JANUARY 2, UNIFIED YEAR 1928, THE GENERAL STAFF OFFICE

Holed up inside the depths of the offices of the General Staff of the Empire, the whole world wants to know what was going on inside General Zettour’s head. “WHAT ARE GENERAL HANS VON ZETTOUR’S THOUGHTS THE WORLD WONDERS.”

But the thoughts the whole world so wishes to know are dominated by a single concern. One that he reveals bluntly in a meeting with the commander of the Salamander Kampfgruppe, soon to be redeployed in the east.

“Obviously, the Federation is coming. The question, however, is when.”

The implication of those words is painful. The initiative is in the Federation’s hands, which is a brutal statement on the Empire’s position.

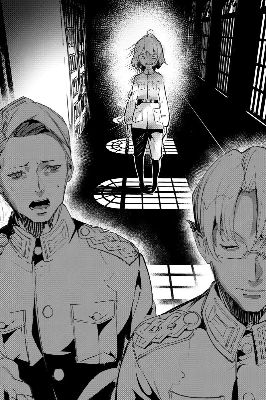

Whether they like it or not, Colonel Lergen, Colonel Uger, and Tanya understand the subtext of those words and have resigned themselves to the sad state of affairs. There is no wishful thinking here.

All three look as if they are nurturing headaches, with postures, each in their own fashion, that seem like they’re ready to groan.

Colonel Uger turns his eyes upward. He is a good man, the type to seek salvation. Colonel Lergen presses a hand against his stomach. He is one to face reality head-on. Tanya, meanwhile, closes her eyes and turns her head downward, obviously wishing to be anywhere but here.

In this moment, without making eye contact, all three know they are allies with a shared understanding of this distressing reality. But even if that wasn’t the case, it’d be unlikely that any of them would have been able to keep from reeling at General Zettour’s next words.

“Much of what we know of the Federation Army’s logistics is mixed with speculation. But extrapolating from the general situation, the possibility of a winter attack…can likely be ignored. Possibly.”

Zettour is an expert in logistics, recently back from a frontline tussle with the Federation. For a man such as he to use words like speculation, likely, and on top of that, possibly!

Of the three present, Colonel Lergen is highest in position. He raises his own question in response.

“Possibly is not quite the same thing as certain, though.”

Exactly. General Zettour chuckles softly and reaches for the cigar case left sitting atop his desk. As he is about to pull free a cigar, however, something catches his notice, and he softly puts the cigar back down.

“Your Excellency?”

Zettour waves his hand as if to indicate it is nothing, but his expression continues to harbor an unusual degree of hesitation. He begins to think out loud.

“In turning toward Ildoa, we’ve diverted a large amount of manpower and supplies in a very eye-catching way. In terms of simple calculation…if the Federation was planning a winter attack, they shouldn’t have been able to resist the temptation to do so as soon as we moved.”

Then General Zettour continues:

“On the other hand, perhaps deep down, they do have the guts to stake everything on a single wager…but I won in Ildoa. The Federation is careful. They will likely drag their feet until victory is certain.”

Without even meaning to, one might say. Tanya peers hard into General Zettour’s face.

“The only chance is now, in this moment. In spring or summer, once the mud season ends, the fighting will be fierce.”

It is a reasonable opinion. A rational, grounded, and common-sense analysis. Colonel Lergen and Colonel Uger remain silent, however. Something is strange.

“However, that does not mean there is no need to worry. To put it plainly, we are in a race against time. If they come now, we will be in trouble. There is no guarantee they will pass up this opportunity to strike at our weak flank. If they take until summer, we will be able to significantly bolster our defensive line, but still…”

Wait. I’m beginning to picture a terrifying prospect, but she endeavors to put that thought back on the shelf for the moment. It’s important to hear people out.

“Now then, we must draft a thorough essential plan of defense. Lieutenant Colonel Degurechaff, I’m sure you understand, but the sealed plans from when I was in the east are no more than rough notes. If our level of preparation was to be revealed, it would be an unmitigated disaster.”

Of course. Tanya nods.

While stationed in the east, General Zettour endeavored to shape strategy in a variety of ways and even formulated plans. Tanya herself had been involved in several of these efforts. General’s Zettour’s position at the time had been inspector. Thus…I am quite aware the sealed plans are not fully formed strategies but rather preliminary research.

What is he saying? That he wants us to prepare before this sorry state of affairs can be revealed to the enemy?

“This mud season will likely be a turning point. We still have just enough room to rest for a moment. However, the days ahead will be tough. Take this time to breathe in the fresh New Year’s air while you can.”

Good. I nod, waiting for him to continue. When nothing more comes, I decide to ask myself, eager to get down to brass tacks.

“The fate of the Empire is riding on this fight. Don’t you have anything more to say…?”

“Of course,” General Zettour says, his face showing distress.

“As long as I am here, the Empire will not lose, at least. I shall yet teach the Communists a lesson in reality that supersedes their ideology,” he says, adding no more.

The general’s face looks tired. The other staff officers understand that this conversation is now over.

