THE GEM OF THE SEA AND WOLF

If one were to take the form of a bird and fly over Salonia, it would look as though clusters of mushrooms were growing atop a gold-and-brown carpet. The town thrived on inland trade, and that was the sort of place it was.

It was once a vacant piece of land, used only by local farming villages for bartering produce, but that changed when a wandering priest appeared one day and built a hermitage on the spot. For the first time the area had a place of worship, so locals visited more frequently, which in turn drew the business of merchants, which then caused walls to be built, inns to open, and roads to be paved. And so, a town was born.

Salonia was known for its biannual market; the market this autumn was quite exciting, as it typically was.

Though successful at a glance, the truth was that the foundations of the market had been struggling beneath a weighty problem, a result of which caused several individuals to find themselves tossed in jail.

As the townsfolk bemoaned their concerns, a few travelers who had come to town conjured up a solution to the problem. The solution was so close to magic that it ended up recorded in the town annals.

As trouble settled on the hearts of the people of Salonia, a strange traveling couple came to town…was how that particular record began.

The husband claimed to be an ordinary retired traveling merchant, but before arriving in Salonia he had solved a mystery involving a place that was considered a cursed mountain and sold it to the Debau Company for a high price. This sharp retired merchant had erased the debts plaguing the people of the town without using a single coin.

Though possessed of an exceedingly rare sense of judgment, he always deferred to his young wife, and the people of Salonia often saw how tight a hold she had on him.

It was not long after that the townsfolk began to whisper among themselves—perhaps his mercantile prowess was owed to his wife. The rumors likely stemmed from the strangely domineering aura she possessed, despite her young looks.

The girl had flaxen hair, reddish-amber eyes, spoke like people of ages past, and was crafty yet sweet.

She was a fantastic drinker, besting every man in town who came to challenge her, so of course the former merchant in question was no match for her, either.

The pair had come to town at the beginning of autumn, and once they had made a vivid show of solving Salonia’s problem, they enjoyed their stay in town. May God watch over them…

Once she finished reading the draft of the town’s annals, Holo’s nostrils flared with pride.

Lawrence, who had sat beside her reading the same text, could not help but speak up with a strained smile.

“Why did they write more of you than me?”

“I am Holo the Wisewolf. The author knows well.”

Despite appearing to be an ordinary young woman, the truth was that Holo sported pointed wolf ears on her head and a fluffy tail growing from her backside—she was a wolf spirit, several centuries old.

She had once been regarded as a deity, and an average bathhouse owner such as Lawrence could hardly compare; her pride was only natural.

Holo had come to enjoy recording her day-to-day in a diary, but there was a considerable difference between what she wrote down herself and what others wrote.

“Can we not have a painting made of this?”

She had gotten a taste of that luxury with the mural in the port town of Atiph.

“No painting can fully convey your beauty,” Lawrence replied.

Holo was delighted at first, but she pouted at him when she realized he had tricked her.

They stared at each other in silence, but before long, both broke out into smiles.

“Why don’t we grab something to eat when we go turn this draft back in?”

“Aye, I do crave fish every once in a while.”

She had also gotten a taste for fresh fish in Atiph.

Lawrence wanted to check the weight of his purse, but he noticed how Holo was reaching for him.

He grasped her hand, and she beamed at him.

How could he resist when she smiled at him like that?

Lawrence laughed to himself—the annals were right after all. They left their room at the inn together.

As Lawrence and Holo made their way to the church to return the draft, they found a crowd of people pouring from the building; noon mass had just ended. Several merchants noted Lawrence’s presence and tipped their hats in greeting. He felt a bit embarrassed having become such a celebrity, but Holo, on the other hand, was eating it up.

It was almost as though she was saying that she was the one who had made him.

“Oh, Mister Lawrence.”

“Hello, Miss Elsa.”

When the pair stepped inside the church, they came across a priestess with her hair pulled back tightly in a bun, carrying a heavy stack of scripture.

She was an old acquaintance he had encountered not long after meeting Holo, on the road in search of Holo’s home.

Not only that, but Elsa had officiated their wedding as well; that, combined with her shrewd personality, made her the number two person who Lawrence would listen to without question—number one being Holo, of course.

“We’ve come to return the draft. It was a little embarrassing reading all of that.”

“That simply means you did a fine job. I can still scarcely believe you pulled it off.”

Lawrence had freed people from their debt without a single piece of silver changing hands. It sounded like magic when put that way, but when it came down to it, solving the underlying issue had not been all that outlandish.

Lawrence handed over the sheaf of papers, and Elsa accepted it with great care, as though there were still secrets hidden inside.

“The aftermath was the greater headache for you, wasn’t it, Miss Elsa?”

Once word spread about the way Lawrence erased debt, naturally, others began to wonder if they could do the same with their own debt. But debt was a questionable topic, and since the job entailed undoing the chain that linked everyone together, that meant the Salonia church sat at the center of it all. It was at this stage that Elsa had been called on to take charge—she was not only good with writing and numbers, but the strength of her faith was beyond doubt.

