CHAPTER FIVE

There was a sweetish charred scent.

Perhaps honey bread was burning.

If so, the baker responsible was making a fool of himself.

But Lawrence soon realized the smell wasn’t food being overcooked.

He remembered the smell, along with the fire.

It was the scent of an animal.

“…Mmph.”

When he opened his eyes, he saw the starry night sky above him.

A beautiful gibbous moon hung in the sky, and Lawrence felt as if he were lying underwater.

It seemed that some kind soul had put a blanket over him, and although he was fortunately not shivering from cold, his body was strangely heavy.

Wondering if it was the residual effects of the liquor, he tried to sit up—which was when he noticed.

He raised his head and peeled back the blanket.

There was Holo, sleeping comfortably, soot smudged on her forehead and cheek.

“Ah, so it was this…”

She seemed to have had quite a good time.

Her beautiful bangs had been slightly singed, and as she breathed, her breath carried the burnt smell to Lawrence’s nose. Added to that was Holo’s own sweet scent along with the scent of her tail, and Lawrence realized that was what he had smelled in his dream.

The sleeping Holo did not have her robe on, and her ears were exposed.

The squirrel fur had indeed fallen right next to her head, so Lawrence could see that Holo had made a vague attempt to hide her ears.

Since they weren’t surrounded by adherents of the Church pointing spears at them, it seemed unlikely that Holo’s secret had been discovered; Lawrence let his head fall back as he sighed.

He then took his hand off the blanket and rested it on her head.

Her ears twitched, and her even breathing stopped.

She then shivered as though sneezing and curled up more tightly.

Her arms and legs fidgeted around, and finally her face moved as she rested her chin on Lawrence’s chest, then sat up.

The eyes that stared at him from under the blanket were still glazed, as though half-asleep.

“You’re heavy,” said Lawrence, at which Holo covered her face again and shivered. She seemed to be yawning, but her fingernails on Lawrence’s chest were proof enough that she was awake.

Eventually she raised her head. “What’s the matter?”

“You’re heavy.”

“Nay, my body is quite light. Something else must be weighing upon you.”

“Shall I say then that your feelings are heavy?”

“That makes it seem like I am some sort of uninvited guest.” Holo chuckled throatily, resting her cheek against Lawrence’s chest.

“Honestly…So, I assume you weren’t found out?”

“About whose bedroom I share, you mean?”

Lawrence murmured to himself that he wished she would be honest and say “bed.”

“No, I was not found out. Everyone was too roused to notice. Heh—you should have come yourself.”

“I can imagine it, more or less…but I’d rather not get burned.” Lawrence fingered Holo’s singed bangs, and Holo closed her eyes ticklishly. They would probably need to be trimmed back.

Before he could admonish her for excessive merrymaking, Holo spoke. “I heard much of the northlands from the traveling girl. Apparently they just finished working in Nyohhira. To hear her tell it, it hasn’t changed much from the old days.”

Holo opened her eyes and gazed at Lawrence’s fingers, then nuzzled his chest like an affectionate cat.

But she seemed to be doing it to scrub her face free of the emotion that threatened to show there. It was clear that she struggled to restrain the emotions that welled up.

“Always so stubborn,” said Lawrence, and Holo curled up.

Just like a stubborn child.

“We have time to decide what to do, though. We’re chasing Eve first, after all.”

Holo’s pointed ears were against Lawrence’s chest, so she surely noticed his chuckle.

Digging into his chest with her fingernails, Holo sniffed her objection.

“Would you get off me? I’m thirsty.” Lawrence had drunk a lot.

And he didn’t know whether it was the middle of the night or just a few minutes until dawn.

Holo didn’t move for a moment, and Lawrence wondered if she was being malicious, but at length, she shifted and moved.

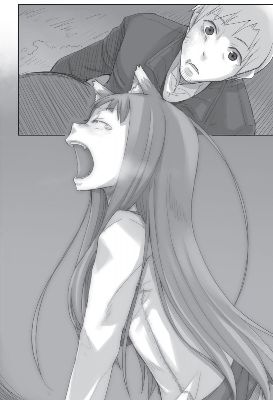

Then, straddling him like she would a horse, she tilted her head back as though she was about to howl and yawned a great yawn.

It was a strangely captivating, untouchably divine sight, and Lawrence found himself fascinated by it.

Having satisfied her desire to bare her teeth at the moon, Holo sleepily smacked her lips a few times, then closed her mouth as she wiped the sleep from the corners of her eyes. She then smiled faintly as she looked down at Lawrence.

“Being on top does suit me, I must say.”

“And I’m under you—literally, this time.”

The fringes of Holo’s ears were lit by the moonlight.

With their every movement, the moonbeams seemed to dance.

“I daresay, I’d like some water, myself…hmm? Where did my robe go?” Holo looked around, evidently not joking.

Lawrence choked back the words that came to mind—What do you think is wrapped around your waist?—and looked up at the night sky.

It was the dead of night. If this had been an abbey, the friars would have been awakening to chant the first prayers of the day.

Nonetheless, not everyone was asleep. Apart from the people curled up here and there like so many piles of cow dung, there was a circle of men sitting around the fire.

“Eyahri,” said one of the men as he noticed Holo and raised his right hand in greeting.

Holo smiled, amused, and returned the wave.

“What’s that about?” asked Lawrence.

“’Tis an old greeting. Apparently it’s still in use around the vast mountains of Roef,” Holo explained.

