultimately seemed to accept Lawrence’s statement.

He flashed a sympathetic smile. “It must be quite rough going.”

“It surely is.”

“Sadly I don’t know how much I can explain. It’s simply that in Elsa’s case, a persistent problem has calmed down.”

“Meaning?”

“Well—,” Evan began but then cut himself off. “I was told not to talk about it to people from outside the village. If you simply must know, perhaps you might ask the elder…”

“Ah, no, if you can’t talk about it, that’s fine.”

Lawrence withdrew easily, but of course, there was a reason for that as well.

He had already gathered more than enough information.

But Evan seemed now to be worried he’d somehow aggrieved Lawrence. His face was suddenly apprehensive. He cast about for something to say. “Ah, but—I can say that if you go now, she’ll probably talk to you. She’s really not a bad person!”

Given that even the village elder had pretended ignorance of the abbey, Lawrence doubted the problem would be so simple. But it would a good opportunity to go and talk to Elsa once more.

In any case, he now had a plan.

Assuming his predictions were correct, it would work.

“Well then,” he said. “I suppose I’ll go talk with her again.”

“I think you should.”

Deciding that there was nothing further to be gained here, Lawrence said, “I’ll be off, then,” and turned to leave.

“U-um, Mr. Lawrence!” Evan called out hastily.

“Hm?”

“Is…is it hard being a traveling merchant?”

Deep in Evan’s uneasy eyes there was a determination.

Lawrence could not bring himself to snicker at the boy. “There’s no job in the world that’s not hard. But…yes, it’s quite nice at the moment.”

Lawrence admitted to himself that it was nice in a completely different way since he’d met Holo.

“I see…I guess you’re right. Well, thank you!”

Though being a miller required honesty, there was a difference between honesty and artlessness.

If Evan became a merchant, he would probably be quite popular, but actually turning a profit would take hard work, Lawrence knew.

Naturally he said none of this, simply raising the leather sack of freshly ground flour by way of thanks as he left the mill.

He ambled up the path that ran by the stream, deep in thought.

Evan claimed that Elsa would tell him even the number of sneezes she’d had in a day. The statement had left a strangely deep impression on Lawrence.

He could imagine Holo reporting the number of sighs she’d breathed in a day to convey her countless hardships and grudges.

What was the difference?

Then again, a stoic and lovable Holo would be downright eerie. Since she herself was not present, Lawrence couldn’t help but laugh at the very idea.

Upon returning to the village square, Lawrence saw a few stands now open—not enough to be called a proper marketplace, but there were more than a few villagers gathered.

Yet it seemed that the gathering was less about purchasing things and more about making affable small talk as the day began. There was none of the tense atmosphere that came with people straining to buy as cheaply as possible and selling as dearly as they could.

To hear Evan tell it, Enberch purchased all of Tereo’s wheat at a fixed price, and the people of Tereo could buy Enberch’s goods tax free.

It was hard to believe, but if that was true, it would explain the leisurely lives that Tereo’s citizens seemed to lead.

Villages were often subordinate to nearby towns, the villagers themselves trapped by the need to work day in and day out simply to afford the wine, food, clothing, and livestock that was necessary for everyday life, but that they were unable to produce themselves.

Such a village would sell its crops to a town and use the money to purchase what the villagers needed.

But in order to buy the various goods that had been brought to the town, they needed coin. The only way to raise cash was to sell their wheat to the town merchants, converting it to money, then to use the funds to buy goods from those same merchants.

The issue was that while the villagers needed money, the town merchants did not necessarily need the village’s wheat.

The power imbalance meant that the town could force the villagers to sell cheaply, then set the prices of their own goods high with things like tariffs.

The more dire a village’s financial situation, the more easily a town could take advantage of it.

Eventually the villagers would be forced to borrow money, and with no hope of repaying it, they would effectively become slaves, forced to send all their produce to the town.

To a traveling merchant like Lawrence, such slave towns represented excellent opportunities. Coin wielded terrible power in such places, and all sorts of goods could be bought for absurdly low prices.

But naturally, once a village had secured a source of money, it would be able to again resist the town’s influence, putting the town in a bad place. At that point, the arguments would become constant, endlessly repeated over this or that privilege—yet Tereo seemed free from any such fighting.

While he didn’t know how Tereo had avoided such a situation, Lawrence did have a sense of the problems and risks it faced as a result.

After buying some dried figs at a stand with a master who seemed to think that merely being open was enough, Lawrence returned to the inn.

When he got there, Holo was asleep on the bed, entirely free from the cares of the world. Lawrence laughed soundlessly.

She opened her eyes eventually as Lawrence rustled about in the room. Once her face finally emerged from underneath the blankets, the first word out of her mouth was “Food.”

Since he hadn’t been certain how long it would take them to get this far, Lawrence had been extremely thrifty with their provisions while they traveled. He decided they should finish off these first.

