CHAPTER THREE

In truth, if Father Franz had also been Louis Lana Schtinghilt, the abbot that Lawrence and Holo were seeking, then there was a good possibility that volumes and papers containing stories of the pagan gods were still in the church.

Naturally, if the situation was as Lawrence surmised, it was likely that Elsa would not take even the slightest risk and would disclose nothing about the abbey.

But the more important something was, the more likely it had been recorded, and the harder someone worked on something, the more difficult it would be to simply burn that work to ash.

In all likelihood, the documentation of the pagan gods remained within the church.

The problem was getting to this work.

“Pardon, is anyone there?” Just like they had the previous day, Lawrence and Holo called at the church’s front door.

However, unlike the previous day, they had not come unprepared.

“…What business have you?”

It had been but a day, so Lawrence did not know whether Elsa would be willing to open the door, but that at least seemed not to be a problem.

Yesterday she had been palpably irritated. Today her face was dark and cloudy with displeasure.

Seeing how much Elsa seemed to hate them, Lawrence found himself paradoxically fond of her.

Lawrence gave an easy smile. “My apologies for yesterday. I heard from Mr. Evan that you’ve been facing a difficult situation.”

She seemed to perk up a bit at the mention of Evan’s name, glancing through the only slightly open door at Lawrence, then Holo, then the travel-ready wagon behind them before looking back at Lawrence.

He noticed that the displeasure on her face had lessened.

“…I gather you’ve come to ask about the abbey again?”

“No, no. As far as that goes, I’ve already inquired with the elder, who also said he knew nothing of it. It is possible that the information I got in Kumersun was mistaken. The source was a bit eccentric, truth be told.”

“I see.”

Though Elsa may have thought she had succeeded in her deception, a merchant’s eyes were keener than that.

“Thus, though it be a bit earlier than we expected, we’ll be moving on to the next town. As such, we’ve come to pray for safe travels.”

“…If that is the case…” Though she seemed suspicious yet, Elsa slowly opened the door. “Come in,” she said, inviting them to enter.

The door closed with a thud once Holo followed Lawrence into the church. They were both dressed in traveling clothes with Lawrence even carrying a knapsack over his shoulder.

Having entered the church from the front, they found themselves in a hallway that extended from the left to the right. Across the hallway was another door. Church construction was the same no matter where one traveled, which meant that the door directly ahead of them was the sanctuary. To the left would be the priestly offices or study with the residence to the right.

Elsa pulled up her cassock and walked around the two, opening the door to the sanctuary. “This way, please.”

Upon entering, Holo and Lawrence found the sanctuary to have considerable grandeur.

At the front stood an altar and an image of the Holy Mother with light shining down from windows installed at the level of the second floor.

The high ceiling and lack of any chairs added to the feeling of spaciousness.

The stones of the floor were tightly joined. Even the greediest merchant would have had trouble prying them free to sell off.

The floor leading from the sanctuary door to the altar was slightly discolored from the feet that had treaded that path so often.

Lawrence followed Elsa as they made their way in and saw that the floor directly in front of the altar had been slightly worn down.

“Father Franz—,” Lawrence started.

“Hm?”

“He must have been a man of great faith.”

Elsa was momentarily surprised, but then she noticed where Lawrence was looking.

“Ah…yes, you’re right. I’d…I’d never noticed until you pointed it out.”

This was the first smile from Elsa that Lawrence had ever seen, and though it was small, it had a tenderness to it that seemed to suit a girl of the Church.

It struck Lawrence all the more, given how severe she had been at their first meeting.

The fact that he would soon cause that smile to disappear filled him with regret, as though he was extinguishing a flame that had been difficult to light.

“Then let us pray. Are you prepared?”

“Ah, before we start,” said Lawrence, putting down his knapsack, removing his coat, and taking a step toward Elsa. “I must give my confession.”

The unexpected request gave Elsa pause, but after a moment, she answered, “Er, well, in that case, there’s another room—”

“No, I will give it here, before God.”

Lawrence was adamant as he approached Elsa, and she did not quail, merely nodding. “Very well,” she said with a quiet incline of her head, every inch the devout priest.

It seemed that Elsa’s desire to inherit Father Franz’s position was not solely for the village’s benefit.

She saw Holo quietly retreat to the rear of the sanctuary, and then putting her hands together and bowing her head, she recited a prayer.

When she lifted her face again, she was a loyal servant of God.

“Confess your sins, for God is always forgiving to those who are honest.”

Lawrence took a deep breath. He was just as likely to mock God as he was to pray, but here in the middle of the sanctuary, he couldn’t help but feel a certain trepidation.

He exhaled slowly, then knelt down on the floor. “I have told a lie.”

“What kind of lie?”

“I have been deceptive for my own gain.”

“You have confessed your sin before God. Now have you the courage to tell the truth?”

Lawrence raised his head. “I have.”

“Though God knows all, he still wishes to hear you speak your transgressions. Do not be afraid. God is always merciful to those whose faith is good.”

Lawrence closed his eyes. “I lied today.”

“In what way?”

“I tricked someone using a false pretense.”

Elsa paused for a moment, then spoke. “For what reason?”

“There was something I had to know, and in order to learn it, I lied to get close to the source of that knowledge.”

“…To whom did you lie…?”

Lawrence looked up and answered, “To you, Miss Elsa.”

She was obviously stunned.

“I have now confessed my lie before God, and I have told the truth.” Lawrence stood. He was a full head taller than Elsa. “I am seeking Diendran Abbey, and I have come to ask you its location.”

Elsa bit her lip. Though her eyes were filled with hatred, she lacked the resolve of their first encounter, the strength to turn away any request.

There was a reason Lawrence had delivered his confession here.

He had to trap Elsa, whose faith was plainly deep, here—here before God.

“No,” Lawrence corrected himself. “I have lied again. I have not come here to ask the location.”

Confusion spread over Elsa’s face like oil over water.

“I have come to ask whether this is Diendran Abbey.”

“…!”

Elsa backed away, but the depression caused by Father Franz’s years of devotion caused her to stumble.

She stood before God.

Here, of all places, she could not lie.

“Miss Elsa, this is Diendran Abbey, and Father Franz was also Louis Lana Schtinghilt. Do I not speak the truth?”

On the verge of tears, Elsa looked away, as though she childishly believed that as long as she did not shake her head, her response was not a lie.

But her reaction was as good as a confirmation.

“Miss Elsa, we simply wish to know the contents of the pagan tales that Father Franz collected. It is not for business and certainly has nothing to do with Enberch.”

Elsa gave a short gasp, then snapped her mouth shut so as not to let anything escape.

“Am I wrong in thinking that the reason you wish to keep the fact that this is Diendran Abbey a secret is because Father Franz’s collected records are here?”

A drop of sweat trickled down slowly from Elsa’s temple.

It was as good as an admission.

Lawrence casually closed his fist, signaling Holo.

“What you’re worried about, Miss Elsa, is Enberch learning of Father Franz’s activities, correct? All we want is to see his writings. We want to see them badly enough that we’re willing to employ these upsetting methods.”

Elsa opened her mouth almost involuntarily. “Wh-who…who are you?”

Lawrence did not answer immediately, simply looking at Elsa.

Elsa, who planned to bear the burdens of the church upon her slender frame, looked back at him uncertainly.

And then—

“Who are we? That is a question to which it is difficult to give a satisfying answer,” interjected Holo.

Elsa suddenly looked over at Holo, as if only just realizing that she was present.

“There is a reason, though, why we—no, why I am forcing this issue.”

“…What…what reason?” managed Elsa, her voice choked as she seemed on the verge of breaking into tears.

Holo nodded. “This reason.”

Proving that they were not lackeys sent from Enberch was as difficult as trying to prove they were not demons.

But just as an angel might show its wings to prove that it was, at least, not a demon, there was a way for Holo and Lawrence to prove that whoever they were, they were not from Enberch.

Holo pulled her hood off, revealing her ears and tail.

“They are quite real. Would you care to touch them?”

Elsa’s head drooped forward. For a moment, Lawrence thought she was nodding, her hands clutched to her heart.