The shrewd general, however, has been curiously evasive. The experience has been disconcerting. The three leave the room together, suddenly finding themselves without anything to say as they trudge along the General Staff Office halls together in silence.

Assuming there won’t be anything else, it seems like it’s time for all of us to drift off in our own directions. I’m thinking about finishing up my remaining work and leaving the office quickly for the day, when Colonel Lergen steps in to put the kibosh on my budding sense of freedom.

“Colonel Degurechaff, perhaps a cigar? I have some excellent stock from Ildoa,” he says frankly, sounding like a person suggesting a nightcap after a party has ended.

As socialization goes, it is almost a boilerplate invitation. But Tanya is underage. Care for a cigar, indeed!

In fact, it’s technically a crime. Maybe too much war has caused the good colonel to forget common sense.

Of all the… I open my mouth to remonstrate Lergen for his invitation, when I notice Colonel Uger stepping forward and promptly close my mouth.

What luck! A lieutenant colonel refusing an invitation from a colonel could cause offense, but if someone could rebuke the colonel in Tanya’s place? I feel a wave of gratitude for Colonel Uger’s attentiveness. How masterful!

“Colonel Lergen, please consider who it is you’re speaking to. It is Colonel Degurechaff.”

Yes, exactly. I nod mentally in response. Perhaps Colonel Lergen has something he wishes to discuss, but he should keep Tanya’s physical age in mind.

“The smoke would be too hard on the lungs for an aerial magic officer such as Colonel Degurechaff. Do you want her to choke up there in the sky? What were you thinking…?”

“Oh? It would only be a puff or two. But well… Ah, is it the secondhand smoke? Maybe it would be too much.”

Colonel Lergen and Colonel Uger are supposed to be the best of their generation, possessed, you could say, of a highly progressive spirit and—both as members of their organization and as individuals—relatively free from the conventions of the time. At the moment, however, they seem to have entirely missed the mark.

Perhaps because they lack the diversity of experience Tanya enjoys. Seeing as the conversation isn’t going anywhere, I grudgingly open my mouth.

“Excuse me, gentlemen? You seem to have forgotten that I am underage. Underage smoking is prohibited by law, and military law provides no exception.”

Smoking and drinking by minors is not allowed. It’s a simple enough concept, with no room for discussion. And yet.

These two staff officers who are allowed to pass freely through the inner chambers of the office on the merit of their talents—high-ranking soldiers reporting directly to General Zettour himself—suddenly stiffen in shock. They look as if they have just been struck by lightning, and it takes them a good moment to get their expressions under control.

If one was to attempt to describe the looks on their faces, one might say that Colonel Lergen’s expression is one of shock, whereas Colonel Uger’s is one of amazement. They seem to have realized that interacting only with their own closed circles has left their sense of what is normal somewhat skewed.

Still, though, those faces! I can’t help but feel a little exasperated.

They would have made for an amusing photograph. The way people would laugh if they could see them.

“That’s right, the lieutenant colonel… You are…the lieutenant colonel, you are the lieutenant colonel…”

Colonel Lergen appears to be rebooting. As far as I can tell, he is trying to say that I am a minor, but he only manages to repeatedly mumble the words lieutenant colonel, which are not, in fact, a synonym for underage. When all one knows is the military, however, they begin to interpret everything in terms of rank.

“Yes, if I was to smoke a cigar, we would all be reprimanded.”

Underage drinking and smoking is a very serious problem. It impedes healthy physical and mental growth and causes damage to society as a whole. Although, if anyone was to ask Tanya, she might point out that it is war that is most harmful to the health.

“Forgive me, Colonel Degurechaff. It’s not just that we were in war college together. You’ve also become such a rock lately that I can’t help but think of you as being older than you are.”

“Thank you for those flattering words, Colonel Uger. Although, the truth is, I don’t seem to be growing very much.”

An awkward silence begins to descend, but Colonel Lergen, ever the strategist, seems to have pulled himself back together again. He speaks in an obvious attempt to shift gears.

“Well then, Colonel…how about some tea?”

In that case, of course Tanya gladly accepts.

I would rather not be dragged along into this prolonged after-party, but rubbing shoulders with a hands-on man like Lergen might prove beneficial. The last thing I want is to wind up on the front lines, isolated and alone, because I overlooked a helpful connection.

Without further ado, Colonel Lergen claims one of the General Staff Office rooms. Colonel Uger casually has the orderlies bring in a collection of precious tea cakes, in line with the fashion of the times—an expression of his privilege as an elite, with influence even in the inner chambers of power. As someone who works mostly in the field, I’m feeling rather envious as the tea is soon laid out.

As I stand by and watch, however, my nose picks up on something curious. Despite recent circumstances, the General Staff Office’s reputation for legendarily atrocious food does not seem to apply to this current spread.

As Colonel Lergen urges us to dig in, he seems to notice the expression on Tanya’s face.

“Decent refreshments for a change, aren’t they? I thought I’d have an experienced orderly prepare it. Though, perhaps coffee would have done as well. Not everything must come from Ildoa, after all.”

Hmm? I raise my head in response.

“I’m sorry, but this wasn’t plundered, was it?”