“There was this much cheese left? I only restrained myself because you said it wouldn’t last,” said Holo.

“Who said you could eat all of it? Half of that is mine.”

As soon as he picked up the cheese and cut it in half with a knife, Holo glared at him, her grudge obvious. “Did you not make a tidy profit in the last town?”

“Did I not explain to you that we’ve used it all already?”

In point of fact, he’d paid off his remaining liabilities in Kumersun as well as a town nearby in one fell swoop.

He did this partially as a precaution against their search for Yoitsu taking too much time—which could cause him to miss a payment deadline—and also because carrying too much cash was simply foolhardy.

Some money still remained after that, which he’d left with a trading company. A company’s power lay in its cash reserves. Of course, Lawrence was earning interest on that balance, but Holo didn’t need to know that.

“You only need to tell me once—I understand that. What I mean is, you made money, but I received nothing.”

It pained Lawrence to hear this.

The business in Kumersun got out of hand because of Lawrence’s misunderstanding, but Holo had received nothing for her trouble.

However, if he showed weakness now, the wolf’s grip would only tighten.

“How can you say something so shameless after eating and drinking so much?”

“In that case, shall we do a careful comparison of the coin you made and how much I’ve cost?”

Hit where it hurt, Lawrence looked away.

“You made quite a tidy sum with the rocks I bought from that bird woman, you did. Not to mention—”

“Fine, fine!”

With her ears able to discern any lie, Holo was worse than any tax collector.

If Lawrence struggled any further, it would only deepen the wound.

He gave up, thrusting the entirety of the cheese at Holo.

She chuckled. “Why, thank you.”

“You’re welcome.”

It was surely rare to be thanked yet to remain as annoyed as Lawrence was.

“Ah, so are your inquiries proceeding?” asked Holo.

“More or less.”

“More or less? So you’ve found half the directions we need?”

Lawrence smiled. What he’d said could be interpreted that way, he had to admit. He thought for a moment, then replied, “If I’d gone to the church, I thought I’d get the same cold shoulder we got yesterday. So I went to see Evan at the millhouse.”

“Ah, going after the person whose relationship with the girl is not uncomplicated. ’Tis wiser than I’d expect from you.”

“…Yes, well.” Lawrence cleared his throat and got to the point. “Would you give up going to the abbey?”

Holo froze. “…And the reason would be?”

“There’s something strange about this village. It feels dangerous to me.”

Holo was expressionless. She chewed a piece of rye bread on which she’d spread some cheese. “So you’re not willing to risk danger to look for my home, then?”

So that’s how it’s going to be, Lawrence thought, clenching his jaw. “That’s not—wait, you’re doing that on purpose.”

“Hmph.” Holo chewed the piece of bread rapidly, swallowing it in the blink of an eye.

It was hard to know how many words she’d swallowed along with the bread, but her face made her displeasure clear enough.

Lawrence essentially understood her desire to reach the abbey and ask her questions as quickly as she could, but perhaps those desires were stronger than he realized.

But what little information he’d gathered in the village, along with the experience he had accrued as a merchant who had seen many other towns and villages, led him to believe that it would be dangerous to keep searching for the abbey’s location while in Tereo.

After all—

“If I’m right, I think the abbey we’re looking for is Tereo’s church.”

There was no change in Holo’s expression, save for the tufts of her ears standing up bottlebrush straight.

“I’m going to go through my reasoning point by point. Are you ready?”

Holo fingered an ear tuft, then nodded slightly.

“First, Elsa obviously knows where the abbey is but is pretending ignorance. If she’s hiding that information, it means that for whatever reason, she can’t talk about Church affairs. Also, when I went to the elder’s house yesterday asking the same question, he also seemed to know—and also pretended not to.”

Holo closed her eyes and nodded.

“Next, of all the buildings in the village, only the village elder’s house is grander than the church. Yet if you’ll think back to the conversations in the tavern yesterday, you’ll see that the Church doesn’t command much respect here. The villagers worship the local snake spirit that’s protected them for ages—not the God of the Church.”

“Still,” said Holo, “did they not speak of Father Franz as someone who’d done the village good?”

“They did. The elder said the same thing. So it’s clear that Father Franz did something to benefit the village—but it wasn’t saving them by preaching the word of God, which means he did something that materially benefited them. And I found out what that was just a while ago, talking to Evan.”

Holo was prodding a piece of bread with her finger. She cocked her head.

“Essentially, he created a contract between Tereo and Enberch that is disproportionately favorable to Tereo. That’s why everybody in the village can be so idle now that the wheat harvest is over. They don’t have any financial worries. And it was none other than Father Franz who made their lives what they are by negotiating a frankly unbelievably favorable contract with Enberch.”

“Mm.”

