Chapter 11: Their Juniors

The busy days went quickly by, and soon it was early summer. Maomao found herself doing her work in an increasingly clinging, humid atmosphere.

At the moment, she was completely absorbed in taking care of the towering pile of laundry that had accumulated.

“The apprentice doctors...have time to spare... They could at least...do some washing!” she groused as she stamped, barefoot, in a bucket full of water and laundry. She’d been gobsmacked when she’d seen the mountain of physicians’ uniforms, as well as bandages fouled with blood and fat. She wished there was something they could do about how fast the laundry piled up around here.

Yao and En’en, battling along beside her, felt the same way. Lately, Maomao had been assigned to a separate medical office from the two of them, but for the purposes of doing the wash, they’d decided to get together at a well where it was easy to handle the laundry.

“Maomao, you’re getting water everywhere,” said Yao, who had taken a splash. She glowered at Maomao.

“Sorry. This is just the fastest way to wash everything.”

Maomao was working on the physicians’ surgical garments. They might have belonged to her superiors, but that didn’t mean she could be dainty with them. If they didn’t get the bloodstains out now, it would only get harder with time.

“Maomao, please don’t splash my mistress with filthy water,” said En’en, herself irately scrubbing at the blood. They each had a job: Maomao was working on the surgical outfits, Yao on the bandages, while En’en dealt with any particularly stubborn stains.

“Yes, ma’am.” Maomao moved her bucket farther away from Yao and resumed stomping.

“It would be perfect if we had some daikon radishes to help get the bloodstains out. Didn’t we do that before?” Maomao asked. Grated daikon was a good way to get blood out of cloth.

“Yes, well... Ahem...” Yao averted her eyes.

En’en told the story for her mistress. “Last summer we were using daikon to get blood out, but there was some that just wouldn’t come out, and we used a bit too much...”

“And now they won’t let you use any at all?”

“Right.”

Daikon was really a winter vegetable. Some varieties could be cultivated in the spring or summer, but they were valuable in any case, so of course people would get angry if they overused the supply.

“Let’s just get the stains out with good old-fashioned scrubbing, then,” Maomao suggested.

“Yes, let’s,” said En’en.

“Right...” said Yao.

All three of them sighed and resumed washing.

It might have looked like the same job they had been doing forever, but there were little changes.

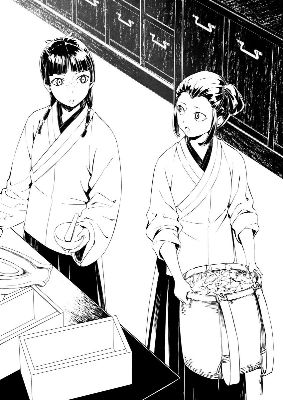

“Excuse me? We finished boiling the bandages.”

Along came two young women of perhaps fifteen or sixteen years old; they still had the glow of youthful innocence in their eyes.

The hiring of court ladies to assist in the medical office hadn’t stopped with Maomao’s year, and now here were two new recruits.

What were their names again?

Unfortunately, remembering other people’s names and faces was not a Maomao specialty. She mostly just played along with whatever conversation was happening while keeping in mind that the two of them were junior to her.

“All right, boil these too, then, please,” Yao said, handing the girls the laundered bandages. She took a somehow older-sisterly tone with them—since they were both younger than her and below her in rank.

“Yes, ma’am.”

Without another word, the two juniors took the basket and walked away.

“Huh!” said Maomao.

“What is it?” En’en asked, looking at her.

“Oh, nothing. I was just thinking we have a couple of very obedient young charges.”

Many of the young ladies at the palace were there either to gussy up their resumes for marriage, or specifically in hopes of meeting a nice man to settle down with. Many of them also came from families with plump purses—not the kinds of ladies who were accustomed to doing odd jobs and menial labor.

“There were a few others who came in with them. I chased them out on day one, though.” Yao gave a snort.