“Ugh—”

But then with a strange groan, Elsa fainted dead away.

After placing Elsa on the simple bed, Lawrence sighed.

He had thought that being moderately threatening would be effective, but evidently they’d gone too far.

Elsa had fainted but would probably awaken soon.

Lawrence found his eyes wandering around the room.

Though the Church certainly extolled the virtues of frugality, this room was so bare and empty that Lawrence found himself wondering if Elsa truly lived in it.

Turning right upon entering the church led to a living room with a fireplace. At the far corner of the room was a hall that ran parallel to the sanctuary, leading up to a staircase to the second floor.

The bed was on the second floor, and Lawrence had carried her up the stairs and laid her on the bed. The only other objects in the room were a desk and a chair, an open book of scripture and exegesis, and a few letters. The only decoration was a loop of braided straw on one wall.

There were two second-floor rooms; the other bedroom seemed to be used for storage.

Though he was not intentionally looking around, Lawrence could tell at a glance that the room did not contain any of Father Franz’s writings.

The storeroom contained various items used by the church throughout the year—fabric with ceremonial embroidery, candlesticks, swords, and shields. They were all covered in dust, as though they had not been used in a very long time.

Lawrence closed the storeroom’s door. He heard the sound of light footsteps coming up the stairs, and when he turned to look, he saw it was Holo.

No doubt she had walked all the way around the hallway that encircled the sanctuary, making a quick check of the interior of the church.

The vague displeasure on her face was probably not overconcern for the still-unconscious Elsa, but rather because she had failed to find any of Father Franz’s writings.

“I suppose it will be quickest to ask, after all. If they are hidden, we’ll never find them,” she admitted.

“You can’t sniff them out?” said Lawrence without thinking, but Holo only smiled at him, and he hastily added, “Sorry!”

“So, is she yet asleep? I hardly expected her to be so frail.”

“I don’t know if that’s it. I’m starting to wonder if her circumstances are more difficult than I’d imagined.”

He knew he shouldn’t, but Lawrence couldn’t help reading the letters that were on her desk. Once he finished, he had a much better understanding of the things Elsa had done to stave off Enberch’s intervention.

She had claimed to other churches that like Enberch, Tereo followed the orthodox faith and had sought the support of a nearby feudal lord in order to prevent Enberch from attacking.

But looking at the lord’s response, Lawrence noticed that he seemed to give his support more out of a debt to Father Franz than out of any trust Elsa had won on her own.

There were also letters from large dioceses that even Lawrence had heard of.

On the whole, everything was as Lawrence had guessed.

It was not hard to imagine the days when Elsa would have been frantically anticipating the letter’s arrival. Even Lawrence, an outsider, could imagine the awful suspense she must have felt.

Nonetheless, he had to guess that her greatest hardship lay somewhere else entirely.

The dust-covered artifacts in the storeroom told a tale all too clear.

Though she was holding off Enberch—with the elder’s assistance—it seemed doubtful that any of the villagers felt any gratitude.

It was certainly true that they regarded the church with a measure of disdain.

“…Mm.”

As Lawrence was thinking on it, he heard a small sound coming from the bed.

It seemed Elsa was awake.

Lawrence raised his hand to stop Holo, who looked ready to pounce like a wolf that has heard a hare’s footsteps. He cleared his throat softly. “Are you all right?” he asked.

Elsa did not jerk herself upright, but simply opened her eyes slowly. Her expression was complicated, as though she was unsure whether to feel surprised, frightened, or angry. She seemed to settle on a vaguely troubled look.

She nodded her head slightly. “Are you not going to tie me up?”

They were bold words.

“If it seemed like you were going to call for someone, I was prepared for that. I have rope in my knapsack.”

“And if I should call out now?”

Elsa looked away from Lawrence to Holo—Holo whose wish to know the location of the old tales had brought them here.

“That would benefit neither you nor us,” said Lawrence.

Elsa looked back at Lawrence, closing her eyes. He noticed her long eyelashes.

Despite her stoicism, she was still a young woman.

“What I saw…,” she began, trying to sit up. Lawrence extended his hand to help her, but she waved it off. “I’m fine.”

She looked at Holo with neither malice nor fear, as though looking at heavy clouds that were finally beginning to shed rain. “What I saw was not a dream, was it?”

“’Twould be better for us if you were to think of it as such,” said Holo.

“It is said that demons trick humans through dreams.”

Though he could tell that Holo was not being entirely serious, Lawrence was less sure about Elsa.

He looked at Holo; her annoyed expression suggested that she was at least partly in earnest.

The tension between the two had more to do with conflicting personalities, Lawrence guessed, than it did with the fact that one was a devout member of the Church while the other was a spirit of the harvest.

“So long as we reach our goal, we will disappear like a dream and trouble you no further. I ask you again: Will you show us the writings of Father Franz?” asked Lawrence, coming between the two.

“I…I still cannot be sure that you were not sent from Enberch. But if that is indeed the case…what is your goal?”

Lawrence was unsure whether he should answer this question. He looked at Holo, who nodded slowly.

“I wish to return to my home,” she said.

“Your home…?”

“But ages have passed since I was there. I have forgotten the way, and I know not if my old friends are well. Indeed, I cannot even be sure it still exists,” explained Holo plainly. “What would you do if you learned there might be someone who knew something of your home?”

Even someone who had spent a lifetime in the same village would want to know how that village was viewed by others.

It was all the more true for people who had left their homes.

Elsa was silent for some time, and Holo did not press her.

Her downcast eyes made it clear that she was deep in thought.

Despite her youth, it was obvious that she was no maiden who blithely floated through life, picking flowers and singing songs.

When Lawrence had claimed to want to confess his sins, he could tell that her solemnity was no affectation.

Though she may have fainted upon first seeing Holo’s inhuman nature, Lawrence felt she was smart enough to make the best decision given the situation.

Elsa put her hand to her chest and recited a prayer, then looked up. “I am a servant of God,” she said, continuing before Lawrence or Holo could interrupt. “But at the same time, I am Father Franz’s successor.” She got off the bed, smoothing the wrinkles in her cassock, then clearing her throat. “I do not believe that you have been possessed by a demon, because Father Franz always said there was no such thing.”

Lawrence was more than a little surprised at Elsa’s statement, but Holo’s expression seemed to say that as long as she could see the records, all was well.

Eventually Holo seemed to become aware of Elsa’s willingness to give in, and though her face remained serious, the tip of her tail wagged restlessly.

“Please come with me. I will show you.”

For a moment Lawrence wondered if she had only said this to escape, but Holo followed without question, so evidently there was no need to worry.

Once they came to the living room on the first floor, Elsa lightly touched the brick wall next to the fireplace with her fingers.

Then coming to a particular stone, she slowly pulled it free.

Having pulled it out like a drawer, Elsa turned the brick over, and a slender golden key fell into her hand.

From behind, her form was every bit the stoic girl she was.

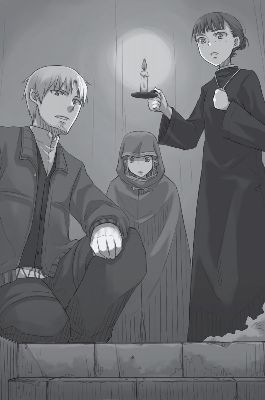

She lit a candle and put it on a stand, then turned to Lawrence and Holo.

“Let us go,” she said quietly, then walked down the hallway that continued deeper into the church.

The church was deeper than Lawrence had guessed.

Unlike the sanctuary, clean and well used thanks to constant prayer, the state of the hallway could hardly be complimented.

The candlesticks on the walls were covered with cobwebs, and little pieces of stone that had crumbled off from the walls crunched constantly underfoot.

“Here we are,” said Elsa, stopping. The direction she pointed in was probably directly behind the sanctuary.

There on a pedestal was a statue of the Holy Mother roughly as large as a young child. The Holy Mother held her hands together in prayer and faced the entrance to the church.

The space behind the sanctuary was the holiest place in the church.

Saintly remains or bones—so-called “holy relics”—and other items important to the Church were stored here.