“Resolved in three days with much enthusiasm. It was not that big of a problem.”

Her clear honey-colored eyes made it obvious she was not saying that just to make him, or herself, feel better.

Lawrence bowed his head, impressed, when Elsa spoke up again.

“That reminds me,” she said. “A carriage brought in something rather interesting this morning. I was hoping to give it to the both of you.”

What she said caught the attention of Holo, who had been mid-yawn. Elsa handed them a booklet she had been carrying with her hefty scriptures.

“Selected passages from the Twilight Cardinal’s vernacular translation of the scripture. I think it has been wonderfully translated.”

There was an uncharacteristic teasing tone to the way she said Twilight Cardinal.

And the reason she had called the booklet “interesting” was not because she was a devout priestess.

The person who immediately came to mind was a young man whom Lawrence knew well: Col. The “Twilight Cardinal” was the title the world knew him by.

Elsa was one of Col’s teachers—she had instilled in him the habit of saying grace at meals when he was a child. She must have found it so strange and touching that the little boy had grown up to do such great things.

Lawrence was no less proud to see that the little boy he happened to take in on his journey had grown up to be such a renowned individual. He was even slightly jealous.

As he took the booklet, enjoying the comings and goings of all the different emotions inside him, Holo stuck her face closer to the book and gave it a sniff.

“What? ’Tis not a letter from them?”

“No. I do ask the merchants who come through to keep an eye out for their whereabouts, but…I hear all sorts of stories, about being in this town or another, or battling with corrupt clergy in another region, or—no, no, they were debating priests up on the mountain! They’ve become somewhat of a myth; everyone is making up their own stories about them. Becoming this famous has its ups and downs.”

Col had left the hot spring village of Nyohhira to pursue his dream of becoming a man of the cloth.

It did not take long for him to throw himself into an adventure that would make such waves throughout the world, and Lawrence was as concerned as ever about where the boy was and what he was doing in that moment.

“No news is good news,” Holo declared. “And to hold such a thing in our hands means he is once again holing himself up in his room, munching on onions to stave off drowsiness.”

She took the booklet, shaking it, making the pages flap.

“Can you not imagine the little fool sitting beside him, utter boredom on her face?”

When a mischievous smile crossed Holo’s face, Lawrence pursed his lips.

As she watched, Elsa commented with a smile, “Some refer to her as Saint Myuri. Constantly smiling, merciful as the sun.”

When he heard that, Lawrence was not sure if he should smile or sigh.

The biggest reason he wanted to know where they were and what they were up to was not only because Col was like a son to him, but more so that his only daughter, Myuri, had latched onto him and followed him when he departed.

Letters had occasionally trickled in after they left, but soon they arrived less and less frequently, and had now come to a complete stop. His worry that something had happened to them had only grown.

First, there was the fear that trouble had befallen them somewhere along their journey.

There was also the matter that while Col and Myuri were not related by blood, they were still ostensibly brother and sister. Lawrence often wondered if something had changed in their relationship.

“That little fool never knows when to give up.”

“I have three boys, but if you told me that one of them was going to live with his wife in a city far away, I would certainly be sad.”

“Indeed. Though one could easily visit or ask him to send all the delicious delicacies his new home has to offer.”

“That is also true.”

Views between the serious and honest Elsa and the old, crude Holo often clashed, but it was on these topics that they saw eye to eye.

“Come now, husband. Get it together. We have a job to do—namely getting ready for the festival that concludes the market.”

Holo whacked Lawrence on the back with the booklet.

“What? You just want to drink.”

“Fool. No one in this town can drink more than I can. The responsibility of choosing what drinks will be served at the festival obviously falls to me.”

Even Elsa, who would typically interject with words about moderation in times like these, refrained from saying anything; this particular instance of drinking was an actual job, after all.

“We argue every year over which granary to choose, so having Miss Holo choose for us this year should be a great help.”

“See?”

Holo lifted her chin in pride, and both Lawrence and Elsa sighed.

“This isn’t just your everyday wine. This is distilled barley liquor. Don’t drink too much.”

“You fool. When have I ever told you I have had too much to drink?”

Considering how she could proclaim such a thing loudly in a church meant that no scolding from Lawrence or Elsa would reach her ears.

“What snacks would go well with it, I wonder? Jerky, perhaps—cured with smoke strong enough to make one choke… Or honeyed candies? I find those rather irresistible.”

Lawrence could tell she was in high spirits when he saw how her tail swished beneath her clothes.

“Dear?”

“I know, I know. We’ll see you later, Miss Elsa.”

“Yes, take care.”

A somewhat exasperated, yet envious smile crossed Elsa’s face as Holo dragged Lawrence away.

Several hours later, Lawrence carried a pleasantly drunk Holo on his back as they returned to the inn.

When Salonia’s spring and autumn markets open, merchants come from all over—not just the immediate surrounding area.

The end of the autumn market was always marked with a festival that gives thanks for the harvest and prays for a good crop the following year.