Since Lawrence was usually the one who was in a position to explain the world’s customs, this made him realize just how far north they had actually come.

This was really Holo’s territory now.

He remembered her profile as near the wheat fields, she had been overcome by the memories of the north to which she thought she would never return.

He wanted to put into words, to say it—You want to stop heading for Kerube, don’t you?

But if he did, she would certainly turn angry.

After all, he didn’t want her to speak those words, either.

“Ah, the boy’s awake,” declared Holo, interrupting Lawrence’s uncharitable thoughts.

While everybody had more or less lay down and gone to sleep wherever they pleased, people seemed to be collected in a certain area—but off in one corner was a small form that seemed to be doing something.

To Lawrence’s still liquor-blurred eyes, it looked like it might have been Holo.

Which meant it was Col.

“What’s he doing?”

“Hmph. Looks to be writing something,” said Holo.

Though he could make out the boy’s outline in the moonlight, Lawrence couldn’t see what Col’s hands were doing—he could only see that he was looking down and doing something with what looked like a stick or branch.

Col might well have been studying with his free time.

“Anyway, water. My throat is burning.”

“Mm.”

Taking the water skin that Holo seemed to have gotten from somebody, Lawrence stood at the riverbank and untied its string.

It was empty, of course, and the drinking spout seemed to have been rather chewed up.

Lawrence looked at Holo, who avoided his gaze. Perhaps she liked to chew on things and had simply hid it from him thus far.

Perhaps she was worried about seeming animalistic.

No—more likely it was that such a childish habit was not something a proper wisewolf would indulge in.

Lawrence’s smile was so faint that in the moonlight it was imperceptible, and he filled the water skin. The river water on this winter’s night felt like just-melted ice.

“Guh…” He filled his mouth with the painfully cold water.

Lawrence could drink any amount of water after drinking so much wine.

“Come, give it here,” said Holo, snatching the water skin away and drinking from it—then coughing, which was only as much as she deserved.

“So, did you hear any interesting talk?” asked Lawrence, patting Holo’s back as she coughed and realizing that her movements were a bit exaggerated. If you want me to pay attention to you, just ask, he thought—but did not point out her lie.

“Kuh…whew…Interesting talk, you say?”

“You said you heard about Nyohhira, didn’t you?”

“Mm. Nobody knew the name of Yoitsu, but many had heard of the Moon-Hunting Bear.”

Since even Lawrence had heard stories of the great bear spirit, it would be stranger if people in this region did not know the tales.

It was a bear spirit whose tales had been passed down over the centuries—perhaps even the millennia.

Lawrence hesitated momentarily but eventually spoke his mind.

If Holo became angry, he would blame it on the wine.

“Does that make you jealous, I suppose?” When it came to the question of whose name had been remembered, Holo was no match for the Moon-Hunting Bear.

Of course, back in the village of Pasloe, every child knew her name, but that was on a completely different scale than the Moon-Hunting Bear.

She might feel a certain amount of competition, having come from the same era.

Just as Lawrence was thinking that no, Holo would be above such pointlessness, she replied.

“Just who do you think I am?”

Her right hand held the water skin, and her left was on her hip, her chest thrust out.

She was Holo the Wisewolf.

Lawrence cursed himself for asking a stupid question, but just as he was about to say, “Ah, you’re right,” Holo slipped in another statement, cutting him off.

“I’m a late bloomer, after all. I’m only just getting started.” She bared her fangs and smiled. She was shameless, indeed, to have lived so many centuries and yet claiming to be only getting started.

Before she was a wisewolf, Holo was Holo.

“I may have retreated from being worshipped, but ’twould be lovely indeed to have a thick book of tales recorded about me, of course.”

“Ha-ha. Shall I write it, then?”

Many merchants took up the pen.

Not having learned the finer points of composition, their writing was not beautiful, but if someone on the verge of death had a fortune, they might well have a comrade take dictation for them.

“Hmph. Though if you were to do it, the travels with you would be the larger part.”

“Well, yes.”

“I can’t have that now, can I?”

“Why not?” asked Lawrence, and Holo coughed.

“It might well end up being less of a book and more a litany of humiliations.” Holo chuckled through her nose. “You’re perfectly happy to lie—you’d embellish things that did and didn’t happen, no doubt. What sort of book would you create?” Holo looked up.

It was clear from her face that she had gone beyond smiling and was now playing a foolish game.

Lawrence was a merchant.

Carefully estimating her thoughts, he spoke. “Are you trying to say I’d be as thick as the book I’d write?”

Holo laughed voicelessly, her shoulders shaking, and she smacked Lawrence’s arm.

It was a foolish conversation.

“Anyway, all I heard tell of was Nyohhira. They don’t often go into the mountains of Roef, they said. Apparently ’tis not so nice a place.”

“Huh?” Lawrence asked.

Holo was still smiling, but there was a gaping hole behind that smile.

She was stubborn.

Whenever she seemed strangely cheerful, there was always something behind it.

But she continued speaking, as though she hadn’t heard Lawrence’s inquiry at all.

“There are more than twenty hot springs. The earth has cracks that vent steam, and it seems like the end of the world—just like it did in my time. The one annoying bit was that the spot that I’d found and only I knew about seems to have been discovered—even though it was a hot spring hidden in a canyon so narrow I had to take this form just to fit.”

It was said that the spirits of the hot springs watched those who visited, and the more effort one put forth to soak in the waters, the more effective the water’s healing powers would be.