It was the standard place for the Church to keep precious things, and so to use it to store writings on pagan stories took a good deal of nerve.

“May God forgive us,” murmured Elsa. She took the brass key in her hand and inserted it into a small hole at the base of the statue.

The tiny keyhole was not easy to spot in the gloom. Elsa turned the key with some force, and from within the statue came the distinct sound of something unlocking.

“In his will, Father Franz said that the statue could be removed from the pedestal…but I have never seen it opened.”

“Understood,” said Lawrence with a nod.

As soon as he approached the statue, Elsa backed away, worry in her eyes.

Taking hold of the statue, Lawrence hefted it with force, but it lifted unexpectedly easily.

Evidently it was hollow.

“Oof!…There.” Lawrence set the statue down beside the wall, taking care that it didn’t fall over.

Elsa looked at the space left by the statue, hesitating for a moment, but under Holo’s insistent gaze, she approached it again.

She turned the key in the opposite direction and removed it, this time inserting it into a small hole in the floor some distance away from the pedestal and turning it twice clockwise.

“Now…we should be able to lift the pedestal and stone free from the floor,” Elsa said, still crouching. Holo looked at Lawrence.

Offering any opposition now would bring her sincere ire down upon him, so he sighed and prepared himself. But at that moment, he glimpsed her making an uneasy expression.

She had made a similar expression before, only to then tease Lawrence by saying, “So you like to see me this way?” Thus he could not be sure whether or not she was truly concerned, but the possibility of it was enough to give him renewed vigor.

“It seems like the only place to take hold of it…is the pedestal. Something like this—”

Not knowing exactly how to open the floor, Lawrence looked it over, then planted his feet and took hold of the pedestal. Given the way the seams of the floor stones went, it appeared that the stone nearest the church entrance would lift.

“Hng!” Lawrence braced himself and pulled up. There was an unpleasant grinding sound, like sand in a millstone—but sure enough, the pedestal lifted, along with the floor stones.

Keeping his position, he shifted his grip and lifted with all his might.

Stone ground against stone, and rusted metal creaked as the floor lifted up, revealing a dark cellar.

It did not appear to be very deep; at the foot of the stone stairs was something that looked like a bookcase.

“Shall we go in?”

“…I will go first,” said Elsa.

It seemed that at the very least, Elsa had no intention of letting Lawrence and Holo enter first and then closing the door behind them.

And in any case, having come this far, there was no point in hesitation.

“Understood. The air seems a bit stale, so be careful,” said Lawrence.

Elsa nodded, and then holding the candle in one hand, she made her way carefully down the steep steps.

Two or three steps past the point where her head was just beneath the floor, Elsa stopped to place the candle in a hollow carved in the wall. She then proceeded.

Lawrence had worried that she planned to set fire to the contents of the room, but apparently he could relax on that count.

“You seem still more suspicious than I,” said Holo, perhaps having noticed his concern.

Elsa returned shortly.

In her hands she carried a sealed letter along with a bundle of parchment.

She was half crawling back up the steps, so Lawrence extended a hand to help her.

“…Thank you. I apologize for the wait.”

“Not at all. Are those…?” asked Lawrence.

“Letters,” answered Elsa briefly. “The books within are what you seek, I believe.”

“May we take them out to read them?” asked Lawrence.

“I would ask you to read them within the church.” It was a reasonable answer.

“I shall enter, then,” said Holo, quickly descending the stairs and entering the cellar. She was soon out of sight.

Though he didn’t follow Holo down, it wasn’t because Lawrence wanted to watch over Elsa.

“I know it’s late to be saying this, but I know that we forced you into this. I thank you and offer my apologies,” said Lawrence to Elsa, who stared vaguely down into the cellar entrance.

“Yes, you did indeed force me,” said Elsa.

Lawrence had no words in the face of her glare.

“Still…still, I think Father Franz would have been pleased.”

“Eh?”

“He was fond of saying, ‘The stories I collect are no mere fairy tales.’” Elsa’s grip on the letter she held tightened.

Those letters had probably been left behind by the late Father.

“This is my first time entering this cellar as well. I did not expect there to be so many books. If you plan to read them all, you may wish to make new arrangements at the inn.”

At her statement, Lawrence suddenly remembered that he and Holo had worn traveling clothes in order to trick her.

They had of course also settled their account with the inn.

“Ah, but you might call someone else while we go,” said Lawrence.

He hadn’t been entirely joking, but Elsa in any case seemed unamused. “I serve this church. It is my intention to embrace the true faith. I would never lay such a trap,” she said, smoothing her tightly bound hair and shooting Lawrence a stern glance, even sharper than the ones he had received upon first meeting her. “Even in the sanctuary, I did not tell a lie.”

It was true that her silence then did not constitute a lie.

Yet in spite of her resolve and the keenness of her gaze, her childlike insistence on this point reminded Lawrence of a certain someone else he knew.

So he merely nodded and agreed. “I was the one who set a trap. However, had I not done so, you would never have agreed to my request.”

“I shall remember never to let my guard down around a merchant,” said Elsa with a sigh.

Holo came staggering back up the stairs, carrying a heavy volume with her. “Hey—you—”

Lawrence hurried to help Holo, who seemed unable to bear the weight of the book and looked as though she might topple over backward. He grabbed her arms, helping her support the book.

The magnificent tome was bound in leather and reinforced at the corners with iron.

“Whew. This is certainly not something one simply wanders about with. May I read it here?” asked Holo.

“I do not mind, but please extinguish the candle when you are finished. This church is not wealthy, after all.”

“Hmph,” said Holo, looking at Lawrence.

Since none of the villagers attended services, there were no tithes.

It was easy to assume that Elsa spoke not out of malice or spite but simply because that was the truth.

Lawrence opened his coin purse, taking out some money—his thanks for having his confession heard and for having troubled her so.

“I have heard that if a merchant wishes to rise to the kingdom of heaven, he must lighten his coin purse,” he said.

“…”

He offered three silver coins.

They would be enough to buy a roomful of candles.

“God’s blessing be on you,” said Elsa, taking the coins, then turning and walking away.

Lawrence guessed that if she was willing to accept the coins, she must not consider them tainted.

“So what do you think? Can you read it yourself?” he asked Holo.

“I can. I am lucky on that count. I owe it to my exemplary conduct.”

She had gall to make jokes like that in a church.

“And which god is it that blesses people with luck according to their righteousness?”

“If you want to know, you’d best get me an offering.”

Lawrence felt sure that if he was to turn and look at the statue of the Holy Mother leaning against the wall, a bitter smile would have been on her face.

Once they returned to the inn and secured their room again—after enduring some teasing from the laughing innkeeper—Lawrence pondered what he would do next.

They had gotten Elsa to reveal her secret and discovered Father Franz’s books. So far, so good.

Though Holo had revealed her ears and tail, as long as Enberch continued to watch for a chance to strike, Elsa could not reveal the truth.

Lawrence admitted to himself that it was possible Elsa would tell the truth of Holo’s nature to the villagers in order to goad them into action, saying she was a servant of evil come to bring calamity upon the village.

But as to the question of whether she had anything to gain from such an action, the answer was an obvious “no.”

Though Elsa had fainted upon first seeing Holo’s ears, ever since she’d awoken, she had regarded Holo with neither fear nor loathing.

Truthfully she probably saved her loathing for Lawrence.

All that being the case, the next problem would be the people surrounding Elsa—Sem the village elder and Evan. If they were to learn of Holo’s nature, there was no telling what would happen.

There were a considerable number of books to read in the cellar. Holo and Lawrence would need some time to go through all of them.

If he could, he wanted to let Holo read to her heart’s content while he took responsibility for keeping her safe as she did so.

Though she had accused him of being paranoid, he felt that he had not been suspicious enough.

But there was no guarantee that taking this or that action wouldn’t rouse a sleeping snake, so to speak.

He returned to the church, thinking that in any case they needed to come up with some kind of pretense for why they were spending time there.

He found Elsa reading letters at a desk that looked far too big for her in the living room, which was every bit as painfully simple as her bedroom. She did not look as though she had secretly informed the villagers and was merely waiting for his return to spring the trap.