When Lawrence used to travel around as a merchant, he of course attended all sorts of local festivals, but was always conflicted with himself when it came to taking advantage of the hearty festival atmosphere to sell goods at inflated prices, so he could never fully enjoy himself. In practice he kept his head down, striving to walk one step farther than his competitors, to beat them out to the next destination.

His hurried travels only slowed once he started traveling with Holo.

It was then that he started to appreciate the scenery, to truly realize how the air smelled for the first time.

The festival preparations were much the same; he only understood that this was the most exciting time for the townsfolk when Holo grabbed his hand.

“This is a good place; they have all sorts of grain here.”

Holo, whose hangover had finally subsided come nightfall, spoke as she sat at one of the tables outside their inn, nursing a cup of alcohol despite the previous day’s activities.

That said, she slowly sipped at it like it was a watered-down cider, so perhaps she was not totally oblivious to the lessons learned here.

“Business went well for me. I guess the townsfolk feel much lighter without any of that debt weighing them down.”

“Mm. And you sold all that fetid nonsense in the back of the cart?”

Lawrence had to use his fame somehow now that he had made something of a name for himself in town. He had managed to sell half of the mountain of sulfur powder he had brought with them when they left Nyohhira. He even thought he might be able to sell a bit more, considering how the townsfolk, in their debt-free joy, were talking about making impromptu hot springs by digging holes and filling them with hot water.

“I’ve no complaints, then,” Holo said, comfortably closing her eyes, allowing the cool evening breeze play with her bangs.

There was still time before the sun completely set, but the town did not go to sleep in the evening when the festival loomed near. As Lawrence sat hoping that Holo, who had spent most of her day napping, would not drink too much today, the innkeeper brought them food and warm soup.

“Ah, yes, there is nothing better than this after having a bit too much to drink,” she said, eagerly slurping the mushrooms and vegetables that had been boiled with the broth. “But I do have one regret.”

“Hmm?”

Holo set down her bowl of soup, instead picking up a slender, seared sardine and biting into its head.

“At least ’tis not herring. I heard that this town would typically have a rich selection of river fish to choose from.”

Herring was so abundant in the ocean that it was said a person could stab a sword into the water and pull it out skewered with the fish; one could always find it on the dinner tables of houses far inland. Not only that, it was cheap—and so it became a staple during the winter, and even those who were not as picky with food as Holo often detested it.

In contrast, fish from rivers so dark one could scarcely see any at all were often far away from the sea and the salt needed to preserve said fish, so they never went far. Good, local river fish could only be eaten in those specific places.

“I took a look at the river by the town, but it didn’t seem like there were a whole lot of fish in there. And you know what they say—the two things that will always find you away from the seashores are the moon and herring. But this is a sardine anyway.”

Lawrence bit into the fish, and a delightful bitterness filled his mouth.

He would have preferred it seared just a little more, but Holo drew up her shoulders.

“Look, you see the hazy mountain in the distance? From our room at the inn?”

“Hmm? Oh, yeah.”

As Lawrence reached out for his third sardine, wanting more of that bitterness in his mouth, Holo smacked his hand away.

“’Tis not the way we came into town, and I hear there is a mythical pond tucked away there.”

“Mythical?” Lawrence repeated, not paying too much mind as he spoke; he lifted and waved in the air the plate that once housed the sardines at the innkeeper.

“They say the most delicious trout lives there, but there is not a single one in stock in any of the stores this year, of all years.”

“Huh.”

Being the bathhouse owner that he was, Lawrence began to think of a meal he could serve with trout—it tasted great wrapped in a large tree leaf and fried with mushrooms and plenty of butter.

“They were apparently raising them especially in that pond, but then a disease struck them.”

“Rearing fish in a pond, huh? It’s not like making a preserve in a river at all; it’s much more difficult. They say everyone in Nyohhira’s tried it a few times before, but it’s never gone well.”

“And that is why all we eat is herring and sardines.”

Despite her complaints, Holo greedily munched on the sardines that Lawrence had gotten for himself.

A plump trout, of course, went well with a mug of ale.

And as a former businessman, Lawrence did have some thoughts on the matter.

“That must feel pretty bad. They must have been raising them specifically for the festival season.”

A mountain fishpond was surely a precious source of income to the locals. They might hesitate in putting even more fish in the pond after a disease had wiped the previous lot out, and he could easily foresee their troubles continuing.

As those thoughts crossed his mind, Holo’s eyes darted away, as though her gaze had been drawn elsewhere. Lawrence followed her eyes to find Elsa, giving them a small wave.

“What does she want?”

Holo’s question was thorny because she knew that once Elsa joined them at the dinner table, the woman’s scolding and lectures would accompany her.

Maybe Elsa had caught wind that Holo had ultimately knocked herself out drinking after selecting the alcohol that would be served at the festival.

“As a devout servant of God, it is ever my duty to preach moderation to you,” Elsa began, exasperation coloring her voice, as she turned her attention to Lawrence. “But my business today is with Mister Lawrence. I have a request to ask of you.”

“Of me?” he asked.