So when it came to why the people of Nyohhira would go to such lengths, it was because finding such a hot spring was part of what they lived for.

In such circumstances, it would have been discovered sooner or later.

Holo seemed exceedingly frustrated, but Lawrence could tell it was an act.

She had let something important slip.

The mountains of Roef were not a good place.

It had been carelessness.

That much was obvious.

Had the boatmen mentioned what awaited those who headed up the Roef River?

One had said that there was a mine that produced copper-like water from a spring and that there was a town with copper plentiful enough to build copper-plated stills.

And Ragusa was carrying large amounts of copper coin down the Roam River.

What was needed to make those coins?

Copper obviously—and large amounts of fuel wood or the black stone known as coal.

Holo had been talking to the troupe of performers, so if they were speaking ill of an energetic mining town, it wasn’t because the town was in decline.

It might mean that the place was unfit for human habitation.

Clear-cut forests, poisoned rivers.

Floods and landslides were common, and it would attract men trying to get rich quickly.

The performer girl may have meant that the quality of the patrons was poor, but the quality of a town’s population was determined by its environment.

It was even written in scripture that a bad tree would produce only bad fruit but that a good tree could produce only fine fruit.

“Heh. This won’t do. At this rate, I won’t be able to hide anything from you,” said Holo suddenly, just as Lawrence was wondering what he should say.

“There have always been fools who dig into the mountains. Time passes and men grow more numerous. I was prepared for that much.”

Lawrence very much doubted these were her true feelings.

After so many centuries in Pasloe, Holo had to know—she had to know that the wisdom of humanity had progressed to where some now conceitedly thought they had no need for gods.

“Still, know this—,” Holo said, taking careful step-hops as though crossing a creek via stepping-stones. She took one step, then another, and on the third step, she looked back at Lawrence. “This is my problem to worry over. When I see you make that face, I can’t worry about it properly.”

It would have been easy to simply tell her, “Why, the nerve!”

But Lawrence could hardly do so.

Holo couldn’t very well help but worry, and if they found Yoitsu in ruins, she might come apart entirely.

And yet she herself understood that her concern was nothing to be ashamed about—that it was entirely natural.

Lawrence reevaluated his thoughts.

Holo was not the girl she appeared to be.

“When the time comes, I may need to borrow your chest to cry upon. That’s one promise I’ll need from you.”

When he heard such words from a girl like Holo, Lawrence had no choice but to tell her she could rely on him.

Holo chuckled. “But then what of you? Did you hear any interesting talk?”

Led on by Holo, Lawrence started to walk, looking over at the circle of men as something in their conversation caused a stir.

“…Let’s see. I seem to remember Ragusa saying something…”

Perhaps because of the state of his liquor-muddled mind when he’d talked to Ragusa, the memory did not come instantly. He tapped his head several times, annoyed at the failure of his ledger-like memory for recalling the things he’d seen and heard.

“I believe…it was something funny…but not really funny…Something like that.”

“About the boy?” Holo suggested. Col was still off staring at the ground there in the moonlight.

The memory came drifting back to Lawrence.

“Oh yes! Or…was it?”

“Well, that’s all you and that boatman would have to talk about, is it not? And you’re competing over him, too.”

“I’m not competing over anything. But Ragusa really seems to want the boy.”

Lawrence had a vision of the fierce attack that would happen when they got to Kerube.

It was by no means guaranteed that the boy would safely become a high-ranking priest and that was only if he managed to finish his studies. When Lawrence thought about it that way, he felt like it might be good for Col to become Ragusa’s apprentice—but that was just his own personal judgment.

Holo looked up at him as he mused.

“And what of you?”

“Me? Well, I…” Lawrence prevaricated, sidestepping Holo’s sharp eyes.

He wouldn’t mind taking an apprentice if it was Col.

But it felt premature, and there was another reason he was being evasive.

“Back in Pasloe, I waited a long time for a suitable-looking traveler to come, but that good meeting did not come for some time. When it comes to people, well, you should trust my eye.”

Lawrence noticed that somewhere along the line, Holo had taken his hand.

“And he’s gotten attached to me, but worry not. He’s not likely to become your enemy.”

Lawrence turned definitively away and exhaled a long, deep, white breath.

Holo snickered.

Lawrence faced ahead, exasperated, but he wasn’t sure if Holo realized…

Did she realize that Lawrence was suspicious of her motivations for supporting Col?

“Well, everything seems to be in order now. When I heard that ships were piling up, I expected more of a scene.”

“…You were excited, then?” asked Lawrence, and Holo looked up with a complicated expression.

She neither shook her head nor nodded.

Instead, she spoke meditatively, looking off into the distance. “I did wish for a leisurely journey, but travels with you are strangely complicated—when you’ve time to think of foolish plans.”

Lawrence counted off the days left in his travels with Holo and remembered what had happened in their journeys.

It was true that given time, he did tend to think about things.

In that case, perhaps he might as well get caught up in mad thoughts, if only for the amusement of it.

But saying such things to Holo was going too far, Lawrence thought.

So he instead incited her easily roused anger. “It’s both good and bad being too clever.”

Surely Holo would say this, to which he would reply that—Lawrence constructed the exchange in his mind, but Holo said nothing at all.

When he thought it strange and looked at her, he saw her furrowed brow.

“Too clever?”

Lawrence immediately knew she was not angry.

By her expression, she simply did not understand.