“Chased them out?”

That had happened once before, Maomao remembered.

“I don’t mean I made them quit. I just pushed them into other departments.”

“And only those two were left?” Maomao gave a knowing nod. They seemed like rough-hewn young ladies—it wasn’t that they were plain looking, but they were still unpolished. “I get the sense that they come from the countryside.”

One of them was short and had her sleeves rolled up; the other one was tall, and her work uniform was impeccable.

“You’re right. But one of them used to serve in the rear palace,” Yao said.

“The rear palace? Really?”

“Uh-huh. The tall one is named Yo. The little one is Changsha. I know you, Maomao—you probably don’t remember those names yet, do you?”

“Ha ha ha,” laughed Maomao, but Yao knew her all too well.

The big one has a short name, and the small one has a long name.

“They teach the palace women academic subjects, right? Yo proved to be an excellent student, so they asked her if she wanted to be a court lady.”

“Huh. I always assumed they tried their best to keep people like that in the rear palace.”

The term of service in the rear palace was two years, and a girl from a poor family would be turned right back out when her time was up. It seemed Jinshi’s efforts to raise the literacy rates in the rear palace in hopes of giving such women some kind of shot at finding work were bearing fruit.

“Apparently Yo declined to stay in the rear palace. She moved to the capital in the first place in hopes of being able to save up money to send to her family. She took the court ladies’ service examination in hopes that she would be able to be with them more often.”

“How very filial.” Maomao said earnestly. There was, however, something that nagged at her when she looked at Yo. “Isn’t it hard to do the wash like that?”

The girl with the short name had her sleeves pulled down all the way to her wrists, which had to make for very hot work laboring over a pot of boiling water at this time of year.

“I asked her the same thing, but all she would tell me was that she wasn’t allowed to show too much skin or something.”

“I see.”

Li was a big place. People from all over the country gathered in the capital, each with their own customs. Some people thought small feet were beautiful, for example—or that it was unseemly to show too much skin. The old saying held that when you went somewhere new, you should do as they did, but no one could force you.

I guess as long as she does her work, it’s no problem.

Maomao, unperturbed, went back to doing the washing.

Ever since her return to the central region from the western capital, Maomao had been entrusted more and more frequently with the management of the medicine cabinet. That job made her very happy, but the number and variety of medicines had increased considerably, so it also kept her very busy.

She had to take inventory and check which medicines had expired, dispose of anything that was too old, and order anything they needed more of. They also always needed to stock common household medicines; if they were running low on anything, Maomao had to make it herself.

The room that housed the medicine cabinet had an excellent breeze and was nice and cool; the room for compounding medicines, which was adjacent to it, had a well nearby and a stove, so once in a while some physician who also happened to be a skilled cook would make their lunch in there.

Maybe I can have En’en make me something one day.

Maomao wasn’t the only person who looked after the medicine cabinet; some of the physicians did as well—but if she let them handle everything, she risked being taken back off of this job she’d finally been given, and she didn’t want that, so she made sure to do very attentive work.

The laundry had taken up a lot of her time, so now she really had to get moving.

We don’t have enough pills. Better make more.

Maomao arranged the necessary items on the table. She was just trying to reach the mortar on top of the medicine cabinet when a figure appeared outside the room.

“E-Excuse me, what should I do with this?” It was Maomao’s junior, the one with the short stature and long name. She was holding a basket stuffed with dry grass.

“Give it here,” Maomao said and took the basket. A refreshing scent tickled her nostrils.

It was all well and good that the young lady had gone and gotten the requested herbs, but she evidently didn’t know what to do with them. This was the problem with physicians who just told their rookies to watch and learn.

“I assume you were told to preserve them,” Maomao said. “You can see how unwieldy they are to handle in this form, and besides, they’ll rot if we leave them this way, so we convert them into a form that’s easier to store. Watch me, observe what I do, and then help me. Feel free to take notes if you need to.”