“These are my own personal provisions, procured by legitimate means. I say this in front of Colonel Uger, but the Service Corps is very strict when it comes to embezzling spoils of war. As they should be. I bought these goods myself.”

Personal provisions. I bring the cup of tea to my lips dubiously. It is extremely mellow. Truly, a stray visitor from the world of aroma, color, and flavor.

I am no expert and can only describe it as good, though even an amateur could immediately tell the difference between this and some muddy imitation.

How did he get his hands on something like this in the middle of total war, here in the Empire, where tea is not produced?

“The palace’s New Year’s party was just yesterday. I purchased some of the leftover share from the wife of one of the officials.”

“The connections one enjoys when one works for the interior. But where did it originally come from?”

Constantly stuck on the front lines, I cluck my tongue in jealousy of those who get to work in the rear.

“Are you interested in the logistics, Colonel? Honestly, these fine wares were likely carefully shuttled in by various embassy employees remaining in the capital, by way of their diplomatic bags.”

“Well then, if Colonel Lergen doesn’t mind, let us enjoy this delicious meal.”

And it is delicious. Limpid and luxurious, the cup of tea brims with delicate aromas, and the balance of acidity and body is transporting. There is an inimitable depth to the flavor.

I sip my tea, enjoying the elegance. As I sample one of the cakes, I turn toward Colonel Lergen, remembering something.

“Yes? Was there something you wished to speak about?”

“Well…if you are in the mood for conversation…”

“You were kind enough to invite me to tea, Colonel, so I will sit here politely and sip my tea, but is that really the only thing you had in mind?”

Colonel Uger stares at Colonel Lergen as if to suggest this is his own fault for managing the invitation so poorly. Captain Lergen slumps his shoulders and gets down to business.

“It is about General Zettour.”

“The general? You mean you’ve gathered us here to gossip about him in secret?” I ask, pulling back with a somewhat wary expression on my face. In response, Lergen hastily waves his hand as if to suggest he means nothing so unsightly.

“General Zettour has my full support—do not mistake me.”

“Please, Colonel Degurechaff, I am asking you as well. Please hear us out.”

“You as well, Colonel Uger? Fine, what is it you have to say?”

With a quiet grunt, Lergen crosses his arms and furrows his brow slightly, as if carefully choosing his words.

“It is…difficult to put into words. But at the moment, General Zettour is— How can I put it? He is not frightening. And the fact that he is not frightening is extraordinarily terrifying.”

That fact that General Zettour is not frightening is in itself frightening? As I decipher Lergen’s meaning, I quickly turn my eyes toward his. The colonel’s eyes appear normal. Completely sane.

“I know, it sounds strange. Our deputy director was doing excellent in Ildoa just the other day. He came, he saw, he conquered. I remember.”

“I saw him when he arrived at the front as well. I’ll never forget the chill that ran down my spine at the moment of victory. But even with that memory, I cannot find anything fearsome about the general now.”

“Is the difference that pronounced?”

“Yes,” Colonel Lergen says, the conviction evident in each word he speaks.

“In the east, there is a clear difference. The general is simply ordinary.”

Uger nods in understanding, although the two are usually reticent to speak ill of others.

“I’m sorry, Colonel Uger, but what exactly do you mean?”

“When standing in General Zettour’s presence…I would usually find myself reflexively trying to stand up taller. Perhaps it is different for one of your mettle, Colonel, but it is impossible for us ordinary people not to tense up in his presence. At the moment, however, the general’s fearsome aspect seems to be growing somewhat—how to put it?—thin…”

Lergen leans forward in total agreement and begins speaking again.

“To put it plainly, something seems to be missing, something difficult to describe. Whatever magnetism it is that makes the general himself.”

I think back on our earlier interaction. Yes, it’s true. While Zettour was delivering his thoughts on the east, something was lacking. What might be called his aura. Ultimately, I shake my head.

“Yes, I suppose there was something worn out or scattered about him…but everybody hesitates at times, don’t they?”

That aside, I shake my head in thought. For better or for worse, the two colonels have ample opportunity to be in close contact with Zettour and know him best. If even Tanya sensed it vaguely…

“We cannot say, without a shadow of a doubt, that there is no cause to worry…”

“You saw it as well, Colonel?”

“Yes. What do you think, Colonel Uger? Perhaps an issue with General Zettour’s health…?”

“He has been tired. Especially after yesterday’s banquet.”

“Has he?”

“Yes. After he returned, his complexion was quite poor.”

Colonel Uger’s words only further strengthen my misgivings.

“I’m sorry, but may I ask something?”

Uger turns toward her questioningly.

“Was this palace banquet, or whatever it was, really such a draining affair?”

Unfortunately, I have no experience with such things. I’m deeply unfamiliar with the connections between the army and the court. At times like this, I can’t help but be reminded of the difference between my current situation and the career path I failed to walk.

For better or worse, however, Colonel Uger is decidedly a career soldier and, as one of the inner elite, is well-versed in such events. He seems to be considering how to answer Tanya’s offhand question in a way that can truly convey what these parties are like. After a moment, he seems prepared.