When he had knocked on the church’s front door, there’d been no response, so he took the liberty of coming in. There was little reaction from her when he entered the living room.

Elsa merely glanced at Lawrence, saying nothing.

He couldn’t very well just walk by her into the back of the church without saying anything.

“Are you sure you don’t want to keep an eye on us? We might steal the books, you know,” he said jokingly.

“If you planned to do that, there would be no reason not to tie me up,” she shot back correctly.

Evidently Holo was not the only tough girl in the world.

“And if you were from Enberch, you’d already be speeding back to the town on a fast horse.”

“Ah, but is that really true? There’s nothing to say you wouldn’t set fire to the books in the cellar. If the books were ash within the time it takes to get to Enberch and back, there’d be no proof.”

The exchange was both light banter and irritated conversation.

Elsa sighed and looked at Lawrence. “So long as you do not plan to bring calamity upon the village, I have not the slightest intention of raising a fuss. Though it’s true that your companion has no business being in a church, I…”

She trailed off, closing her eyes as if not wanting to see a question that had no answer.

“All we wish to do is learn more of the northlands. Your suspicion is completely understandable.”

“No,” said Elsa, her voice unexpectedly firm.

Having done so, she seemed to realize she hadn’t prepared for words that would follow this denial.

It was only after letting out a deep sigh that she was able to continue. “No…if the question is whether I feel suspicion, I admit I do. If it were possible, I wish that I could consult with someone else. But…my problem is of a larger…”

“You wish to know if my companion is truly what she claims to be?”

Elsa’s face froze as though she had swallowed a needle. “There is that as well, yes…”

She looked down, the only remaining hint of her steadfast nature being her ramrod-straight spine.

She seemed unable to continue.

Lawrence then asked, “And what else?”

Elsa did not reply.

Lawrence’s livelihood was negotiating with people.

When a person withdrew, he knew when to pursue and when to wait for that person to open up again.

This was undoubtedly the former.

“I cannot take your confession, but I may be able to give you some advice. However…”

Elsa peered at him as though from within a deep cave.

“…However, you will only be able to get sincere answers on things outside of business,” Lawrence finished with a smile. He felt that just for a moment, Elsa also smiled.

“No,” she said, “the question I have may well be best asked of a person like you. Might I ask you, then?”

When asking a favor, it is a very difficult thing to avoid seeming servile and to also preserve one’s dignity without appearing high-handed.

Yet Elsa managed it.

She was the image of the clergy.

“I cannot guarantee that any answer I give will be satisfying.”

Elsa nodded and spoke slowly, as if to be sure of every word she said. “If…if the stories collected in the books in the cellar are not false…”

“Yes…?”

“Does that mean the God we believe in is false?”

“…”

It was a simple question but an extremely serious one at the same time.

The God of the Church was omnipotent, omniscient; there were none but him.

His existence was incompatible with the many gods of the pagan tradition.

“My father—I mean, Father Franz—gathered many tales of the pagan gods of the northlands. He was suspected of heresy more than a few times, yet he was a fine priest who never once missed his daily prayers. If your companion truly is a pagan spirit, that means the God we believe in is a lie. And Father never once doubted God, not even on his deathbed.”

If so, her tragic worries were not hard to understand.

It seemed the adoptive father she’d loved and respected so had not spoken to her about a great many things.

Perhaps he had thought they were not relevant to Elsa, that such matters didn’t concern her—or perhaps he’d meant her to ponder them on her own. There was no way to know.

But to Elsa, who had no one with whom she could discuss her worries, they were a heavy burden indeed.

No matter how heavy the load, it could be carried as long as it was placed firmly on one’s back. However, all it took was a small disturbance for the whole load to come falling apart.

As soon as Elsa began to speak, her words became rapid, as though she could not hold them back if she wanted to.

“Is it because my faith is lacking? I know not. I have not the courage to rebuke the two of you, scriptures and holy water in hand. Whether that is a good thing or a bad thing—no, what it is at all, I do not—”

“My companion—,” Lawrence interjected before Elsa could corner herself with her own words. “My companion, though her true form is a giant wolf, does not wish to be called a god nor worshipped as one.”

Elsa listened quietly, desperately, a lost soul hoping for salvation.

“I am, as you see, nothing more than a merchant of no special birth. I know little of the teachings of God. I cannot tell you what is right and what is wrong,” said Lawrence, very much aware that Holo was probably eavesdropping on the conversation. “But I do not believe that Father Franz was mistaken.”

“Why…why do you believe that?”

Lawrence nodded thoughtfully, taking a moment to prepare his opinions.

It was possible that he was totally off the mark. Indeed, that possibility might have been the larger one.

But he felt a strange certainty that he understood Father Franz’s point of view.

Just as he was about to speak again, Lawrence was interrupted by the sound of a knock at the church’s door.

“…That will be Elder Sem. I imagine he is here to ask about you and your companion.” She seemed to be able to tell who was at the door by the sound of the knocking; perhaps this came from a need to tell whether the noise was someone from Enberch.

Wiping tears from the corners of her eyes, she stood, then glanced toward the interior of the church. “If you find yourself unable to trust me, you can get out there through an exit near the stove by the hallway. If you trust me—”

“I trust you. I don’t know whether I can trust Sem.”

Elsa neither shook her head nor nodded. “Then please stay in the back of the church,” she said. “I will explain that I’ve been asking you about the news from the churches of other lands. It is not really a lie…”

“I understand. I’ll be happy to share my experiences,” answered Lawrence with a smile. He was about to do as he was told and hide away in the back of the church when he noticed that Elsa had returned to her usual stoic self.

He asked himself in that moment if she would betray him. The answer came, No, she would not.

Though Lawrence did not trust in God, he did trust in those who did.

He decided he did not mind such ironies.

Lawrence walked down the dimly lit hallway. Eventually he saw the vague flicker of candlelight from around a corner.

There was no way Holo had not overheard his exchange with Elsa, so he prepared himself for whatever expression might await him as he rounded the corner.

There was Holo sitting cross-legged with an open book in her lap. She lifted her face to him, displeasure written all over it.

“Am I so very malicious, then?”

“…You’re inventing cause for offense,” said Lawrence, shrugging.

Holo snorted. “Your trepidation was plain as day; I could hear it in your footsteps.”

“Merchants only read minds, not feet.”

“…That was awful,” Holo pronounced of Lawrence’s joke. “Still, you were quite considerate to the girl.”

Lawrence both expected and did not expect this subject to come up.

He did not immediately answer, instead sitting down next to Holo, careful not to step on her tail. He picked up one of the thick books that lay there. “Merchants must always be considerate to their customers. But that’s not important. Can you hear the elder’s conversation with Elsa?”

When someone asked advice, it was important to maintain confidence and trust.

But Holo’s displeasure at the change of subject was written large on her face, and she simply looked down at the book she was reading.

Lawrence wondered to himself just who it had been, back in Ruvinheigen, that said if you have something to say, you should just come out and say it.

He wanted very much to point that out to Holo, but he could scarcely imagine the fit she would pitch if he was to do so.

However, Holo was not a completely unreasonable girl.

Before she had completely cornered herself, she relented. “She’s acting more or less as she said she would. That Sem fellow, or whatever his name was, seems to have just been checking in on her…He’s just now leaving.”

“If the elder would understand our situation, this would be a lot simpler.”

“Can you not persuade him yourself?”

For a moment, Lawrence thought Holo was mocking him; perceiving this, she glared at him.

“You overestimate me.”

“You don’t wish me to trust you, then?” asked Holo with a serious face.

Lawrence chuckled ruefully. “As ever, time is the problem. If we dally too long here, it may snow.”

“And what would be wrong with that?”

She seemed to be asking in earnest, so his reply was likewise serious. “If we were to be snowed in somewhere, would a large village or a small town be better?”

“Ah, I see. Still, we’ve a true mountain of books to get through. There’s no telling how long it will take us.”

“True, but we need only find stories that are relevant to you. If we read quickly, the two of us together should be able to make short work of it.”

“Mm.” Holo nodded, smiling as if somehow pleased.