Which was precisely why Lawrence could not fathom the meaning of that expression.

When he faltered and his words failed him, Holo made a small sound. “Ah—”

He felt as though that was the trigger.

Lawrence saw the source of the discrepancy.

Their gazes met.

They stopped walking simultaneously, and after a short silence, what appeared on both their faces were frowns meant to hide the awkwardness they felt.

“Don’t tell me you asked around about far-off places just because you were interested, and now you’ve gotten some strange misapprehension in your head,” said Holo.

Lawrence raised his eyebrows, at a loss for words.

Naturally, even as he hoped that his worst fears would prove baseless, he had confidence that they would be borne out.

“’Tis no wonder you made such a strange face back then. Well, you can keep your worries to yourself,” said Holo forcefully.

“I could say the same thing to you. The reason you’re trying to force Col off on me as my apprentice is exactly the same.”

This time it was Holo who drew her chin in, chastised.

It was just as he thought.

She might have saved Col out of kindness, but her strange fawning over him and her insistence that Lawrence take him on as an apprentice was for another reason entirely.

So what happened if he applied his new knowledge that when Holo did something, it was for his own sake?

Before long, he saw that his worries about Holo were the same as hers.

They glared at each other, both trying to look firm.

“You’re the weak one, and I’ve got to protect you,” they each insisted.

It was a foolish conversation—they were both thinking the same thing.

“Honestly…so what was it you wanted to say?” said Lawrence with a little sigh, giving up on the staring match. Holo sighed as well.

“When we’ve time to think of foolish things, it seems neither of us can think of anything good.”

“Unaware of our own faults.”

Holo smiled slightly and took Lawrence’s hand again. “One cannot help thinking such things, but it’s still quite difficult.”

“Not thinking about anything is another problem, I think…it is difficult.”

And all the more so when Lawrence realized that this was the height of that joy.

The future would be darker than this. Even if they were worried about each other, if they continued to talk of these things, no cheer would come of it.

“Come, let’s stop talking of this,” said Holo, apparently having come to the same conclusion.

Lawrence agreed.

“Well, we’ve gone to the trouble of waking up at this hour,” said Holo. “It’s cold, so let’s go talk to the lad and have some wine.”

“More drinking?” said Lawrence, flabbergasted, but Holo walked ahead of him, and her only reply was the twitching of her ears underneath her hood.

“Could these people not sleep in a more orderly fashion? They are in the way; ’tis frustrating.”

The sleeping figures were scattered here and there as though they had fallen at random out of the sky, and they made it hard to walk straight across the area.

Since it was still a wide riverbank, it was all right, but if it ever became a cheap lodging house, this would surely be one of the complaints.

If they had lined up nicely, they could have stretched out their legs and there would have been room for more people to sleep, but people seemed to prefer sleeping hither and thither, their arms and legs sprawled everywhere.

It was thanks to that that Lawrence didn’t know how many times he’d had an inn right before his very eyes, but spent the night under the cold sky.

Such travel memories came to Lawrence, but something nagged at him.

He looked behind him at the sleeping forms of the merchants and boatmen. Their posture. Their direction. Their number.

Glared at by Holo, Lawrence found the nagging in his mind had vanished.

“Col, m’boy,” said Holo.

Col seemed as attached to Holo as she was to him, and she appeared to have taken a shine to the boy.

Be it “vixen” or “bird” or “old man,” Holo essentially never called people by their names.

Lawrence found himself searching his memory for any time Holo had called him by name.

It had probably happened once or twice, but when he tried to imagine the scene, it made him feel a bit embarrassed.

“Hmm?” Holo said blankly. She had called Col’s name, but the boy did not seem to have taken notice.

Lawrence and Holo looked at each other, wondering if he was asleep, then approached the crouching Col.

He didn’t seem asleep—he was wrapped in Holo’s robe and holding a thin stick in his hand and moving.

He seemed to be totally absorbed in whatever it was he was doing.

Holo was about to call his name again, but just then, he seemed to notice their footfalls and looked over his shoulder in alarm.

“—Whoops,” said Lawrence; Holo’s face was blank.

Col, for his part, seemed to have been wholly absorbed in whatever he was doing. Turning to Holo and Lawrence with a look of surprise on his face, he hastily picked something up. It made a light metallic clink, so it was presumably coin. He also tried to hide something with his feet when he stood.

Holo wasn’t the only quick-witted one.

Lawrence looked at the boy, whose feet hid what looked to be like writing on the ground.

Just as Lawrence was wondering what it was, Col quickly scuffed and erased it, then spoke.

“Wh-what is wrong?”

Going by the feel of Holo’s hand in his, Lawrence got the feeling that Holo wanted to say, “That’s my line!” He was quite sure it wasn’t just his imagination.

It was obvious Col was hiding something.

“Mm. We woke up at this strange hour and thought you might drink with us.”

The unpleasant face Col made was certainly not a joke.

Not long ago, Ragusa had forced the boy to drink, and Col had passed out.

Holo chuckled. “’Tis a jest. Are you hungry?”

“Er…a, a little.”

Col had drawn a small circle.

It seemed he had drawn several such figures, but there was no way to know for sure.

“Mm. Come, you—,” said Holo to Lawrence. “We have plenty of provisions, do we not?”

“Hmm? Oh, well, we have some, yes.”

“But?”

Lawrence shrugged and answered, “But if we eat it, we’ll have that much less.”