“Yes, Colonel, truly draining indeed,” he explains carefully, beginning in classic detail with his thesis statement before moving on to supporting details. “Events such as this party are truly exhausting. They leave your shoulders stiff, and the difference in atmosphere and mentality is even more shocking than the difference between the front lines and the rear. Even when one knows what is coming, they are difficult to endure.”

Colonel Uger offers his own personal opinion as well.

“This is only my subjective view, but…based on my experience providing support, I imagine even commanding a great battle might be significantly less stressful.”

“Plus, he is far too busy with his duties to begin with,” Colonel Uger adds, a weighty expression on his face.

“Honestly, it’s ridiculous. He is serving as deputy director of both operations and the service corps. And for all intents and purposes, he is practically chief of staff as well. He is filling three roles alone, and he even went off to Ildoa to bolster morale and oversee the troops. On top of everything else, he was forced to act as the face of the military at the New Year’s banquet. How much can be asked of one person?”

I grimace in response. This sounds like an example of organizational failure being temporarily covered for by the competency of on-the-ground administration. When administrators with such a wide range of abilities happen to be present, the fact that they can handle such things allows the ridiculous to soon become the norm…and fortunately or not, such people tend not to rest even when they know doing so is necessary.

What comes next is simple. When humans do not rest, they break down. And when a person goes beyond their expiration date, there is only one possible outcome. Once the capable administrator collapses, with so much still on his plate, there is sure to be a mess. I frown and sigh.

“Priorities need to be kept straight. There is only one General Zettour. And if there is only one, then his strengths must be focused where they belong: on administration. The entire game should not be placed on a single player’s back, regardless of how skilled they are.”

I believe what I’m saying is fairly obvious, but I’m met by a dubious expression from Colonel Lergen. I’m practically scowling internally, wondering if I’ve misunderstood something. But what the colonel says next causes my lips to twitch in displeasure.

“Oh, that’s right. Colonel Degurechaff, you are so abundantly capable that they never assigned you to work as a strategist back here at the General Staff Office.”

Well! Wouldn’t we all like to be inner elite, sitting back here at the General Staff Office, like His Highness Colonel Lergen? His magnanimous tone of voice only serves to further prickle my nerves. Though, of course, I know that the colonel didn’t mean anything by it.

Colonel Lergen is one of the central staff officers, favored sons of the organization—in other words, a man of sterling career. As someone whose own career path has not taken me to the inner chambers, I understand the colonel’s words are just a natural reflection of his position. But whether I like it or not, I can feel it. A barrier, like an invisible ceiling, above my head!

For Colonel Lergen and Colonel Uger alike, even their regimental commands are really just a formality. They are essentially fixed in place. Although they do occasionally find themselves venturing outside, this is just a part of the distinguished leadership’s efforts to better grasp conditions on the ground. Their permanent place of residence is still the heart of the center.

In the end, their upbringings are simply too different from Tanya’s.

When we were together at war college, it seemed like Colonel Uger would wind up becoming a serious rival for promotion. Somehow or other, though, my career led me away from the limelight. That is what was so confounding about it.

Not that I have any bizarre ideas about dying along with the Empire. There is no point getting overly invested in a career at a workplace that Tanya will transfer out of someday.

Of course, Tanya is a person of civilization, good, peaceful, and free. But in the end, it is impossible to ignore the Imperial Army’s personnel assessment—their assessment of her marketplace value. In an odd reversal, it is faith in the market that has left Tanya conflicted.

But that can’t last forever.

As I turn my attention back to the discussion at hand, Colonel Lergen finally reveals what it is he’s been thinking.

“The General Staff has traditionally kept to an ethos of small but elite. The office’s reputation is great, but inversely, the number of actual strategists present is limited.”

“Hmm, so…what you are saying is the system has limits? Personnel fatigue?

I begin to say “That makes sense,” but stop short. Based on the look on Colonel Lergen’s face, I realize that I have once again misunderstood.

“No, no, that’s not it, Colonel.”

Two nos! I close my mouth, realizing I really missed something fundamental. Now is the time to wait for an explanation.

“When it comes to the Imperial Army, there are so few strategists to begin with that administrative positions are generally not necessary. For deputy directors and so forth, it’s standard for them to be enormously talented. As long as they can handle administrative tasks in their free time, that’s considered more than enough.”

“What? So then how are operations actually planned and developed…?”

“It is an idealistic notion, but when it comes to plans, a broad outline is enough. Similar to a train diagram. Elaborate and complex, but at its roots, still only a sketch.”

“Colonel, does that mean that…these so-called plans, strictly speaking, are meaningless on the actual battlefield? That we are in constant need of better blueprints?” I venture, urging him to get to the point with my eyes. This is beginning to feel like some sort of verbal examination back at academy, and I’m growing tired of the back-and-forth.

“True, there is some friction with reality. No matter how far technology comes or how well trained our soldiers, there will always unfortunately be fog of war. Even assuming a plan is perfect at the time of drafting, perfect implementation is impossible.”

The idea of a perfect plan, itself, is armchair idealism.