“What is it?”

As soon as he asked, her smile disappeared.

“This is hardly the time to be asking me that,” she said with a resigned sigh. “I don’t know whether you are truly that slow or…ah, ’tis well.”

Seeing Holo waving him off, Lawrence thought back over what he had said.

Could it be? he wondered.

Had she been pleased to hear “the two of us together”?

“’Tis too late for you to say it now. I would only become angry.”

Lawrence took this as fair warning and closed his mouth.

Holo flipped through a few pages, sighing.

Slowly she let her body lean against his. “Did I not once say I was tired of being alone?” she reminded him reproachfully.

The thought nagged at Lawrence. “Sorry.”

“Mm.” Holo sniffed, then reached around and began to massage her left shoulder.

Seeing this, Lawrence had to smile.

She looked at him with a face that said, “Are you not going to help?”

Lawrence obediently brought his hand around to attend to her shoulders.

Holo sighed, satisfied, her tail brushing softly against the floor.

Even half a year ago, it would have seemed impossible to Lawrence that he would be quietly passing time with someone this way.

She was tired of being alone.

Lawrence felt precisely the same way.

Immediately after the thought passed through his mind, Lawrence heard the unmistakable sound of footsteps on stone. He hastily tried to pull his hand away from Holo’s shoulder when her hand grabbed his with uncanny strength.

“The elder has gone, but about what you were…,” said Elsa as she was coming around the corner. Lawrence had managed to withdraw his hand and put on his most neutral merchant’s face, but Holo continued to lean against him all the same.

Her body trembled slightly, as though she were suppressing laughter. At first glance, it probably looked as though she was sleeping, her face pressed against his shoulder.

Elsa took this in silently, then nodded as if having come to some kind of conclusion. “Well, then, I will return later.”

Though her voice was as hard as ever, her consideration was evident from the way she lowered it.

Once the sound of her footsteps faded into silence as she walked away, Holo sat up and laughed.

“Look, you—,” said Lawrence, but his accusatory tone went unheeded.

She laughed and laughed, eventually having to wipe a tear from the corner of her eye, then smiled maliciously at Lawrence. “Is it so humiliating then for you to be seen holding my shoulder?”

Lawrence knew that no matter how he answered, he would be falling into a trap.

He had lost the moment he’d so happily agreed to massage her shoulders.

“Though I will admit,” started Holo, her nasty smile disappearing as she contentedly lay her head against Lawrence again, “that I did wish to show off a bit.”

Lawrence suppressed the urge to pull away from her.

“I would hate for you to be taken away from me,” she said.

As a man, he could not help but feel pleased hearing this.

But he could hardly forget that it was Holo, the self-styled wisewolf, who said it.

He sighed. “You mean you would hate for your favorite toy to be taken from you.”

Holo grinned at him. “If that’s what you think, will you then play with me?”

Lawrence could only sigh.

The candle on the stand had lost its shape, and the pile of books they’d read had grown tall enough to lean upon when the church had another visitor.

Holo lifted her head, her ears erect.

“Who’s that?” Lawrence asked.

Holo giggled happily, not offering a serious reply—which meant it was probably Evan.

Lawrence didn’t have to guess why Holo was laughing.

“It’s gotten late, though…It’s dark now.”

He stood up straight and stretched, his spine popping gratifyingly.

He had gotten sucked into reading. The tales were interesting in their own right, even without the motivation of reading for Holo’s sake.

“I’m hungry also.”

“Quite. Shall we take a rest?” Lawrence let his stiff body relax as he reached for the candle. “Let’s not let Evan see your true nature. The fewer people who know the secret, the better.”

“Mm. Though that girl will likely tell him all the same.”

“I don’t know…I don’t think so.”

Elsa didn’t strike Lawrence as the kind of girl who would easily let a secret slip. Despite Evan’s statement that she told him how many sneezes she had in a day, she hadn’t mentioned Lawrence and Holo’s first visit to the church to him.

“Oh no?” came Holo’s skeptical reply. “That girl seems troubled over something. Depending on what she decides, who can say what she will do?”

“Ah, her questions about God. I suppose that is true now that you mention it.”

At the time, Lawrence hadn’t found a chance to give Elsa his answer, winding up instead lost in a book.

But as he thought on it, he wondered if that wasn’t for the best.

“Incidentally, what were you planning to tell her?” Holo asked.

“Well, I might have been completely mistaken anyway.”

“I would hardly expect a perfect answer from you.”

It was a nasty thing to say, but hearing it put so bluntly made it easier for Lawrence to answer. “The way I see it, Father Franz collected tales of the pagan gods to prove the existence of his own god.”

“Oh, ho.”

“Praying every day, day after day, yet never seeing so much as a hint of one’s god—anyone would begin to doubt, don’t you think?”

Holo—who had been thus doubted—nodded, annoyed by the memory of it.

“But if he then started to look around, he would have seen that there were many, many other gods that people worship. Does that god exist? What about this other one? It’s only natural that he would’ve started to wonder. If he could prove the existence of the gods worshipped by others, then that would mean his own God existed, too.”

Of course, this manner of thought was a complete anathema to the Church.

Shortly after Lawrence met Holo for the first time, the two had taken shelter from the rain in a church. Holo had some knowledge of Church beliefs and had been able to chat easily with the believers there—so this had to have occurred to her as well.

“Aye, but the God of the Church is a supreme being, is he not? There are no other gods before him, and he created the world—people merely borrow it—is that not what they hold?”

“It is. Which is why I believe this is truly an abbey, not a church.”

Holo’s increasingly annoyed expression was no doubt because she did not follow Lawrence’s logic.

“Do you know the difference between an abbey and a church?”

Holo was not so vain as to feign knowledge when she was ignorant. She shook her head.

“An abbey is a place for prayer. A church is a place for teaching about God. Their aims are entirely separate. Abbeys are built in remote regions with no thought given to guiding people down the correct path. The reason monks may spend their whole lives within one is that there is simply no reason to leave.”

“Hm.”

“So what do you think would be the first thing a monk would do if he began to doubt the existence of God?”

Holo’s gaze drifted.

The fish within her mind were surely swimming farther through the sea of knowledge and wisdom.

“Indeed—he would seek to ascertain the existence of the God he worshipped, which means our treatment depends even more upon what that girl decides to do,” said Holo.

“I’m glad I didn’t tell her any of this during the day. Elsa’s not a nun—she’s a member of the clergy.”

Holo nodded briefly, glancing at the pile of books.

They hadn’t yet looked at even half of the volumes in the cellar.

Though they did not necessarily have to look at every book, they still had not found the stories that Holo sought.

Had there been an index where they could have looked for gods of a certain region, that would have sped things up considerably, but as it was, they had no choice but to search page by page through the chronicles.

“Well, in any case, all we can do is search the books as quickly as we can. There is still the problem with Enberch, after all.”

“Mm. True, but”—Holo’s gaze turned to the hallway that led to the room where Elsa and Evan were—“first let us eat.”

A moment later, they could hear Evan’s footsteps as he came to invite them to dinner.

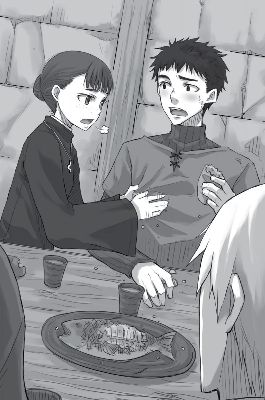

“We thank God for blessing us with bread this day.”

After saying the traditional prayer, the four enjoyed a fairly luxurious meal—owing, Elsa explained, to Lawrence’s overgenerous donation.

However, luxurious in a church meant bread enough for everyone, a few side dishes, and a bit of wine.

On the table was rye bread along with some fish Evan had caught in the river and some boiled eggs. Based on Lawrence’s experience, for a church with coffers that were hardly deep and rules that were not unstrict, it was quite a feast.

No doubt Holo was unsatisfied by the lack of red meat, but fortunately there were other side dishes for her.