Holo lightly smacked Lawrence’s shoulder. “Well, that decides it, then. Now, ’twould be nicer to be near the fire…”

Between the dancing and the drunken staggering, Holo and Lawrence had forgotten where their blanket had been laid.

They both looked at Col, prompting him to ask, “Don’t you remember?” in a slightly worn-out voice.

If Col was to indeed join Lawrence and Holo’s travels as an apprentice, this sort of exchange seemed likely to happen every day.

Holo giggled. “We were both drunk, after all. I am sorry, but could you fetch it for us?”

“Understood,” said Col and trotted off.

Lawrence and Holo watched his figure recede together, and something about the scene was far from disagreeable to him.

Part of that was of course because Holo was right next to him, but she seemed to agree and leaned lightly against him.

Lawrence knew one word to describe the scene.

But if he spoke it, he would lose.

“You—,” Holo began.

“Mm?”

Holo did not immediately continue, instead shaking her head.

“Never mind.”

“All right, then.”

Lawrence, of course, knew what Holo was trying to say.

And yet he got the feeling he shouldn’t be thinking about it.

“By the way—,” said Lawrence.

“Mm?”

“Col’s hometown, apparently it’s called Pinu. Have you heard of it?”

Col seemed to have accidentally stepped on one of the sleeping figures in his haste.

Lawrence smiled as he watched the boy apologize and squeezed Holo’s hand a bit.

“What did you just say?” Holo’s voice was not her ordinary one.

Or so Lawrence thought, but when she turned to look at him, her eyes seemed to be smiling.

“Just kidding,” she finished.

“…Hey.”

Holo giggled. “Am I supposed to know everything now?”

She had a point, but Holo did like to pretend ignorance of important matters and treat outrageous things as if they were nothing.

If he started doubting her, there would be no end to it, but the truth was they had come far enough on this journey that making such a joke at this point was rather dubious.

Lawrence watched Holo snicker at Col’s now-careful walking, and Holo sighed, not looking in Lawrence’s direction.

“I suppose I shall be more temperate next time.”

“…I would certainly appreciate that,” said Lawrence just as Col returned.

“Did something happen?” he asked.

“Hmm? No, not especially. We were just talking about your hometown.”

“I see…” came Col’s tired reply; he was probably thinking that such a place wasn’t interesting enough to make a good conversation topic.

Most people who had even a little bit of pride in their hometown would have jumped at the chance to talk about it.

“Pinu, was it? Does your village have any legends?”

“Legends?” Col asked as he handed over their things to Holo.

“Aye. Surely you have one or two.”

“Er, well…” Perhaps he hesitated because of the suddenness of the question. Even the most meager village had many legends and superstitions.

“When you talked to me,” Lawrence said, “you said it was a problem when the Church came in, didn’t you? Which means that region, Pinu included, had other gods.”

Hearing it explained thus, Col seemed to understand.

He nodded and spoke. “Ah, yes. Pinu is the name of a great frog god. The elder claims to have seen it with his own eyes.”

“Oh ho,” said Holo, her interest piqued.

The three of them sat down, with Lawrence and Holo taking the wine and giving bread and cheese to Col.

“The place the village is in now isn’t where it used to be—that land vanished long ago in a great landslide and wound up at the bottom of a lake that was created in a flood, it’s said. Right after that landslide, the elder—who was still a child then and helping to hunt fox in the mountains—apparently saw it. The great frog was blocking the floodwaters from flowing down the valley that led directly to the village.”

Stories of gods that protected villages from great disasters existed all over.

The Church was busily trying to rewrite them all to feature its own God, but looking at Col’s shining eyes, that task seemed as though it would hardly go well.

Stories of gods and spirits were not mere fairy tales.

If the stories were even now still trusted, the Church’s efforts were pointless.

“So Lord Pinu blocked the floodwaters, and as he held them back, the elders came down the mountain and ran to the village to warn everyone, who barely escaped with their lives.”

Once Col had finished the telling, he seemed to realize he had gotten a bit excited.

He looked around, wondering if his voice had been too loud.

“Hmm. So your god was a mere frog, then. What of, say, wolves?” Holo couldn’t help herself apparently.

Thus asked, Col’s answer was quick. “Oh yes, there are many.”

Holo nearly dropped the jerky she had taken out of the sack, but she managed to feign composure as she put it in her mouth.

Lawrence pretended not to notice her trembling hand.

“But there are more of those in Rupi. I told Master Lawrence of that place—it’s where the skilled fox and owl hunters are.”

“Ah, the village that the Church marched into, yes?”

Col nodded with a rueful grin, because it was that event that had been the cause of Col’s journey in the first place.

“There is a legend that says that the ancestor of Rupi’s people was a wolf.”

The part of the jerky that stuck out of Holo’s mouth twitched impressively.

Lawrence was impressed she hadn’t dropped it.

But then he thought back to the pagan town of Kumersun, where he’d talked to Diana the chronicler woman.

She had spoken of a human and a god becoming mates.

He had asked for Holo, who was terrified of loneliness, but now this all took on a slightly different meaning.

As Lawrence hoped he wouldn’t be teased too much by Holo for this, Col continued. “This is just talk I heard later, but apparently the Church men who came to Rupi originally had that wolf-god as their goal.”

“The…god?”

“Yes. But there are no gods in Rupi. According to the stories, they died.”

Lawrence didn’t understand.