However, that is precisely what makes advance conjecture and planning so important. By considering the possibilities and how they might unfold, one can make the necessary preparations. I’ve had the importance of planning drilled into me at both military academy and war college, so I can’t help but remain skeptical.

“There is no such thing as ‘according to plan.’ The battlefield is a cauldron of uncertainty.”

“And yet you still feel that plans are necessary?”

“As you should well know,” I say, smiling in reply to Lergen’s question. “Plans are futile, yes. A plan provided today and executed with conviction is of much more value than a perfect plan that won’t be ready until next week. But that statement only holds true within the larger framework of planning. Even if only to compare the worst and best and decide which to choose, there is meaning to planning in advance. During officer training, that fact was drilled into our heads over and over again.”

“That is correct. But I would like to add the addendum that in reality, combat levels must often be compared on the front.”

“Colonel Degurechaff, if I could add to what Colonel Lergen has said, you have often carried out operations while in direct communication with General Zettour, have you not? That may be an exceptional situation, but it is not rare for the Imperial Army to devise its strategies around the axis of such exceptions. Our plans are highly dependent on the capability of individuals. Though, it is an understandable misconception, of course,” he says.

I involuntarily blink at that.

“Even if the strategies of the General Staff are like works of art, so to speak, created by individual craftsmen, and not the creations of an organization…”

“You misunderstand. The operational-planning capabilities of the General Staff are not so simple at the individual level. But do you see, Colonel? We are always operating according to how things ought to be.”

In an elegant gesture, Lergen touches the frames of his glasses, his eyes taking on a faraway look.

“Recall the Empire’s largest offensives. Operation Revolving Door. Operation Iron Hammer.”

Against the François Republic, and against the Federation.

“Even when choosing the wrong opponents,” Colonel Lergen says, getting to the point, “our army has traditionally not valued having a plan B when carrying out these types of attacks. Or perhaps it would be better to say, it’s less that we haven’t valued having a plan B, and more that we haven’t had the capacity for it.”

“Not just that those on the ground haven’t been informed…?”

“During Operation Andromeda, that shortcoming almost led to our army dying in vain.”

It was a massive setback in their war against the Federation. Perhaps even a fatal failure. The hardships brought about by that strategy are all too familiar. I can only nod in understanding.

So preparation is clearly lacking when it comes to having a plan B. Or perhaps, because they can’t afford to fail in the first place, no one has given much thought to what to do when failure does occur. I’m beginning to see where the issue lies.

“That is the terrible side of being dependent on victory. If you cannot afford to fail, you may begin to devise strategies under the assumption that you will not fail and simply lean fully in. In a way, it is understandable. I see. So that is why objectives given on the ground are always so simple yet excessive,” I say in conclusion.

Come to think of it, although the expressed intentions were always understandable, when it came to strategic objectives, we were only ever given one aggressive option on the ground: plan A. My comment, however, causes a sour expression to appear on Lergen’s face.

“True, but are you sure that is not just your frontline syndrome speaking?”

“Colonel Lergen, that is too harsh,” Colonel Uger warns.

Lergen shakes his head in denial. “Listen,” he says, turning this way and speaking slowly and carefully. “Commanders in our army pick out the meaning in our orders and then act freely and appropriately to achieve goals. We have come to value the discretion of individual commanders in fulfilling the orders they are given.”

“Well, it is the commanders who must execute the mission. Is this not a good system?”

“It is not bad, but our army has become overly specialized. To put it a different way, we do not know any other way to give orders. And we rely on the discretion of those implementing the plans to figure out the finer details.”

“Is that a problem? The system seems to be functioning perfectly fine.”

If functioning as envisioned, with individual commanders at all levels striving to make the most appropriate decisions without needing to rely on constant communication with and oversight from superiors, such a system would be unbeatable. Creating the necessary organizational culture would be difficult, but once created, it’d be truly powerful. But the Empire succeeded in creating and implementing exactly such a system. So then where is the problem?

I find my own job much easier to handle due to Visha’s ability to understand my intentions. Likewise, I’m more than pleased to leave things to Major Weiss. But what if…? And before I can entertain those doubts, the two colonels have already begun to explain.

“Strategically, our defensive plans have always been built around interior line strategies. We have specialized in making the best choices within that framework.”

“Yes, when it comes to interior lines, we are a fearsome foe to behold…,” Uger says, nodding in agreement with Lergen. It takes me a moment longer, however, to comprehend.

Why are they mentioning interior line strategies?

Researching countless military topographies, keeping precise and flexible diagrams, a doctrine of delegating practically all tactical decision-making… As I think about all this, I finally begin to notice the problem.

“With interior line strategies, in an environment dedicated to counterattacking, every last soldier is highly familiar with the territory, and there is no real need to clarify the order of priority for what areas should be protected.”

Lergen grimaces in response as I realize what he’s been saying.

“Exactly, Colonel. Our army is strongest when we are fighting in our own backyard. And we have spent many years studying only that type of fighting. It is the fundamental character of our army, even when conquering enemy territory.”