“Come, don’t be so messy. Take a piece of bread, then eat it,” corrected Elsa, eliciting a shrug from Evan every time she did so. Just a moment ago Elsa had been unable to watch Evan fumbling to shell a boiled egg and had helped him with it.

Holo had watched this with a certain amount of regret, perhaps because she had already eaten her own egg. Lawrence noted this and realized it had been a close call.

“Fine, fine!” said Evan. “Anyway, Mr. Lawrence, as you were saying…” Evan’s complaining was less that he was genuinely annoyed and more that he did not want to look bad in front of Lawrence and Holo.

Though Holo was good at hiding it as she ate, she was clearly smiling.

Only Elsa seemed to be seriously concerned with Evan’s sloppiness; she sighed.

“Er, let’s see, where was I?” said Lawrence.

“The ship had left harbor and gotten past the cape where rocks lurked beneath the waves.”

“Oh yes, of course. That particular harbor was dangerous until you reached the open sea. Every merchant aboard was huddled up belowdeck, praying for their lives.”

Lawrence was telling of a time he had transported cargo by ship. Evan knew little of the ocean and was keenly interested.

“Once we learned we had safely passed the cape, we all came abovedeck to discover there were ships all around us.”

“Even though it was the sea?”

“Well, it’s only natural for there to be ships in the sea,” said Lawrence, chuckling in spite of himself.

Elsa sighed a long-suffering sigh.

Evan was the only one among them never to have seen the ocean, so his position was a bit unsteady.

But Lawrence understood what Evan had meant to say, and so he continued. “It was an amazing sight. The sea was dense with vessels, all hauling in great mountains of fish.”

“Wouldn’t…wouldn’t they run out of fish to catch?”

Holo shot Lawrence a glance of extreme skepticism, as though to say, “Even if he’s lying, nobody could be that ignorant.”

“Anyone who’s seen the sea there during that season will tell you about the black rivers of fish that run through the water.”

The herring schools were a magnificent sight. It was said that a sharpened stick thrust at random into the water would come back with three fish upon it.

It was unfortunate that short of having Evan see the sight with his own eyes, there was no way Lawrence could convey to him the truth or scale of the sea.

“Wow…I can’t really imagine it, but I guess the outside world is a big place.”

“But the most surprising thing on the ship was the food,” continued Lawrence.

“Oh?” Holo was now the most interested party.

“Yes, since there were merchants from so many different regions. There was a man from a place called Ebgod, which is near a salt lake. His bread was incredibly salty.”

Everyone looked at the bread in the middle of the table.

“I can understand making bread sweet, but his bread tasted as though it had salt sprinkled over it. It did not quite agree with my palate.”

“Salt, eh? He must have been a rich man to put salt upon bread!” said Evan, impressed.

Tereo was landlocked, and if there was no nearby source of rock salt, then it would have been a luxury item.

“Yes, but Ebgod has a salt lake. Imagine a salt river running through town and every field as far as the eye can see turned to salt. There’s so much salt everywhere that the people there enjoy salty bread.”

“Still, salty bread!” said Evan, disgust on his face.

“There were other strange things on the ship, too—like flat bread baked in the bottom of a bowl.”

A loaf’s value was in its rise—or at least, anyone used to baking bread in an oven would think so.

“Ha, surely not.”

Lawrence was pleased to hear the answer he had expected. “Ah, but if you make bread from oats, then it will turn out flat and even, will it not?”

“Well, I suppose…,” said Evan.

“Would you not eat unleavened bread, then?”

Lawrence was referring to bread that had not been blessed by the bread spirits but had rather been baked immediately after kneading.

It was unlikely that Evan had never eaten it—but he probably hadn’t enjoyed it much.

“While one could hardly call oat bread delicious even as flattery, the bowl bread was quite tasty, particularly topped with beans or the like.”

“Amazing,” said Evan, impressed, his eyes staring distantly at some far-off imagined place.

By contrast, Elsa had torn off a piece of rye bread and seemed to be comparing it to the flat bread in her imagination.

The two were highly amusing.

“Anyway, the world is a vast place with much to see,” said Lawrence, wrapping things up. Next to him, Holo had finished eating and seemed to be getting restless. “My deepest thanks to you for preparing such a feast for us,” he added.

“Not at all. It is thanks to your generous donation. This is the least I could do,” said Elsa.

If only she would spare us the slightest smile when she said so, Lawrence thought ruefully.

Nonetheless, it did seem she hadn’t felt forced to make the dinner, which gave him some measure of relief.

“So, about later…”

“If you wish to read the books at night as well, I do not mind. I know your aim is the northlands, and if it starts to snow, it will make your situation difficult.”

Conversation moved quickly with Elsa. Lawrence was grateful.

“Well, then, Mr. Lawrence—you’ll have to tell me more stories later!” said Evan.

“He already said he was in a hurry. And today you have to practice writing,” said Elsa.

Evan ducked his head, looking to Lawrence with a pained expression that begged for help.

That brief instant made Elsa and Evan’s relationship crystal clear.

“When the opportunity arises, I shall. And we’ll impose upon your church’s hospitality a bit longer then, thank you.”

“Yes, feel free.”

Lawrence and Holo stood, giving their thanks for dinner one last time before leaving the living room.

He noticed Elsa giving Holo a casual glance as they went, but Holo pretended not to see it.

“Oh, that’s right.” Lawrence turned just as they were walking out the door and looked to Elsa. “About the question you asked me earlier.”

“I will consider it on my own,” she said. “‘Think before asking,’ Father Franz used to say.”

Elsa was not the timid, scared girl she had been earlier in the day, but instead showed the stoutness of heart she would need to support the church on her own.

“I understand. If you want to hear the thoughts of another, please do come and ask.”

“I shall, thank you.”

Evan, unable to follow the conversation, looked back and forth between Lawrence and Elsa until a call from the latter put his attention to other matters.

Despite his complaints, Evan seemed to be enjoying his exchange with Elsa as they started clearing the dining table.

Though Evan seemed by turns put-upon or annoyed by Elsa’s constant corrections, he would sometimes take her hand or say her name, and the two would share a quiet smile.

It was the sort of interaction Lawrence had deliberately avoided paying attention to as a merchant.

No, he had even mocked them.

He held the sconce with its lit candle and gazed at Holo’s form in front of him there in the hallway, illuminated by the candle’s flickering light.

Eventually Holo turned the corner, and she was out of his sight.

Lawrence thought back.

He had plied the dark roads, stingy even with his candles, picking up gold coins as he traveled.

Even though he’d become desperate enough for company to begin to wish he could talk to his horse, he still had never taken his eyes from the path of those gold coins. This behavior seemed truly strange in retrospect.

He continued his slow walk down the hallway, relying on the small candle to light his way.

As he turned the corner, he saw Holo there, already reading a book.

Suddenly she spoke. “And what happened to you?”

“Hm?”

“That expression of yours—did a hole suddenly open in your coin purse?” she asked with a laugh.

Lawrence put his hand to his cheek in spite of himself. Outside of business negotiations, he was quite oblivious to the expressions his face made.

“Was I making a face?”

“Mm.”

“Oh. Wait…oh.”

Holo’s shoulders shook with mirth. “Perhaps the wine has gotten to you?”

Lawrence reflected on this; his head did feel a bit muzzy, come to think of it.

No—he knew exactly what it was that had made him fall into such a strange mood.

He was simply unsure where that left him.

“Those two certainly get along well,” he said, meaning nothing in particular by this.

He had truly not put any thought into the muttered statement.

But the moment he said it, Holo made an expression that he would long remember.

Her eyes were wide and round.

“Wh-what’s wrong?” asked Lawrence—now he was the surprised one.

But Holo merely stared, evidently too stunned to voice anything more than an inarticulate groan. Eventually she returned to herself, but merely stared off into space, an expression of deep distress on her face.

“…Did I really say something that strange?” Lawrence asked.

Holo did not reply, her fingers restlessly flipping corners of the book’s pages.

Her expression was troubled, but whether she was stunned or angry or at a loss, it was hard to tell. Just looking at her, Lawrence himself was becoming upset.

“Er—well, now—look, you—,” she started.

At length, she glanced over at him. Something in her eyes looked as though she had given up on something.