If the legend held that the gods were dead, it was strange that the Church would come looking for them. It would have made more sense for the Church to have come because the gods were dead, as that would make the propagation of its teachings easier.

And the high priest that also served as the Church troop’s commander had pulled out of the area when his health failed.

It was a strangely halfhearted engagement.

It almost sounded like the Church had only come in search of something.

That was when Lawrence realized.

The men of the Church had come looking for something—they had, all the way out to a remote village, whose god had already died.

“Long ago, the story has it that the god of Rupi returned to the village after being terribly injured, then died there. As thanks, it left its right foreleg and its offspring there. Its offspring were accepted into the village, and it’s said that the right foreleg protected the whole area from plagues and disasters. And the Church men were looking for that foreleg or some such.”

Col’s relating of the story made it sound like a fairy tale; he did not seem to really believe it himself.

It was not uncommon for people to consider their home village’s legends rather banal after having traveled and seen some of the breadth of the world, even if they’d never doubted those stories before.

“That is what they say, but our village fell into a lake after a landslide, so it’s a bit doubtful whether the god of Pinu really left its leg there,” Col said with a smile.

Having been outside and gained some wisdom, it was natural that he would see the discrepancy between legends and what happened in reality.

Such experiences would serve only to shake his faith, the stories passed down in his village.

But Lawrence was the opposite.

Thanks to Holo, he now knew that such stories were no mere fairy tales.

And it was his nature as a merchant to try to incorporate this information with what he already knew.

It was enough to call up a vague and fuzzy memory.

Something he had heard from Ragusa, just before passing out drunk.

He knew full well that it was an arbitrary conclusion.

And yet, it fit perfectly.

“So, do you doubt the legends?”

Holo immediately sensed the strange atmosphere and looked dubiously out from beneath her hood.

The boy smiled slightly. “…If you mean do I not fully believe, then yes, I doubt them. But in school, I learned a lot about reconciling the existence of gods. So it’s simple. The foreleg of Rupi’s god would decades ago have been…”

Col had had many experiences in his school in the south, then thinking of returning home, had found himself in this area.

Without question, it would be normal to collect stories about one’s home.

Which meant that it would not be strange if Col had collected the same information as Lawrence.

The big difference between Col and Lawrence was whether or not they believed in the preposterous tales.

Lawrence did not venture to look at Holo, only taking her hand. “Treasure maps appear only once the treasure has already been stolen.”

Col’s eyes widened.

Then they narrowed as he smiled with faint embarrassment.

“I won’t be fooled again,” his face said. “Still, that can’t be, can it? Buying and selling the foreleg of a god, I mean.”

“—”

The sound of Holo breathing in.

It seemed Col did indeed have the same information as Lawrence.

Holo’s hand gripped his very tightly.

In place of speech, Holo gave him a look, but Lawrence did not return it.

“Yes. The world is full of frauds and fakes.”

Lesko, the town at the headwaters of the Roef River. The trading firm there had been looking for the fossilized foreleg of a wolf-god.

Based on the information Lawrence had gotten from Ragusa over drinks, it was certainly a rumor that was circulating among the boatmen.

And if Col, who’d been living on the road, had heard it, it was likely a topic of discussion at inns and taverns that attracted travelers.

The saying was “where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” but it made more sense to ascribe the rumor to the pagan culture that suffused the northlands.

In his seven years as a traveling merchant, Lawrence had heard such tales more than a few times.

The remains of saints, the wings of angels, miraculous chalices, even the robes of God.

And they were all laughably absurd fakes.

“Um, I really don’t believe any of this, you know.” Col seemed to think that Lawrence’s and especially Holo’s silence was due to their being shocked at his naiveté. “I mean, of course I think I’d like to know for sure if it is true, but…”

His lonely smile as he said this was like that of a child who has realized the trick behind a sleight of hand.

How would he react if he knew that before his very eyes was a living relative of that same god?

Lawrence couldn’t help but wonder.

But when he considered whether Holo would want to show Col her true form, he couldn’t imagine it was so.

She instead looked at Col with terribly calm eyes.

“Still, if the Church really is chasing after that bone, what could they be thinking, I wonder?” said Lawrence to Holo, bringing her into the conversation.

He had noticed Holo’s state, but given the topic, she must have some thoughts on the matter, he reasoned.

“What are they…thinking?”

“Right. I mean, if they’re trying to find that bone because it’s genuine, that would confirm the existence of the pagan gods. Surely they won’t do that.”

“That’s true…,” murmured Col, his face blank. “Now that you mention it, that is strange.”

If it was real, the bone was surely from a wolf like Holo, so its size would be far from ordinary.

Lawrence’s memory was a bit hazy, but he seemed to remember Ragusa saying something about a hellhound.

When they found the bone, perhaps they would simply call it something like that and make a religious proclamation of it.

If it had been a martyred saint, Lawrence could think of any number of ways to use them.

Just as Lawrence was thinking it over, Col raised his voice uncertainly.

“Ah, er, maybe—”

Lawrence looked at the boy; perhaps he had hit upon something. But just then, the circle of men around the fire cried out in laughter; evidently something had been funny.

And the next moment—

Krakk—there was the sound of something breaking.

For a second, he suspected Holo and her ill temper.

When he cast his gaze at her, Holo was a bit surprised but met his eyes and seemed to have understood Lawrence’s immediate reaction.

She smacked his shoulder.

“Wh-what was that…?” Col murmured, terrified despite having only just declared his skepticism over the existence of gods.