At that moment, the innkeeper brought out more seared sardines; Holo reached out not only to grab the freshly-seared sardines, but also to grab the scruff of Lawrence’s neck.

“These are mine. I will need some collateral because you will be working too hard.”

The same thing had been written in the annals, so Lawrence would not protest. He drew himself inward, just like the sardines that Holo was mercilessly decapitating with her teeth.

“You will need to provide some collateral, too.” Elsa turned to Holo.

“Hmm?”

“Wouldn’t you like to eat some delicious trout?”

Speak of the devil.

Lawrence and Holo exchanged glances before listening to what Elsa had to say.

The mountain Holo saw from the inn window was, reportedly, part of territory called the Rahden Bishopric.

It was nowhere near as vast as the Vallan Bishopric, where the pair had solved the mystery of the cursed mountain with Elsa; all it had was one small village. This remote, mountain hamlet was unusual for the area in that it ran a river-fish nursery. Their fattened trout were especially well-received, and they were considered a delicacy in Salonia, since all the townsfolk could fish from their muddy nearby river were carp. Disease had plagued the nursery for several years now, and it had been particularly bad this year—every fish had perished. Their only choice was to wait until the pond water was rejuvenated, and it would be a long time before the trout would grace Salonia’s dinner tables once again.

When Elsa finished her explanation, Lawrence guessed that she would next ask them to use their mercantile prowess to save them from the tough situation.

But with their main industry gone, it would be difficult to find something else to replace it and put money in their pockets and food on their tables. Lawrence could establish a trade empire if he could solve something like that in the blink of an eye. As those thoughts crossed his mind, he found that what Elsa had to ask of him was somewhat similar to what he was expecting, but entirely different at the same time.

“You want me to find a way to get them a loan?”

The villagers were likely troubled by the loss of their main industry, so a loan was logical.

“Would you like me to speak to a company somewhere? I’m not sure if I could…”

Loans meant a long-term relationship between lender and borrower. Anyone in their right mind would hesitate to give money to a traveler who suddenly turned up one day with haphazard excuses. And it was not long ago that Salonia had been caught in such a tangled web of debts that the town had been virtually paralyzed.

As Lawrence considered how he had just untangled said web, Elsa shook her head.

“Not at all. Companies have already turned the village down, and their only option is the Church.”

“…”

He did not respond right away because what Elsa was saying sounded so strange to him.

Even if Elsa was, quite literally, in a temporary position, she still held the post of pastor. And not only that, she had played her own part in resolving the commotion that had overtaken the town, which meant she likely had more sway than her post should have afforded her.

It was God’s will that she help those in need, so if she expressed her desire to help those people, she could likely convince the Church with ease.

“Or would you like me to investigate whether they’re able to repay any debts?”

Elsa always stood with her back perfectly straight, every strand of hair in her bun perfectly in place even after a long day of work.

Uncharacteristically, the woman seemed to hunch her shoulders slightly as she said, “No, that is not a problem. The nursery had been doing poorly for years now, but since the villagers are diligent, they have now made stable lives for themselves hunting deer and making leather string. This town is a hub of trade—no amount of leather straps to secure bags shut would ever be enough. That is why I doubt they truly need a loan after all. What I mean to ask is…” Elsa turned to Lawrence, her typically tough demeanor now colored by a hue of concern on her face. “We want you to find a way for the Church to loan money to them.”

The unease on Elsa’s face made it seem as though she was a young child trying to speak a foreign language.

It truly seemed as though she had no confidence that what she was trying to say made any sense.

“Er, I ask that you find a way—”

“No, I understand. It’ll be fine,” Lawrence replied.

It seemed as though Elsa wanted to say more, but she meekly kept her mouth shut.

But while Lawrence understood each and every word she said, he did not quite understand the sum of their meaning. After a brief silence, Holo spoke up.

“The villagers want money, no?” “And you Church people want to loan them money, no? It sounds quite fair to me.”

The look on her face told them that she was already fed up with the inevitable complications that were to come. She knew there was a catch.

Elsa placed her hand to her chest and took several deep breaths, carefully choosing her words before speaking up.

“Personally, I empathize with the reasons why the villagers are asking for money. I believe the Church should help them. However…” She turned her attention toward Lawrence, an apologetic look on her face. “However, the Church lending out money is not an agreeable thing. And we are in the midst of a storm that questions all the evil acts the Church has committed.”

She looked apologetic because she had no intention of criticizing Lawrence and Holo for such a thing.

Holo overtly turned her gaze away; that was because Col and Myuri had been sending considerable shock waves through the Church, and dust had been stirred up all over the world.

It was a good thing that all the years of wrongdoing the Church had committed were being held to account, but unfortunately, not everything about it would resolve in a peaceable manner. The Church was hypocritical—despite how much it praised asceticism, it had grown fat from all the tithes and donations it had received over the years.

And so, in recent times, anything regarding the Church and its money would be scrutinized, and anything that might seem innocent at first was often met with dubious looks.

Ultimately, the reason why things had turned out this way could very likely be because of Col.