She seemed so deeply distressed that Lawrence dared not ask what was wrong again. If he did, she might be likely to collapse on the spot.

What was worse, when she continued to speak, he didn’t understand what she was saying.

“I, er…for the most part, I…I know well my own good points and the bad as well.”

“Ah, oh.”

“But…er…perhaps it is strange to say so myself, but…having lived so many years, I can laugh off most things. Of course, sometimes I cannot. You should know this quite well yourself…yes?”

Somehow, Holo seemed to have been forced to make a difficult decision. Lawrence drew back a bit and nodded.

Holo put down the book she held, sitting cross-legged and grasping her ankles, her head low. She seemed in truly dire straits, avoiding looking at Lawrence as though it would blind her to do so.

Seeing her on the verge of tears, Lawrence could not help but feel deep concern. Then she spoke.

“Come now, you—”

Lawrence nodded.

“I…I wish that you would not sound so envious when you speak of them,” she said.

Lawrence stood there, stunned, as if he’d been walking a crowded street only to sneeze and find everyone around him suddenly vanished.

“I, too…no, I understand. I understand, but I did not want to say it…that seen from the outside, we, too, must look quite the fools.”

Quite the fools—the implications of the term sunk heavily into Lawrence’s ears.

It was a terrifying sensation, not unlike having completed a large business deal only to discover the calculations had been performed in the wrong currency.

Their relationship was something that had to be considered, yet considering it was terrifying.

Holo forcedly cleared her throat, scratching on the floor loudly with her fingernails. “I myself do not…I do not know why it is so embarrassing. No, I should even be angry—‘those two certainly get along well,’ you said so enviously, so what am I—”

“No,” said Lawrence, cutting her off.

Holo glared at him like an angry child looking at an adult.

“No, I understand,” he continued. “I think.”

Holo’s face became visibly darker at the way his voice grew hoarse at the end of his statement.

“No—I do understand. I do. I always have. I just didn’t want to put it into words.”

Holo began to rise, now on one knee rather than cross-legged. Her gaze was less doubtful and more of a warning—she seemed to be saying that she would not take betrayal lightly.

She might well fly at Lawrence, should he speak clumsily.

Her state seemed to be pushing him into saying something he normally would not have wanted to say.

“I was envious, but not of their relationship itself.”

Holo hugged her knee.

Lawrence continued. “I should have made you give up searching this place.”

She looked at him, stunned.

“Those two are probably going to live together in the church. Elsa’s strength and cleverness will get her through the danger, and though I feel bad saying this, Evan will never be a merchant. But…what of us?”

Lawrence thought he heard a small voice, perhaps the sound of Holo inhaling sharply.

“I turned a profit in Kumersun. You learned more of your home. And you will probably learn still more here, and I am helping you. Of course”—here he spoke a bit louder, perceiving that Holo wanted to interrupt—“of course, I’m helping you because I want to. However…”

That which he had been able to avoid thinking about now confronted him.

Having gotten to this point, it would be a lie to say that the situation was impossible to explain.

But doing so would put more distance between them than slapping Holo’s hand aside or not trusting her could.

No matter how skillfully one evaded, all debts eventually came due.

“However…what will you do after we reach your home?”

Holo’s shadow on the wall became larger, perhaps because of the tail beneath her robe suddenly fluffing up.

But Holo herself seemed to shrink.

“I know not,” came her voice, also small.

Lawrence had asked the question he did not want to ask.

He did not want to ask it because he dreaded the answer.

“I’m sure you will not be satisfied with a mere glance at your home.”

Returning home after so many centuries gone—the words it’s been a long time hardly sufficed.

Lawrence didn’t have to ask what would happen once they arrived there.

He was filled with regret.

If he hadn’t asked the question, the distance between them might well have grown.

And yet—he wished he hadn’t asked.

If only Holo would look at him plainly and say, “There we shall say our farewells.”

Seeing her so troubled made him feel helpless.

“No, forget it. I am sorry. There is no point in speculation,” he said.

This was all pure speculation.

Lawrence’s own feelings were conflicted.

Although parting with Holo would bring with it the pain of loss, he felt he would be able to give her up.

When he took a loss in business, he would spend a few days feeling as though it was the end of the world, only to return to working at making money again as though nothing had happened.

But when the act of thinking rationally about the possibility itself filled him with sadness, what then?

He did not know.

“I am Holo the Wisewolf,” she murmured, staring at the flickering candle. “I am the Wisewolf of Yoitsu.”

Holo rested her chin on her knee, then slowly stood.

Her tail hung limp, as though it was mere decoration.

She looked first at the candle placed on the floor, then at Lawrence.

“I am Holo, the Wisewolf of Yoitsu,” she said, as though the sentence was an incantation. With a quick stride she came to stand directly beside him, then immediately sat down.

Before Lawrence had a chance to say anything, she was lying down on his lap.

“Have you any complaints?” Holo’s normal impudence was undeniably godlike.

But this impudence was entirely different.

“None whatsoever,” said Lawrence.

Neither tears nor anger nor laughter seemed to quite suit this delicate situation, which brimmed with tension.

The candle burned soundlessly.

Lawrence casually rested his hand on Holo’s shoulder as she lay in his lap.

“I’m going to sleep for a bit. Will you read in my place?”

Her face was hidden by her hair, and Lawrence could not see it.

But he knew full well when her teeth came down on his index finger.

“I shall,” he said.

It was like a test of courage—not unlike seeing how close one can bring the point of a knife to a kitten’s eye.

A bit of blood welled up from where his finger had been bitten.

He expected Holo would become truly angry unless he actually did some reading.

The only sound was the turning of pages.

Her evasion of the problem had been very forceful, but she had saved herself and Lawrence both.

She truly was a wisewolf.

On this count, Lawrence had no doubts.

Had the church been a monastery, it would have been time for the morning prayers thanking God for creating the new day.

Of course, it was far too early for the morning worship service.

The only sounds were of the turning pages and Holo’s soft breathing.

Lawrence couldn’t help but feel impressed at the fact that she’d fallen asleep. At the same time, he was a bit relieved that she had.

She had forcibly—so forcibly!—ended the conversation, demanding Lawrence neither say nor ask another thing.

Though she had not answered Lawrence’s question, her actions alone were enough.

After all, they made one thing abundantly clear: Holo did not wish to confront the problem any more than Lawrence did.

If she had changed the subject while the true answer to his question lay within her, Lawrence probably would have been angry. But as neither of them had that answer, he was grateful she had ended the conversation by force.

At the very least, this meant she did not have to come up with an answer right then and there.

Their travels were not over, and they had not arrived in Yoitsu yet.

It was the rare debt that was repaid in full before it came due, after all.

As he thought these things over, Lawrence put down the book he was reading and picked up another volume.

Father Franz had evidently been an intelligent fellow. Within the books, even the lineage of the various gods had been carefully organized, and a glance at the title of each chapter gave one a reasonable idea of its contents. This made the books easy to skim. Lawrence shuddered to think of how difficult this task would have been if Father Franz had simply collected tales at random as he heard them.

However, while flipping through the pages of book after book, Lawrence realized something.

In addition to the normal, common tales of snakes, frogs, and fish, there were many stories of mountain, lake, and tree gods. Likewise, there were tales of gods of thunder and rain, sun and moon and stars.

But stories of bird spirits and beast spirits—there were few of those.

In the pagan town of Kumersun, Diana had told many tales that concerned the bear spirit who destroyed Yoitsu. And near the Church city of Ruvinheigen, Lawrence himself had felt the unmistakable presence of a wolf-god not unlike Holo.

And Diana herself was a bird spirit larger than any human.

Given all this, the books should have been filled with beast legends. Yet Lawrence had found not one.

Did the books that they had brought up from the basement simply not happen to contain any such tales?

At that moment, Lawrence’s eye fell on a sentence written on a piece of parchment that was tucked into the book he had just opened.

“It is not my wish to regard the tale of the bear spirit in this book with any kind of special treatment.”