Perhaps the conversation had gotten to him.

Religious faith is not so easily lost—Holo seemed pleased to see this and looked about to laugh.

There was no sound for a moment after that, and the men around the fire, having all got to their feet, began to sit back down, and a few of them looked at Lawrence and the rest and shrugged.

What had it been? Everyone wondered the same thing. And then—

Again—krak, kreak—the breaking sounds continued, now noticeably louder, as though something was splintering.

The river.

Just when the thought hit Lawrence, there came the sound of creaking lumber and then a great and audible splash.

Col got to his feet.

Lawrence was on one knee as he looked at the river.

“The boats!” cried the men who’d been drinking around the fire.

His gaze soon slipped to the river’s surface.

What he saw was the gallant form of a large ship as there in the moonlight it seemed to be making its departure.

“Ahoy! Somebody—!”

The men who had been drinking around the fire all shot to their feet, but not a one of them took action.

Perhaps they were all merchants and travelers. Lawrence also stood, and Col started to run, but after taking three or four steps, he realized he didn’t know what action he would actually take and stopped short.

It was clear that the boat was about to float down the river, and it was equally clear that it had to be stopped.

But Lawrence didn’t know how.

Just then, a voice called out.

“Protect the ship!”

At the sound of that voice, the boatmen who had been sleeping scattered about like so much cow dung now jumped to their feet.

All of them ran for the river, as though having dealt with this sort of thing more than a few times.

Despite having been drunk not long ago, most of the boatmen’s strides were steady and confident.

The first among them to reach the boats moored at the river’s edge were Ragusa and another man.

They strode directly into the water, raising a splash, pushing against the hull with ox-like strength.

Ragusa boarded first, followed by the other man.

Shortly behind them, the rest took the next best course of action, jumping into the river with a moment’s hesitation and swimming toward the anchored boats.

The big ship was slowly but surely being pushed over the other, sunken vessel and would soon be swept downstream.

The sunken hulk, after so many attempts by Lawrence and the rest to haul it ashore, must have grown fragile and given way.

And now it was being crushed under the other ship’s weight.

If the ship was swept away, it would almost certainly run aground at the next meander or sandbar.

And there would be other vessels anchored farther downstream, as well.

If a smaller boat happened to be struck, even a child could tell you what would happen.

But the reason the boatmen plunged into the crisis like well-trained knights seemed less for fear of the actual consequences and more to simply protect their good names as boatmen. If they let the same ship run aground twice, it would destroy their reputations.

Col took another two or three steps, perhaps drawn forth by Ragusa’s bravery.

Lawrence gulped as he watched the developing situation.

After all, the ship was one that required four or five rowers. He didn’t think it would be easily stopped.

But unlike the rest of the onlookers, Lawrence was not simply staring at the sight.

Next to him was Holo, who murmured, “Do you really not understand?”

“Huh?”

For a moment, he thought she was talking about the ship, but then he realized that wasn’t it—she was referring to the reason the Church was searching for those bones.

“Do you understand?” he asked back.

A cry went out.

When he looked, he saw that Ragusa had with admirable skill managed to get his boat alongside the runaway ship, and the other boatman had jumped aboard the larger vessel and taken up its pole.

But it did not seem like it would stop. In the moonlight, that pole seemed impossibly thin and fragile.

He thought he could hear Ragusa’s nervously clicking tongue.

“I do understand, in fact,” replied Holo. “Just as you live by traveling and selling, I lived on the people’s faith.” Her sharp words were the proof of her displeasure.

Lawrence didn’t know why she was angry.

But he knew that her anger had something to do with the Church.

“The reason I so hated being called a god was the way people kept me at a distance, gazing on me from afar. They feared, respected, and were grateful for my slightest move. I was treated with constant and terrible caution. So if you consider the opposite of that…”

“No!” someone called out.

Ragusa’s boat had circled ahead of the ship. If the boatmen tried to encircle the ship and stop it that way, they could easily wind up sinking themselves.

There was the dull sound of hull hitting hull. All who watched the scene held their breath, fists clenched tight.

Ragusa’s boat rocked violently. Surely it would capsize at any moment. Despite the tense atmosphere on the shore, Lawrence looked back at Holo.

He understood what she was trying to say.

“Surely that bone, they won’t—”

Then came the sound of a great wave crashing.

After several moments that seemed like an eternity, the ship visibly slowed and seemed to come to a stop.

It was safe for the nonce.

The realization spread, along with a great cheer.

Aboard the ship, Ragusa raised both hands in triumph.

Yet Lawrence could take no pleasure in it.

His mouth was filled with vulgarity of the Church’s actions.

“That’s right. Suppose they find a bone they know is real, then crush it under their foot? We can’t simply devour the fools until we’re bones ourselves. We’ll have to content ourselves with being subjugated. There will be no miracles. And what will the people who see us think? They’ll think this—”

Soon the trailing boats caught up with the big ship, and several more boatmen climbed aboard and tossed ropes out.

Lawrence felt he was witnessing the indescribable solidarity of men who worked together.

He longed to be among their sudden celebration.

“—They’ll think, ‘Oh, look at this thing we so used to fear—’tis not such a great thing, after all.’”

It would be a more effective demonstration of the greatness of the Church’s god than ten thousand words of sermon.

Lawrence found himself impressed at the calculation of this—only the Church, having fought the pagans for centuries, would consider such a thing.