“So the dispute between Tereo and the Church in Enberch that Evan mentioned when we were first coming into town must be about this. Generally, internal Church disputes happen over who will take over vacated priesthood or bishop posts, trouble with the donation of lands, or arguments over religious doctrine. At first I assumed that the trouble was over Elsa—being so young and a woman—taking charge of the church. But even if that’s the reason on the face of it, the true cause is something else.”

Elsa wished above all else to inherit Father Franz’s position, a man in traveling clothes had appeared at the elder’s house while Lawrence was visiting, and Evan said that Elsa’s troubles had lifted the previous day.

Based on the map of relationships that Lawrence knew all too well, he came to understand the situation quickly.

“Enberch would want to destroy the relationship that currently exists between itself and Tereo. I don’t know how or when Father Franz managed to execute the contract, but I’m sure that Enberch wants it as dead as Father Franz is now. The fastest way would be by sheer force of arms, but unfortunately Tereo also has a church. We can assume that the reason Enberch didn’t resort to force long ago is because Tereo’s church has supporters. So what to do? They need the village’s church to disappear.”

The messenger that had arrived at the elder’s house the previous day might have brought a document from some distant church that recognized Elsa as Father Franz’s successor or a letter from some nobleman promising support.

Either way, it was clear that something had secured Elsa’s position.

“The villagers here make no secret that they worship a pagan spirit. If it was to be recognized as a pagan village proper, Enberch would have the excuse it needs to attack.”

“If it was so simple as knowing how to get to the abbey, there’d be no need to lie about it,” said Holo. “But if the abbey is in the village, they must hide it.”

Lawrence nodded and made his suggestion again. “So can we not abandon this? Given the situation, the abbey’s existence would be a perfect excuse for Enberch to attack, which means the people of Tereo will continue to hide it from us. And if, as I suspect, the abbey is the church, then the monk we’ve been looking for is Father Franz. His knowledge of the old pagan tales may have been buried with him. There’s no point in stirring up trouble when there’s nothing to be gained from it.”

Additionally, Lawrence and Holo had no way of proving they were unconnected to Enberch.

Most theologians were unwilling to accept the statement “I am not a demon” as proof that one was not, in fact, a demon.

“What’s more, this involves pagan spirits. If this goes badly, we could be branded as heretics, and we would be in real trouble.”

Holo sighed, scratching at the base of her ears. It seemed like she was having difficulty reaching the place that itched.

She appeared to understand that the situation facing them was grave, but she was unwilling to give up so easily.

Lawrence cleared his throat and tried again. “I understand that you want to gather information about your home, but I think there’s danger here that we should avoid. As far as the location of Yoitsu goes, the information we gathered in Kumersun should be more than enough. And it’s not as though you’ve lost your memory. We won’t have to go far to—”

“Listen, you—,” Holo interrupted suddenly, then snapped her mouth shut as if she’d forgotten what to say.

“Holo, hear me out.”

Hearing Lawrence call her name, Holo’s lip twisted slightly.

“So I don’t misunderstand again, I want you to tell me clearly. Just what are you hoping to learn from these pagan tales?”

Holo looked away.

Lawrence didn’t want his questions to sound like an interrogation, so he carefully modulated his tone as he spoke. “Do you want to know more about the bear spirit that…er, destroyed your home?”

Still looking askance, Holo did not respond.

“Or is it…something to do with your friends?”

These were the only possibilities Lawrence could think of.

For Holo to be so stubborn, it had to be one of those two things.

Maybe it was both.

“And if it is, what would you do?” Holo’s eyes were piercing and cold.

They were not the eyes of the proud wolf stalking its prey.

They were the eyes of a cornered animal that would attack all who dared approach.

Lawrence chose his words carefully. They came to him with surprising speed.

“Depending on circumstances, there are some risks I will take.”

In other words, the potential gain had to balance out the risk.

If Holo truly needed information about the hated bear spirit that had destroyed her home or about the fates of her old friends, Lawrence would not be unwilling to help.

Despite her youthful appearance, Holo was no child, and Lawrence expected that she could evaluate her own emotions and make logical decisions. If she did so and still asked for Lawrence’s help, he was prepared to respect her decision and to take the risks that she asked.

Holo suddenly relaxed her tensed shoulders and uncrossed her legs. “Fine, then.” She continued. “It is fine. You hardly need prepare yourself for an outburst from me.”

Of course, Lawrence knew better than to take Holo’s words at their face value.

“Hark now—given my way, I would want to slap that insolent girl in the face and make her tell me everything, given what you’ve said. Also, I simply wish to know all I can about Yoitsu. Would you not likewise want to hear tell of your home?”

Lawrence nodded his agreement. Holo returned his nod, looking satisfied.

“However, I find the idea of you risking danger for my sake a bit troubling. We have a fair notion of where Yoitsu lies, do we not?”

“Ah, yes.”