“Well, if it is the right thing to do, then it shouldn’t be a problem for you to lend them money, right? I’m sure it won’t go against Church teachings so long as the interest rate isn’t too high.”

It was moneylenders that the Church found fault with; the scripture said that if one were to borrow a room for the night, the debt must be repaid. Theologians often interpreted this as meaning that a gesture of thanks was permissible repayment in the eyes of God.

“Tacit approval, if anything. But the priests here are hesitant—they think we may be set up as a scapegoat for something.”

Lawrence could understand that.

“They believe that any excess money loaned to them will be met with suspicion, especially since the village is not particularly troubled by money.”

“If that be the reason why you will not lend them money, then do you have a reason why you do want to? It sounds as though the ones who cultivate the fish are not troubled by a lack of coin,” Holo said, and Elsa turned to look at her.

She then directed her gaze ahead—the church had come into view.

“Or rather, could you listen to our situation with fresh ears and offer your judgments?”

She meant to say that the villagers’ pleas were as coordinated and theatrical as a storytelling.

And Elsa was an old friend who knew exactly what Holo was.

“My ears come at the cost of a refreshingly cold mug of ale.”

Holo could tell when people were lying.

Elsa’s shoulders heaved with a sigh as she made her way toward the church.

The sky had turned violet by the time they reached Salonia’s church; lanterns were now lit throughout town. Evening mass had ended, and while Lawrence initially thought the church might be completely shuttered at this point, they instead found the doors wide open and several women loitering by the entrance.

“There they are!”

The moment a plump woman noticed the trio, she pointed her finger and exclaimed. A crowd of people then shuffled out from inside the church. They all appeared rustic in their dress; it was unlikely they were from the town.

Lawrence was bewildered, and Holo looked dubiously at Elsa.

Elsa cleared her throat and raised her voice.

“I have brought the great merchant who saved Salonia! Make way, make way!”

“Oh, great merchant!”

“It’s you!”

“Thanks be to heaven!”

Elsa literally parted the sea of people, who had gathered as though a saint had appeared.

Lawrence enjoyed himself, recalling a time when he would get into fistfights over buying goods at market, but the sensitive Holo was shocked and shrunk into herself slightly in fear.

Lawrence gripped her shoulders to offer reassurance and they followed Elsa into the church.

Inside, in the nave where the altar sat, there were men sitting however they pleased throughout the pews. And it was truly in whichever manner they pleased—some were weighing wheat, and some were even sharpening their hatchets. Some had gone shirtless, mending their clothes, and one person had even brought along several goats.

“Hey! I told you, no goats inside! Go tie them up out back and come back later!”

Upon Elsa’s scolding, a man who looked much like a goat himself led the three goats out of the church.

As she stood sighing, a priest appeared from the corridor leading into the back rooms.

“Elsa, over here.”

He gestured to them, and Lawrence went along with Elsa to him. Following behind them was the crowd of all of those who had been loitering outside the church and inside the nave.

When they came to stand before what looked to be a multipurpose hall, Elsa turned around and said, “You all wait here.”

The command made the whole crowd—not unlike a flock of ducks—come to a halt, but they all began muttering among one another. Then, the slender, debonair bishop opened the door, allowing Lawrence, Holo, and Elsa inside; Elsa shut the door behind them, cutting the crowd off.

“What is going on?” Holo asked, like she had been having a nightmare in Lawrence’s arms, and one of the people sitting at the long table stood.

“I hope my people haven’t been troubling you.”

An old man with gray hair and an earnest look on his face addressed them. Lawrence surmised that he must be the mayor of the Rahden Bishopric.

“It’s all right, Mayor. Everyone is behaving themselves,” the bishop said casually; he certainly sounded like he belonged in a town flourishing from trade.

“I thank you for taking in the villagers. I did not originally intend to come with all of these people…”

“It’s not a problem. Any lamb of God is welcome to make themselves at home here.”

The bishop paid them lip service, but it was Elsa’s job to actually clean the chapel. Her face was scrunched up as though she was fighting a headache; she must have remembered the goats in the nave.

“And who might this be?”

“These two are the merchants who saved Salonia from dire straits, the ones we mentioned before.”

Now suddenly the topic of the conversation, Lawrence hurriedly conjured his best merchant’s smile.

“Ah, I see. I am honored.” The old man lowered his head politely and introduced himself, “My name is Sulto. I act as mayor for the small village in the Rahden Bishopric.”

“Kraft Lawrence. This is my wife, Holo.”

When Lawrence introduced himself in turn, a relieved smile crossed Sulto’s face, like he had come across a hometown acquaintance in a foreign land.

“I have heard stories of you, Sir Lawrence. No words can express my thanks that someone such as you has offered to help me. Thank you so much.”

Lawrence was not sure what sort of embellished stories the old man had heard of him, so he simply gave an ambiguous smile and nodded.

“Now then, how may I be of service?”

Just as he anticipated, the man who named himself Sulto was mayor of the village famous for its trout hatchery.