So far, every book Lawrence had looked through had simply been accounts of the tales Father Franz had heard, written in language as dry as any business contract. Having suddenly come upon this sentence in which he felt he could hear Father Franz’s own voice, he was momentarily stunned.

“Regarding the stories in the other books—there are many which differ in time and place, but which I believe nonetheless refer to the same spirit. However, this particular spirit is the only one whose stories I have organized so thoroughly.”

Lawrence wavered, trying to decide whether to wake Holo.

He was unable to turn his gaze away from the yellowed page. Father Franz’s handwriting was neat, but at the same time, it seemed somehow excited.

“Is the Pope aware of this? If I am correct, then the God we worship triumphed without a fight. If that is proof of His omnipotence, how could I possibly remain calm?”

It seemed as though he could hear Father Franz’s decisive pen strokes.

The passage concluded: “I do not wish to let bias cloud my view of all the tales. Yet I cannot help but wonder if the pagans of the northlands themselves did not realize the importance of the Moon-Hunting Bear. No, perhaps the very fact that I am writing this means that I am already biased. As I assembled these books, I felt strongly the existence of these spirits. If possible, I hope that one would judge not with the narrow mind of a worshipper of our God, but rather with the open heart of those whose love of God is like a zephyr in an open field. That is why I have ventured to leave this book in among all the others.”

As soon as Lawrence flipped the piece of parchment over, the book’s story began, much like any of the other books he had read.

Should he let Holo read it first? Or should he pretend not to have seen it?

The thought flitted through his mind for a moment, but it was too late for that now—and in any case, it would be a kind of betrayal.

He decided to wake Holo.

He closed the book, whereupon he could hear a strange sound.

Plip, plip, plip-plip came the small, dry sound.

“…Rain, eh?”

But as soon as he said it, he realized the raindrops were awfully large. Eventually he realized that the sound was of galloping hooves.

It was said that the sound of a galloping horse at night would draw a throng of demons.

When traveling by horse at night, one could never let it run.

Church follower and pagan alike believed this.

But its true meaning was common sense—a galloping horse at night never brought good tidings.

“Hey, wake up.” Lawrence closed the book and tapped Holo’s shoulder, listening carefully.

Judging by the sound of the hooves, there was a single horse, which entered the village square and came to an abrupt stop.

“Mmph…what is it?”

“I have two things to tell you.”

“Neither good, no doubt.”

“First, I found the book with stories of the Moon-Hunting Bear.”

Holo’s eyes widened in an instant, and she looked at the book near Lawrence’s side.

But she was not the type to have her whole attention stolen by a single thing.

Her wolf ears flicked smartly, and she looked back at the wall behind them. “Did something happen?”

“That seems very likely. There is nothing less welcome than the sound of a horse’s gallop at night.”

Lawrence took the book and handed it to Holo.

She took it, but he did not let go.

“I don’t know what you plan to do upon reading this, but whatever thoughts you have, I’d like you to tell me about them.”

Holo did not look up, but gazed evenly at the book. “Hmph,” she replied. “I suppose you could’ve easily hidden this book. Very well. I promise.”

Lawrence nodded as he stood. “I’ll go look outside,” he said, walking away.

Naturally, the church was dark and quiet, though not so dark that Lawrence’s eyes were useless.

Once he arrived in the living room, there was a bit of moonlight filtering in through the cracks of the window, which improved visibility.

He could see well enough to be able to instantly identify the figure that was creaking its way down the stairs as Elsa.

“I heard the sound of a galloping horse,” she said.

“Any notion of what is afoot?”

He expected she did, otherwise she would not have come immediately downstairs.

“More than I’d like.”

A village like Tereo was too small for the hooves to be from a town lookout coming to warn of a mercenary attack.

It probably had something to do with Enberch.

But had the crisis not already passed?

Elsa trotted over to the window and peeked out through the crack as she had no doubt done many times in the past.

Unsurprisingly, the horse seemed to have stopped in front of the village elder’s house.

“I only know what I have been able to piece together, but judging from the papers on your desk, Enberch should not be able to strike, should they?” said Lawrence.

“A merchant’s eyes are keen indeed. But yes. I believe so myself. However—”

“If you are going to tell me that the situation would be different if I’d betrayed you, I should tie you up immediately.”

Unintimidated, Elsa looked sharply at Lawrence.

She soon looked away.

“In any case, I am a traveler. If things go badly, my position becomes very dangerous. There are scores of tales of merchants who became wrapped up in local problems and lost everything.”

“So long as I am here, I will not allow anything like that to happen. But please, go and close up the cellar. If there is trouble with Enberch, the village elder will certainly come here.”

“And what of the reason we are here so late at night?”

Elsa’s cleverness was different than Holo’s. Somehow Lawrence felt an affinity with the girl. “…Bring a blanket to the sanctuary.”

“Agreed. My companion is a nun, after all. No argument, then?”

Though Lawrence had only wanted to confirm their cover story, Elsa did not reply.

For if she had, she would have been telling a lie.

She was a clergywoman through and through.

“Elder Sem has come out,” said Elsa.

“Understood.” Lawrence turned and went to Holo.

In times like these, Holo’s keen ears were quite useful.

She had already returned most of the books to the cellar and put her robes back on.

“Take that one book with you. We’ll hide it behind the altar,” said Lawrence.

Holo nodded, handing the remaining books one by one to Lawrence, who had descended halfway down the stairs to the cellar.

“This should be all of them,” she said.

“Then take the hallway opposite the living room. If you continue around the corner, it should take you to the entrance behind the altar. Head in there, and take the book—”

Holo ran off without waiting to hear the end of the sentence.

Lawrence climbed out of the cellar, replacing the pedestal and putting the statue of the Holy Mother back on top of it.

He was nervous for a moment, unable to find the keyhole in the floor, but he managed to locate it, and after locking up with the brass key Elsa had given him, he gathered up the blanket and went after Holo.

Church construction was very similar the world over.

Just as he had expected, the entrance was there, its doors open.

He trotted down the narrow path that he knew should lead to the altar, protecting the candle flame with his hand. Soon his view expanded.

A few slivers of moonlight slipped past a window on the second floor, enough that Lawrence felt he did not need the candle.

On the other side of the doors that faced the altar he could hear quiet voices.

He motioned with his eyes to Holo—hurry!

It could be problematic to explain the key if it was found on them, so he hid it behind the altar as well.

They sat on the floor’s only indentation, the place where Father Franz had probably said his prayers for so many years.

Lawrence extinguished the candle and wrapped himself and Holo up in the blanket.

It had been some time since he’d acted so very like a thief outside the door.

Once long ago in a harbor town, he had snuck into a trading company’s building with a friend to peek at the company’s order ledger.

At the time, he had not yet learned how to judge which goods were in demand. Thinking on the situation now, Lawrence realized it was a terrifying risk to take, although still much less so than what he was doing at this very moment.

After all, nothing he was doing in Tereo would make his coin purse any heavier.

The door opened, and Sem’s voice filled the room. “Still, as the village elder, I—”

Lawrence took a deep breath and looked up, dazed as though he had just woken from sleep.

“My apologies for disturbing your holy time in the church,” said Sem.

Behind him were Elsa and another villager wielding a wooden stave.

“Did something…happen?” Lawrence asked.

“I hope that as someone who has traveled much, you will understand. We may cause you some inconvenience for a time. Please bear with us.”

The villager wielding the staff took a step forward. Lawrence noted this and stood.

“I am a merchant who belongs to the Rowen Trade Guild. Many people in the guild’s house in Kumersun are aware that I have come to this village.”

The villager looked back at Sem, surprised.

If trouble was to arise with a trade guild, a village the size of Tereo could not hope to escape unscathed.

In terms of financial strength, a merchant guild was like a nation.

“Of course, Elder Sem, so long as you are taking appropriate actions as the representative of the village, then as a traveler I will certainly abide by them.”

“…I understand. But the reason I appear before you and your companion is not out of any malice, I assure you.”

“What has happened?”

The patter of more footsteps was heard; Evan had probably awoken.

Sem glanced in the direction of the footfalls, then looked back. He spoke slowly.

“Someone in Enberch has eaten the wheat of this village and died.”

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login