“If I could add to what Colonel Lergen has said, when it comes to delegating defensive plans to ground forces, we have not gone far enough in instilling a unified approach toward how to act when not fighting in our own backyard. Do you understand?” Uger asks.

My brain finally grasps what it is the colonels are leaving unsaid. The root of the problem is their organizational culture. In this regard, the Imperial Army’s culture, while a type of strength, is also a type of weakness.

The Empire’s approach to operational command is based around transmitting targets to commanders. To put it in extreme terms, the Empire’s approach to orders is akin to saying, We are going to provide our guests with dinner, so acquire enough steaks for four people. In the extreme example, what kind of steaks per se, and how to acquire them, is up to the commander to decide. They could buy their own preferred cut and cook it to their liking. Or if they were worried the flavor would be underwhelming, they could telephone a steakhouse and have steaks delivered. They could even place it all into the hands of a talented chef who just happens to live next door. Everything is permitted.

On the other hand, if the only option is game meat, then the commander’s only choice would be to take the classic approach and go hunting.

Even an outsider can likely understand that much. But that is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how the Empire does things. The byword of necessity means that commanders of all rank are expected to go above and beyond as a matter of course.

Using the example of steaks, a commander might interpret those orders to mean, The fundamental requirement is to provide dinner, but a different menu would serve perfectly well for vegetarian guests, and so, rather than steaks, they’d provide a vegetarian meal more to the guests’ liking. This would qualify as a clear-cut example of observing the intention of the order, even while not taking any of the directions literally for the particulars.

Within the Empire’s organizational culture, this is the fundamental role expected of commanders at all levels.

But what about by-the-book orders, with oversight of everything down to the smallest details? The basic framework of the order, Provide steaks for four people, might be the same. However, the finer points would be clarified in the manual, with a scheme to ensure that the same results could be achieved regardless of who’s carrying the orders out. For instance—Provide steaks for four people from Steakhouse A. All steaks must be cooked medium-rare. If catering from Steakhouse A is not available, instead procure 150 grams of red meat per person from Butcher B, at a budget of up to 3,000 yen per person; cook steaks to medium in accordance with the standard manual for steak preparation; arrange and serve in a simplified fashion as appropriate to wartime conditions. If 600 grams of said meat cannot be obtained solely from Butcher B, Hamburg steaks may be permitted (but only if command is informed and prior consent is obtained). If preparing Hamburg steaks, the ratio of ground meat must meet or exceed military standards. If obtaining the appropriate meat from a butcher proves difficult, report back immediately.

Under this approach, the issue would be whether this litany of eventualities could account for all circumstances. For instance, if the existence of vegetarians has been accounted for, then a clause such as If vegetarians are present among the guests, provide suitable vegetarian meals can be included in advance, allowing the commander to make such arrangements without delay.

But if not?

The order is to provide steaks. And if, unfortunately, Steakhouse A is able to provide catering for four? Well then, the order can be fulfilled. The commander can arrange steaks for four people.

Naturally, upon realizing that one of the guests is a vegetarian, an obvious issue will arise. But the order given leaves no room for interpretation. It calls for steaks from Steakhouse A. In that moment, the commander on the ground will be left in a dilemma. Follow orders, or commit insubordination?

These are the obvious differences between the Empire’s approach and a by-the-book approach to giving orders. At a glance, the Empire’s way of doing things seems superior. An organization like the Empire, composed of officers who can think for themselves, obviously seems preferable at first glance. A place where people can do what needs to be done, appropriately and without constant interference from higher-ups over every little thing. It would seem to be the ideal workplace.

The reality, however, is that the latter type of organization is far more robust. And why is that? The answer is simple. Because the latter system allows anyone to fulfill orders to a reasonable degree.

The Empire’s style relies on an unspoken agreement among commanders, with results and on-site adjustment evidently relying on every person understanding the role they need to play for the greater goal.

Imagine another unit has been tasked with providing a wine that pairs well with the steak. If the person responsible for providing the steaks has suddenly, in their judgment, decided to switch to a vegetarian menu instead, then ideally, under the Empire’s approach, once the person has informed others of the change, the one in charge of providing the wine would, of their own accord, pay special attention to the fining technique used and choose wines that don’t use any animal products.

For instance, in response to requests for “an X-year bottle of A,” they might decide, Naturally, I will secure Wine A, but even without being told to do so, I will also secure a wine suitable for vegans. The servers and valets would then take similar care. All without anyone needing to give directions. As long as information is shared, each person will be able to make an appropriate judgment.

This is what allows the Imperial Army to turn quickly on a dime… They are highly adaptable to changes in circumstance and, when necessary, can even do the unthinkable and ignore finalized plans. The Empire’s strategic planning takes such flexibility for granted.

However, without mutual understanding and confidence of one another and of how each unit will behave under the circumstances, such flexibility is impossible.

In other words, what would such an arrangement look like when they are placed outside their own backyard? Considered in that light…I tremble. With close acquaintances such as Lergen and Uger, it would be one thing, but if told to cooperate with a colonel I know almost nothing about? How am I supposed to figure out how this unknown colonel might act during large-scale maneuvers in enemy territory?