According to what Elsa had told them earlier, while the church itself wanted to loan them money, current affairs made the act of lending out money a tricky one for the church. Therefore, they wanted a merchant’s wisdom to find an acceptable way to offer a loan without seeming suspicious. There was good reason that the villagers had come out in force to the church.

But Lawrence had, at first, thought the village had wanted to borrow money after its hatchery industry had failed because they no longer had a way to make a living, but that did not seem to be the case. The men loitering in the nave held food that looked to have been purchased from town and owned tools that looked to be of good quality, despite their shoddy dress.

What did these villagers, who clearly led comfortable lives, want to do with the loan money, and why was the church trying to support them?

Sulto adjusted his posture under Lawrence’s gaze and said, “We would like the church to loan us money so that Lord Rahden may become a bishop.”

The first word that came to Lawrence’s mind was simony. It was the bishop who then interjected.

“That wording will cause misunderstandings, Mister Mayor.” He then turned to Lawrence and gave his own merchant-like smile. “Please, take a seat. There is a delicate situation unfolding in the Rahden Bishopric.”

This sounded fishy to Lawrence, and so he found himself glancing in Elsa’s direction. She was the ideal priest: honest and unforgiving of any crooked acts. His gaze was questioning—raising money to earn themselves a high-ranking clergyman was the very thing that would attract all the wrong kinds of attention in this day and age.

Lawrence had not done this because he was a particularly fastidious man, but because he was not fond of the idea of being made to cross a bridge he could not verify the safety of.

And surprisingly, Elsa turned to meet Lawrence’s gaze head-on.

“Just listen to what he has to say.”

Whatever it was, it was apparently perfectly valid under her ethical perspective.

Even Holo, who was also watching suspiciously, knew perfectly well what Elsa was like. She blinked, not expecting that reaction.

“…All right,” Lawrence said, nodding. “Tell me.”

Lawrence and Holo sat across from Mayor Sulto.

“Our town is situated within the Rahden Bishopric, but that is just a nickname for the area,” Sulto explained. “Lord Rahden, who developed the small, poor sliver of land within the mountains, is an upstanding practitioner of God’s teachings. He leads us—he is like a father to us villagers. We call our land the Rahden Bishopric in honor of his great deeds.”

It sounded a lot like magnificently bearded tavern owners who were sometimes referred to as lords. Lawrence recalled a small handful of areas in his travels that had bore similar naming conventions.

“Has Lord Rahden received official benefices?”

It was the bishop who answered Lawrence’s question.

“Allow me to speak on behalf of the records in Salonia.” The bishop cleared his throat, beginning his statement with an odd prelude. “I suppose it was about forty years ago—the land was donated to him by the noble family that once owned it. He had served as representative for a church that reportedly once stood in the area. That does not, however, make him a member of the clergy that has received benefices.”

Lawrence held back the grin that threatened to cross his face when the bishop said a church that reportedly once stood in the area. In translation, that meant there was a possibility that Rahden had received a donation of land while impersonating a member of the Church.

“But Lord Rahden’s act did save many people,” the bishop said, almost as though he had read Lawrence’s mind. “Forty years ago, Salonia was the front line in the war against the pagans. Our annals state that it was a time of terrible chaos. It was then that Lord Rahden appeared, built a pond in an inhospitable mountain, raised fish, and took in people displaced by the war. Our records state that the fish from the Rahden Bishopric staved off starvation when fish could no longer be caught from the corpse-polluted rivers.”

“I see.”

Lawrence could see why Elsa wanted to support them.

Sulto then spoke up, impatience in his voice.

“Our home had been consumed by the war. I was young—newly married—so I took my wife and my newborn and headed for Lord Rahden’s village, clinging to the rumors of salvation. When we finally made it to the village, we were exhausted, smoke still billowing from our singed clothes, and Lord Rahden greeted us by throwing us a net he had been weaving himself. I remember it like it was yesterday. He is a godsent man,” Sulto said, almost in prayer, grasping the Church crest that hung around his neck.

As Lawrence watched the mayor, he slowly inhaled and held his breath. The villagers had poured into the church because all of them had experienced the same past, and they had all been saved by Rahden. Not only that, the man was not an official member of the clergy despite having done so many good deeds, and Lawrence now understood why that did not seem to sit well with the villagers. They could not stand to see Rahden without the proper accolades, so they had come to Salonia.

But accepting a benefice was commonly accompanied by bribery, so it was hard to imagine that the money borrowed for the purpose of becoming a bishop would be used for anything but.

Curious to know how that was working out, Lawrence glanced at the bishop, who gave him a knowing nod in turn.

“In terms of granting him bishophood, the pope’s office has heard of Lord Rahden’s faith directly. So your apprehensions of…bribery are not an issue here.”

Lawrence turned to look at Elsa, and she nodded wordlessly as she pointed to her priest’s stole. She was married and had children, yet she had been ordained as a priest. The Church had been tremendously shorthanded in this time of change, so they were willing to grant priesthood to anyone they could find, especially capable individuals such as herself.