Maomao took the herbs and plucked off the leaves. They were already nice and dry, so there was no need to let them dry further.

“First we separate them into the leaves and stems,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Put the leaves in here as you finish with them.” Maomao pulled out a drawer of the medicine cabinet and placed it in front of the new assistant.

The new girl didn’t say much; whether because she was diligent or because she was nervous, Maomao couldn’t tell. Maomao was perfectly happy to work in silence, but if this girl was going to be in her office, she needed to make sure she knew the job.

“You know what these leaves are?” she asked.

“Mint?” the young woman asked.

“That’s right.” Maybe the question had been too easy; the young woman had answered awfully quickly. “What does it do?”

“At home we used it to treat coughs and headaches.”

“At home?” Maomao actually stopped working and looked at the new assistant. “Did your family run an apothecary or something?” Her interest was piqued.

“We weren’t apothecaries, but my grandmother was a shaman.”

Ahh, so that’s it.

She was a little disappointed to find out they weren’t quite colleagues.

Sparsely populated villages often lacked a doctor or proper apothecary. Instead, the role would be filled by a village elder or cunning woman. Maomao didn’t believe in magic or anything of that sort. In most cases there was no evidence for it, and it was frequently used to deceive people. But she couldn’t completely dismiss the possibility. If nothing else, she could tell that this young lady’s grandmother had been one of the good shamans, on account of the girl’s knowledge. Maybe that knowledge had also helped her pass the written examination, which tested an applicant’s understanding of herbs and medicine.

I think there may be some talent to work with here.

She’d had to practically beat the knowledge into Sazen when she’d wanted him to take over the apothecary in the pleasure district for her; this girl seemed likely to be more self-motivated in her studies.

“While we’re at it, I want to make up some common medicines. Help me with that.”

“All right.”

Maomao’s junior watched closely and imitated her. Maomao took some of the herbs that had been sitting on the table.

At that point, a blobby creature, rather like a jellyfish, approached them.

“Hey, there! Whatcha doin’?” It was, needless to say, Tianyu. “Are you teaching the new girl, Niangniang? She’s the short one, so this must be...Changsha, right?”

He doesn’t even remember my name, but he remembers hers?

Regardless, he was correct. Right, her name was Changsha.

Maomao knew that if she showed any annoyance, Tianyu would only find it funny and needle her some more, so she ignored him.

“Y-Yes,” Changsha said. “I’m receiving some instruction from my esteemed senior, Maomao.”

“Ha ha ha ha! Listen, Niangniang has a tendency to break into a dance when she sees a strange new medicine, so watch out!”

Two could play at that game.

“Ha ha ha ha! Listen, Tianyu has a tendency to do the same thing when he sees a dead body, so watch out!”

“Uh... Strange new medicine? Dead bodies?” Changsha looked from Maomao to Tianyu and back.

“You’re going to confuse the new girl, so if you would kindly butt out? Maybe find yourself some real work to do?”

Maomao put the dried leaves in the mortar and began crushing them. “You don’t want to try to mix everything together at once,” she advised Changsha. “Make sure they’re good and crushed, then mix them. You want the powder to be as fine as possible.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Hey, hey!” Tianyu was proving very persistent.

You know, that reminds me...

Back in the western capital, she’d heard a story that he was a descendant of Kada. She didn’t know just how true it was, but since Joka’s story had been something more than fiction, maybe there was something to it.

I wonder if Tianyu knew Wang Fang.

When they’d handled Wang Fang’s body in the freak strategist’s office, Tianyu had acted like it was just another corpse. Maomao would have expected some sort of reaction if Wang Fang had been someone he knew.

Maomao didn’t stop working, even as she pondered. “Once the leaves are powdered, mix them up according to the prescribed proportions. We used refined honey as a binder.” She showed Changsha a viscous substance in a pot.

“What kind of honey is that? Is it like ordinary bee honey?”