With an interior lines strategy, it might still be doable. Imperial officers have been trained on what to do in almost every eventuality, and I can trust that the others have all undergone identical training. But with this current chaos…?

“Colonel Lergen, that would mean that when it comes to defense plans in the east…”

“It barely needs saying, but yes, we have no shared footing.”

Sighs fill the room. In that moment, I understand, whether I like it or not. From a different perspective, the Empire’s style of giving orders, which seemed so impressive before, is not suited for total war, where the strain on human resources is too great.

In an organization where all the employees are lifers and have all gotten to know one another well. Where everyone knows how to approach their work, and not only voluntarily throws themselves into their duties but also continues to proactively self-invest. Where long periods of time are spent training new people. Then yes, that would be fine.

An organizational structure such as that, where everyone comes together as one, obviously has its strengths and clear advantages. But as I’ve said before, war is cruel, and it is always hungry for more human capital.

To take drafted soldiers—who have been made officers only by virtue of graduating from the war college but who are still outsiders and not career men—and incorporate them into such a structure, and to ensure they behave appropriately…

Even someone like Tanya, whose watchword is training, is forced to admit it would be impossible.

Once upon a time, the Empire never dreamed of resorting to part-timers, but it has found itself forced to turn to such soldiers as a last-ditch effort, due to the demands of rapid expansion. Although they assumed they would see the same level of ability and results from these part-timers as from full-time staff, instead, they have found themselves with a limited number of full-time staff cleaning up after their part-time staff, while company conditions grow increasingly worse.

Throwing large volumes of talented staff at a problem is a decent enough solution, but real strength lies in avoiding any such dependency on any individual through talented management. But if a company can’t do that? I’m beginning to realize why General Zettour emerged onto the front lines so many times.

“So that was why he showed up directly, despite his age.”

Their current organization is one that requires management to fully commit as players on the field! Organization? What a laugh! Scorn drips from my lips.

“So in order to keep objectives clear and simple and prevent confusion among soldiers, administration needs to be sent all the way to the front…? That is awful. That explains all the trouble my troops experienced as guards.”

“You’re complaining about when I served as the temporary head of the 8th Panzer Division, I assume? I, too, have opinions on that matter.”

“For my part, I found it somewhat enjoyable,” Uger says, although his smile seems rather bitter. “I come from the Railroad Department, where we’re generally in the rear, but it’s not just diagrams. Most of the people who work on operations have been plucked for duty out in the field managing the railways. It’s quite rough.

“So you see…,” he says, casually continuing. “We’re in better shape compared with other departments when it comes to losing men, but even the railway builders, who are supposed to be all-important, have encountered the same problems. How much room is left for unspoken agreement at this point? Other departments, I imagine, are in similarly rough shape. Last-ditch efforts to replenish ranks aside.”

“Well, when it comes to magic officers, recruitment is almost nonexistent…”

I come very close to complaining about how overworked we are and how rotations have gone to shit, when Lergen intercedes:

“You are unhappy about the lack of new troops. But in many other units, their magic battalions have been reorganized into two companies right now, with one of those two companies chronically short on manpower. The entire army is in the same state. You’ll just have to make ends meet.”

“The armor divisions in Ildoa seemed strong enough.”

“Yes,” Lergen says, puffing his cheeks out nostalgically at the mention of Ildoa. In the next moment, however, he shakes his head from side to side.

“Ildoa was an exception. You should assume panzer units are completely barren. Even in exceptional divisions, replenishment of tank regiments is, at best, around sixty percent. I’ll say this up front, but any company with a new-model tank should consider itself extremely lucky. In many cases, the priority is simply on replacing equipment. The prevalence of old models is bad enough, but the drop in skill levels among tank operators is abysmal.”

Terribly threadbare. Lergen and Uger likely mean what they said. But for me, someone who is familiar with another world’s history, 60 percent seems far better than anything we could have hoped for. Although, that, of course, is only by comparison.

“Nothing in the cupboards, and nothing in the pantry. It seems the Imperial Army is now just as poor as everyone else,” I grumble. I turn toward the ceiling and sigh lightly. “I was under the mistaken assumption that the Imperial Army is blessed when it comes to manpower. I would have never guessed we were already beyond numerical problems and are dealing with quality issues as well… Although, there is a balance to be had with infantry. Maybe I have overestimated the importance of mages. Not that I mean to play favorites.”

At this, Lergen waves a hand, likely to assuage my concerns.

“We may be able to produce orbs in factory, but it’s not as if we can exactly mass-produce mages.”

“True,” I say, agreeing.

“It takes about ten years of training. Even if we began mass production now, we know they wouldn’t be useful by summer, let alone by next month.”

“Usually, it takes twenty years. Even speeding up the process, it would take sixteen.”

“I wonder.”

“Colonel Degurechaff, Colonel Lergen is once again correct in this regard.”

With a sigh, I momentarily lay down my arms.

Lergen seems to say So you see… before speaking up again. “Either way, that is exactly why I want to get an exceptional unit back into the east as quickly as possible. In order to alleviate the burden on General Zettour.”