They had set eyes on Rahden because they likely wanted to incorporate someone who was already well-known for his faith—someone who could easily win the hearts and minds of the people.

If that were the case, then there was one thing Lawrence did not understand.

“Then what are you planning on doing with the money?”

Sulto sighed. “We were told that if Lord Rahden were to become a bishop, then he would have to go south to the pope’s office, and that might take more than a year.”

Lawrence wondered if it would be used for travel and living expenses, but he had a feeling that they could raise donations in town.

“When Lord Rahden heard that, he said he would turn down the offer. He said he cannot be away from the village for over a year, that he will not leave until the village’s hatchery has been made whole.”

The man sounded like someone who was staunch in his obligations.

Lawrence was about to nod, impressed, but he paused. “Um… But I have heard that things are going relatively well with deer hunting and related crafts.”

Surely, they could manage, even without the hatchery.

Sulto looked at Lawrence, a hint of sadness in his eyes. “You heard correctly. It’s always Lord Rahden who is helping us, so we started searching in earnest for industry that could replace the hatchery long before there had been any signs of illness among the fish. And thank God, when the Vallan Bishopric, on the other side of the mountain, started growing again, that caused many deer to appear around the village. Our livelihoods are now supported by venison, deer hides, and leather straps.”

The Vallan Bishopric had once been developed as a mine and had gone bare.

But Tanya, the squirrel spirit, had worked hard to replant the trees in the forest and life had returned to the area.

Lawrence, a former merchant who brought distant lands together, was delighted to learn of the link between these two places. He quietly reminded himself to tell Tanya what had happened.

“That is why we believe God was the one who brought this opportunity to him. This will allow him to be away and take a break from work in the village for a while, and his faith has been recognized to the point where he can be formally recognized as a bishop. We urged him to take it on. But he said no, that he cannot be away from the village while the hatchery’s future remains uncertain. Perhaps it’s because we are too inexperienced.”

“So, is this a loan to help revitalize the hatchery?”

Sulto did not nod in confirmation, nor did he deny the statement.

“We want enough money that Lord Rahden can leave the village with peace of mind.”

“…”

The mayor likely thought that revitalizing the trout hatchery was going to be difficult. Due to the nature of it being a pond, all the fish within the hatchery would be lost in an instant at the first signs of disease, so it was also likely that he thought it would be best not to rely so much on it in the future.

But Lawrence was painfully understanding of their motives. He did not even need to look at Holo to know that the villagers were only acting with Rahden’s best interests in mind.

He understood why Elsa wanted to help, and also why the Salonia church was looking for a reason to lend a hand.

On the other hand, the truth remained that he was not sure under what pretext the church should lend them money.

In truth, it would be best if they could borrow money from one of the companies in town, but if they got wind that it was so Rahden could become a bishop, then any company would rightfully think twice.

The biggest issue was the current trend: the scrutiny under which the Church existed grew harsher day by day.

And it was very likely that the amount of money they were asking for was enough to hold sway over the entire operations of the village, so that was another reason to step back.

Lending money to someone in power was a move that required courage, because there was no guarantee that they would pay the money back. Those related to the Church especially stood out; they could easily insist it was considered a donation, and the money would never be returned.

If there was anyone who could help, it would be the Church, but if records showed that the village leader became a bishop soon after receiving the money, then others would likely point out that it was corrupt money meant for bribery.

On the surface, there was every indication of something shady going on.

“Well, Mister Lawrence? All of us here at the Salonia church would like to help the people of the Rahden Bishopric in any way we can,” the bishop said, turning his attention to Lawrence. “When I asked Pastor Elsa if we might be able to secure your help in the matter, she said that you would be willing so long as there is no corruption at play.”

And then Elsa found that there was no foul play, but there was a big problem. Her diagnosis had been correct.

“By corruption, you ultimately mean…that no record should remain of the church directly lending money to the village, correct?”

“Yes. It sounds like a bad thing when you put it that way, but—”

“No, I understand. Just because facial hair is natural does not mean we should not be diligent in shaving. Ledgers are much the same.”

Elsa looked terribly troubled, as though she wasn’t sure if she should laugh or not, but the bishop smiled gleefully.

“If you would please, then, Mister Lawrence.”

“Of course. I can’t guarantee I will have a plan for you, but I am willing to help if you’re happy with what wisdom I can offer. I feel like this may be a problem that a money order could solve.”

“Ohh!”

A broad smile crossed the bishop’s face, and Sulto stood with wide eyes.

“Oh, I’m just musing aloud here. It’s not like I’ve come up with a way to fix this yet,” Lawrence hurriedly said as a disclaimer in response to their delight.

He had to make sure there was no direct line between the village and the church while still being honest about where the money was going.

There were several things a merchant could do at a time like this, but they would take a little work.

“Oh yes, of course. But you are Lawrence! The one who magicked all the debt away in town! I believe you will be able to come up with something for us, too.”

The bishop’s flattery brought a smile to Lawrence’s face.