“Then we need not risk this.”

Despite Holo’s statement, Lawrence remained uneasy.

While he had been the one that suggested abandoning their inquiries, he was willing to support her decision.

Hearing her accede so readily made him wonder if she was lying.

He said nothing as he thought about this. Holo sat on the edge of the bed, placing her feet on the floor.

“Why do you suppose I do not speak of my hometown to you?” she asked.

Lawrence couldn’t help showing his surprise at the question.

Holo smiled faintly, though it did not seem as if she was making fun of him. “Now and again I remember things about my hometown, things I wish to boast of. Memories I wish to tell you. But I do not, because you are always so considerate—as you are being just now. I know that to complain that you are too kind is the height of selfishness. But it is a bit difficult for me.” As she spoke, she plucked at the fur of her tail. “Honestly, if you were simply a more perceptive male, I would not have to say such embarrassing things.”

“I’m…I’m sorry.”

Holo giggled. “Still, being softhearted is one of your few good points…It’s just a bit frightening for me.”

She stood up from the bed, turning her back to Lawrence.

Her tail, thick with its winter fur, swept back and forth quietly. She hugged herself, arms around her shoulders, then looked back at Lawrence. “Here I am, lonely and helpless, yet you do not leap to devour me. Truly you are a frightening male.”

Lawrence shrugged slightly under Holo’s gaze, which seemed to challenge him. “One must be careful. Some fruits are more sour than they look.”

Holo’s arms dropped to her sides, and she turned back around to face Lawrence, smiling. “Ah, ’tis true, they can be unbearably sour. But,” she said, slowly approaching him, her smile unwavering, “are you saying I’m not sweet?”

What’s sweet about someone who does things like this? Lawrence thought to himself. He nodded immediately, as if to say, “Yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying.”

“Oh, ho, you’ve some nerve.” Holo grinned.

“Some things need to be bitter to be tasty—ale, say,” Lawrence quickly added.

Holo’s eyes widened in apparent surprise before she quickly closed them, as if she’d slipped up and made a mistake. Her tail wagged as she said, “Hmph. Children shouldn’t drink liquor.”

“Oh, indeed—we can’t have them getting hungover.”

Holo pouted intentionally and thumped her fist against Lawrence’s chest.

Leaving her hand there, she lowered her gaze.

It felt somehow like they were acting in some kind of silly play.

Lawrence took her hand gently. “Will you really give this up?” he asked slowly.

Anyone with a mind as keen as Holo’s would have already quickly separated what was reasonable from what was not.

But just as the spirits could not be understood through reason alone, emotions were not easily controlled.

It was several moments before Holo replied.

“Asking me in such a way…is hardly fair,” she said quietly, gripping Lawrence’s shirt. “If I can learn anything about Yoitsu, my friends, or that awful bear spirit, then I want to know it. What we learned from the bird woman in Kumersun was far from enough. It was like feeling thirst yet having but a few drops of water to quench it,” murmured Holo weakly.

Being very careful now that he had understood the true nature of this conversation, Lawrence replied, “What do you want to do?”

Holo nodded once. “Might I…ask this of you?”

Her words gave off the sense that if he was to embrace her, her body would be soft and yielding.

Lawrence took a deep breath and replied, “Leave it to me.”

Holo was still looking down. Her tail wagged a single time.

Though he was not sure how much of her current state was genuine, it was still enough to make him think the risk was worth the potential gain. He couldn’t help wondering if he was drunk.

Suddenly Holo looked up to reveal a dauntless smile. “Actually, I’ve got an idea.”

“Oh? Do tell.”

“Well, about that…”

Holo laid out her plan; it was simple and clear. Lawrence sighed softly. “Are you serious?”

“We won’t get anywhere being circumspect. And did I not just now ask if I could ask this of you? Did I not just ask if you would take a risk for me?”

“Still—”

Holo grinned, baring her fangs slightly. “‘Leave it to me,’ you said. It made me very happy.”

Written contracts were composed with detailed descriptions so there was no room for interpretation.

But verbal contracts were dangerous because not only could there be arguments over what had or had not been said, but also it was hard to tell whether or not one had left room for interpretation.

Not to mention that Lawrence’s opponent here was a centuries-old, self-proclaimed wisewolf.

He had utterly let his guard down, all along believing that he held the initiative.

“I have to grab your reins every once in a while, after all,” said Holo, amused.

He had only answered so gallantly because it seemed like she was depending on him.

Lawrence felt pathetic for having even dreamed such a situation existed.

“Of course, if it doesn’t go well, I’ll leave things to you. So—,” she said, smoothly taking his hand. “Right now I wish only to grab your hand.”

Lawrence slumped.

He couldn’t have brushed her hand away even if he’d wanted to.

“Right, then! Let us eat and go forth!”

Lawrence’s reply was brief but entirely unambiguous.

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login