But that bone might well have belonged to someone Holo knew—in the worst case, even a relative.

And this was Holo, who found herself conflicted by the fur trade.

But there was a difference between trading in fur and symbolically crushing this bone.

Her eyes quivered not because she wanted to weep, but rather out of rage.

“So, what think you?” she asked.

There amid the sounds of drums and flutes, Ragusa and his comrades tied the boats together with practiced motions, setting about the task of mooring them once again.

Each man was skilled enough that no conscious thought was required and performed his task with logical ease.

The Church was just as practiced in the manipulation of faith.

They would use whatever tools they had to spread it.

“I think—I think it’s awful…,” said Lawrence

“Fool,” said Holo, stepping on his foot.

The pain he felt told him just how angry Holo was.

“I’m not asking you of the morality of this. You’re just like the Ch—”

Holo stopped herself short, but before she could apologize, Lawrence stepped on her foot, his face serious and inclined just so.

“That’s payback,” his expression said.

Holo bit her lip before continuing, partially to calm herself and partially out of frustration at her own verbal misstep. “…What I mean is, what do you think of the story that they’re after the bone? Do you think it is true?”

“Half and half.”

Holo looked at him, pained perhaps at the shortness of his answer.

She might have been regretting making him angry for no good reason.

“I mean, my immediate guess is half and half. Stories like this are common as the way Col was deceived during his studies.” Lawrence motioned with his chin at Col.

Col, along with the rest of the onlookers, was cheering Ragusa and the other boatmen.

His innocent figure looked not dissimilar to Holo’s, as he was still wearing her robe.

“Well, it’s hardly half and half, then, is it?” said Holo.

“Yes, but I know that beings like you exist. That eliminates the possibility of the most common idle gossip. So, half and half. That it’s a rumor at all is because there’s a trading firm involved. Whether it’s really in Rupi, we don’t know. That the Church came to Rupi is only true so long as Col isn’t lying.”

Ragusa and the other boatmen’s labors seemed to have concluded.

They all piled aboard Ragusa’s boat with a few energetic ones diving into the water and swimming ashore.

The remaining wood was lavishly thrown on the dwindling fire and wine toward the returned heroes.

“What say you to this—?”

“Mm?”

Holo’s hand entwined with Lawrence’s.

She seemed to think that putting on a show of teasing him was necessary when she had a favor to ask.

“Let us continue our easy travels, and when we find Yoitsu, say our good-byes. What think you?”

Lawrence had to laugh at how easily she broached the subject.

Holo dug her fingernails angrily into his hand.

This was going just a bit too far.

When she was so frank about it, he couldn’t very well accuse her of not being honest.

Lawrence took a deep breath, then exhaled. “Don’t ask me a thing like that. What did I say when I came to pick you up?”

Holo looked away and did not answer.

Unbelievably, she seemed shy.

“There is the salvation that it may all turn out to be a mere rumor. If it’s captured your interest, I don’t mind.”

“And what if there is no such salvation?” She was not called a wisewolf for nothing.

Words were her playthings.

Lawrence lightened his tone still further. “If it’s true, we won’t come away unscathed.”

“Because of my anger?”

Lawrence closed his eyes.

The moment he opened them, he saw the excited Col looking back at them. The boy seemed to notice their strangely subdued state.

He hastily looked ahead, as though having seen something he knew he shouldn’t have.

“Such items are unbelievably highly priced as a rule. The Church often brings its authority to bear in such matters, as well.”

He looked at Holo next to him.

Lawrence knew that Col was looking at them over his shoulder.

But he didn’t particularly care.

“Despite your morals, it’s a valuable item that affects the Church’s credibility. If we get involved, we won’t come away from it unhurt.”

Holo smiled, bringing her free hand up to chest level and waving.

Lawrence saw Col hastily look away.

Holo slowly lowered her hand.

“To come out and just say it, I’m going digging for bones. I won’t force you to come along.”

Now she was being unfair.

Lawrence brought his free hand up and smacked Holo’s head lightly. “Unlike you, I’d prefer our book to be a long one.”

“…In truth?”

While the idea of the journey ending by growing old and passing in his sleep had a certain appeal, there was something that was quite painful for him.

And it was all the more so when the encounters and travels had been so eventful.

Why did people gather to celebrate and dance at the end of the year or at the harvest?

Lawrence felt like he understood now.

“Stories are better when they have an ending, are they not?”

“Even if there’s danger?”

Lawrence shook his head.

He was no wild youth, after all.

“Of course, I’d prefer to avoid danger if possible.”

Holo grinned triumphantly. “I’m Holo the Wisewolf!”

It was a foolish thing, he thought.

If there really was a trading company searching for the bone and the Church was truly after it, then it was not something an individual merchant could hope to affect.

And yet, Lawrence thought.

His travels with Holo would not be some weakly strained paste that left the stomach empty and grumbling. They had to be like beef, thickly cut and smeared generously with spices.

Holo smiled softly and walked ahead.

She tapped the eavesdropping Col on his head, then walked with him toward Ragusa and the rest.

Lawrence followed slowly after them.

The moon hung there in the sky, and the pleasantly cold air stirred at the hearty laughing of the boatmen.

The turning point of their journey was a lovely night, indeed.

Lawrence took a deep breath.

Though Holo might be angry to find out, he did not much care whether the tale was true.

There was something more important than that.

“…”

For having found a reason to continue forward, he wanted to thank the moon.

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login