“It’s what you get when you heat bees’ honey. Untreated honey has a lot of water in it, so we want to get some of that out.”

“Ah, that makes sense.”

“Hey, you two!” said Tianyu, still not getting up.

Maomao mixed the refined honey into a concoction of several kinds of powdered herbs. It was like making noodles: It was amorphous at first, then gradually began to take on form. She was left with a sphere of claylike material with a distinctive aroma.

“You want it to be about as soft as an earlobe,” she said. “There’s a wooden mold on top of the cabinet, so—Ah, you there, the physician! Could you get the mold for us?” she asked, finally speaking to Tianyu.

“You only want me around to do chores for you,” he grumbled, but he seemed pleased that she was finally engaging with him; he got the mold as requested.

“Thank you very much. You may go. Anywhere else.”

“You’re not very nice to me, you know.”

It was just the way Maomao always treated Tianyu, but Changsha evidently couldn’t stand to watch, because she said, “D-Doctor Tianyu, thank you very much. You really were a big help.”

“Hee hee hee! Don’t mention it!”

“You’re still so young, but they say you already do the same work as a middle physician. And I hear you’re an especially talented surgeon,” she went on.

“Heh heh! I mean, I guess.” Tianyu, perhaps unused to receiving praise, gave a somewhat creepy grin.

“How did you learn to administer such precise treatment?”

“Oh, I cut up a lot of dead—”

Maomao kicked him in the shin.

“Yowch!” Tianyu hopped on one leg. “Niangniang, what do you think you’re doing?!”

She gave him a toothy scowl.

What does he think he’s doing, blabbing about the dissections like that!

That the doctors did such things was supposed to be a secret—not something Tianyu should be chattering about to a newcomer like Changsha.

“Huh? O—Oh,” Tianyu said as his mistake finally dawned on him. He blinked, but only with one eye. It was as irritating with him as it was with Chue, albeit for different reasons.

“My dad was a hunter, you see. So I’m used to butchering wild animals.”

“Butchering wild animals makes you good at surgery?” Changsha asked.

“Well, there’s a big difference between people who have seen blood before and people who haven’t.”

The story matched up with the one Maomao had heard from Dr. You in the western capital.

“So your father was a hunter?” Maomao asked, pretending it was the first time she’d heard about it.

“Uh-huh.”

“Maybe I could visit your house sometime, then?”

“What? You wanna meet my dad?” Tianyu looked at her, allowing his eyes to shine theatrically.

“No. No. I’d just like some nice, fresh meat. It’s hard to get in the capital, right?”

“Oh.” Tianyu took Maomao’s meaning: She wanted livestock that she could dissect. To the listening Changsha, though, it would sound like they were just talking about getting some food.

Maomao’s real intention, however, was to see exactly what kind of place Tianyu came from.

“I’d love to share with you, really, but I can’t. Dad disowned me.”

“Gee, that’s too bad.” Still Maomao didn’t stop working. She packed the claylike lump of herbs into the mold, then pushed it together to produce nice, round balls of medicine. “All right. If you would kindly get out of here eventually? Surely a busy physician like yourself has other work to attend to.”

“Aww, but I can help!”

“Thank you, but we don’t need any help. Get going, or I’ll tell Dr. Li—you know how much muscle he’s put on. In fact, he’s kept it on even after we got back to the capital. Did you know he hung a sandbag from a tree in his garden and spends all his time punching and kicking it? And that on his breaks he sometimes goes down to train with the soldiers? Do you want to be a sandbag?”

“Yikes! Scary!”

Maomao wasn’t sure where Dr. Li’s routine was going to lead him, but he seemed to be living his best life. Tianyu, thoroughly intimidated by the prospect of the bulky doctor, slunk away.

“Dr. Tianyu is a very unusual man, isn’t he?” Changsha said.

“Yes. You’d be best off steering clear of him,” Maomao replied, as she pressed out more medicine balls.

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login