“I understand. Is that all you wished to speak about today?”

“No, I am only getting to the important part. The truth is that I wish to investigate a range of questions related to General Zettour’s pullout from the east.”

“A range of questions?”

“Yes,” Colonel Lergen sighs, as if nurturing a headache. “The 203rd Aerial Mage Battalion reports directly to the General Staff, as does the Salamander Kampfgruppe. A piece on the board that, until now, has been managed directly by General Zettour. When General Zettour was flexing his might in the east, this was not an issue; however…”

Ahh, now I finally understand.

“…while General Zettour is in the capital as an administrator, handling Eastern Command, which is essentially in its own jurisdiction, can be a challenge for us.”

Territory and authority. These are always thorny issues.

“When it comes to Eastern Command, General Zettour tends to have a short temper. Well, we’re giving it our best with General Johan von Laudon, a strict fellow whom General Zettour once called dedicated. But there are plans to switch out senior staff in the future.”

“You mean…”

A cull? I digest what he has said. Lergen smiles uncomfortably and nods.

“The truth probably isn’t far from what you’re imagining. It will likely take some time for General Zettour to muscle his way through. But to improve operational efficiency, Colonel Uger will intercede directly in a variety of ways to ensure thing go smoothly when transporting Salamander back to the east.”

“Leave it to me, Colonel Degurechaff. I’ve already prepared transport. I am calling it an experiment, but I have arrangements in place that should allow a single Kampfgruppe to be deployed to the east in about three days’ time.”

A promise of aid, from specialists in the rear. Of course, I realize, this must have been what they brought her here to discuss. As I’m thinking this, however, I notice that both colonels are wearing somewhat tense expressions on their face.

“I’m sorry, Colonel. Is there something else?”

Finally, Colonel Lergen’s expression seems to say. He begins talking once more.

“This is what I really wished to speak to you about… The real effect of General Zettour’s removal from the chain of command in the east is highly unknown. Thus, if you find your unit seems to be withering on the vine…if necessary, you may make use of my name.”

So that’s what this is all about. The real purpose of this nightcap is a thoroughly off-the-books discussion. I ask my own question in response. One that shows I understand.

“As Lergen Kampfgruppe, you mean?”

The answer I receive, however, is unexpected. Today is turning out to be just full of surprises.

“As Colonel Lergen, if necessary. And ex post facto when required. In terms of logistics, you may also impose on Colonel Uger using the General Staff’s name. We should be able to more or less square accounts in that regard.”

“Unless I’ve misunderstood you, you are giving me carte blanche to launder your name and interfere directly in logistics.”

“Your ears appear to be working perfectly, Colonel. The proper authority, to the proper person, in the proper dimensions. Though honestly, I do find the prospect of writing you a blank check somewhat terrifying.”

Can it be? Is this real?

I turn a questioning look Lergen’s way but am met with an expression of apparent resolve. The confidence surfacing in Lergen’s face, however, only lasts a moment.

“Just don’t go burning Moskva again! Or well, maybe it would be better if you did. I don’t know. At the very least, try to mention it to me first?”

“Don’t count on it. Not in this half century, at least.”

My response is greeted with laughter. Strange, he must have thought I was joking. I’m not sure what is supposed to be so funny about it, though. Maybe it can be chalked up to a difference in culture and world views.

Sometimes, people don’t see eye to eye, but that is just a part of being human.

“I feel relieved, Colonel Degurechaff. Thank you. However, I imagine you may run into troubles even with my name in your keeping. Direct communication would be proper, of course, but I will authorize contact by messenger on this end—”

“Excuse me for interrupting, Colonel Lergen, but might my lines of communication as a railroad man be acceptable?” Colonel Uger says, with an expression on his face that suggests he is worried he is being too forward. Colonel Lergen, however, sighs and shakes his head.

“We’re always hungry for information from the ground. In particular, accurate information. As a clear deviation, there will be trouble…but internally, only a direct line to General Zettour can be secured. First and foremost, we want to get information out to General Zettour, out on the ground, as quickly as possible. All the more so, with the situation in the east so dangerous.”

“Understood,” I say, before continuing. “To be honest, however, isn’t it a bit early to redeploy to the east? Salamander Kampfgruppe is accustomed to being overused, but we’ve already reached the point where I am getting notices from Personnel cautioning me to not use leave.”

“When was this?”

“Just now, I picked one up in the General Staff mail room.”

“Do you have it on you now?”

“Yes, here it is.”

Lergen, most inner of the inner elite, takes the outstretched piece of paper and begins scribbling on it.

“Full exemption granted due to operational necessity. By order of the Service Corps of the General Staff Office.

“There you go,” he says, as he begins to hand the notice back to me. His hand, however, freezes partway, and he passes the paper to Uger instead.

“Colonel Uger, would you handle this?”

“Yes. I shall explain as well. Worry not, Colonel Degurechaff, you can count on me.”

“You both have my gratitude, I’m sure.”

Although, if you really want to help, how about a little time off instead?! At least, that’s what I think in the back of my mind.

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login