“We must inform the rest of the villagers right away. They must be beside themselves with nerves,” Sulto said, rounding the table to firmly grasp both of Lawrence’s hands and bow to Holo.

But unease suddenly came over Lawrence as he watched the mayor. Though he had said he would take on the job, he had a feeling he was missing something.

He was not nervous about how the money would get lent—nothing as technical as that. It was as though he was missing something even more fundamental…

Though the thoughts churned in his head, he could not think of anything. With a nettled feeling in his chest, he watched as Sulto moved to exit the room.

It happened as he placed his hand on the door.

“Hmm?” Holo hummed. A moment later, they heard excited voices coming from the hallway.

Sulto curiously pressed his ear to the door and glanced back at Lawrence and Holo.

But it seemed he knew what was going on.

“The villagers sound excited. I should go quiet them right awa—”

He only managed to say that much.

“Wait!”

“Please wait!”

They heard shouting from the hall.

“Please wait, Lord Rahden!”

Lawrence’s eyes widened just as the door flung open.

“Lord Rahden?!”

Sulto was the first to speak up, and it was then that Lawrence realized what he had overlooked. He had come to learn of how the village in the Rahden Bishopric came to be, how it was faring in the present moment, Sulto and the other villagers’ motives, and their passionate feelings for Rahden.

But there was one thing that never came up.

And that was what Rahden himself thought.

“Sulto! Why did you leave me behind in the village?!”

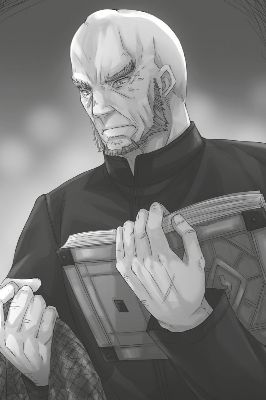

His voice was as loud as a mountain bear; he was no old hermit who spent his days in contemplation and prayer. Though his clothes resembled those of a monk, his head was shaved, and his wrinkles were so deep they seemed to be carved into his skin; he was so stout that he looked like a towering tree that had grown legs and started walking. His thick hands, the kind that were only found on those who toiled hard for years on end, were a testament to how tirelessly he had worked.

Rahden seemed much less like a fervent clergyman and more like a dutiful artisan who prioritized human feelings and relationships.

The man had complicated emotions coloring his face—ones that made him seem desperate to scream, but also desperate to cry—as he untangled himself from the villagers who tried to stop him.

“Lord Rahden! Why are you—?”

As Sulto began to speak, a young boy peeked out from beside the furious Rahden.

“Granddad! You can’t hold talks without Lord Rahden!”

“Baum! Did you bring him here?!”

“I thought it was weird that you told me to go pick mushrooms with Lord Rahden. We took your horse.”

Lawrence had completely forgotten to ask what Rahden thought of them borrowing money to give him peace of mind.

But the answer to that question was rather obvious.

“I understand you are the mayor, Sulto, but you were specifically instructed not to ask!”

“B-but, Lord Rahden! We were simply thinking of you and—”

“No, I’ve had enough of your impertinent talk! We are going back to the village, Sulto! The fishes are waiting for us!”

“Lord Rahden, please, listen! We came here because we are concerned for you and the village!”

The villagers tried to push Rahden back, but one twist of the waist and one grab of the arm had a grown man pulled into the air and tossed around like a cat.

Sulto was on the verge of tears; the boy, Baum, had raised his flag of rebellion against Sulto and the other villagers and brought Rahden to Salonia to fight alongside him.

The smooth-talking bishop was bewildered, and Holo was smiling in amusement at the sudden commotion.

What is going on? Lawrence sighed.

“Stop this at once!”

Hands slammed onto the table with a loud bang.

Everyone turned to look at Elsa—her brows knitted upward in rage.

“This is a church! A house of God! Under no circumstances will you cause a commotion in here!”

Her power was enough to make her fringe shudder; it surely came from constantly scolding three boys and a husband at home.

Rahden’s, Sulto’s and of course Baum’s eyes widened. All the villagers reacted the same.

“Do you not understand that God is always watching?! Have you no shame?!”

Her reprimand was like a lash of a whip, and all the men drew up their shoulders at once.

The only sound in the quiet hall was Holo cackling quietly.

“Father, please show Mayor Sulto and the rest of the villagers to another room.”

Sulto was about to protest, but when Elsa planted her hands on her hips and narrowed her eyes at him, he shrunk down like a little boy.

“Lord Rahden, and…young Baum. Stay here with me.”

Rahden and Baum were certainly far enough apart to be grandfather and grandson, but the way they exchanged glances made them seem like friends.

“Come on! The rest of you, get to work!”

Elsa’s command spurred the people into motion like a herd of sheep.

Sulto looked back at Rahden with regret, and though Rahden realized what was going on, he made no move to meet the man’s gaze.

The manner in which Elsa brought the drink and poured some for everyone made it clear that she had hurt her throat raising her voice that way.

Rahden struggled to squeeze his large frame into a chair and remained silent as he peered into his cup.

“My name is Kraft Lawrence,” Lawrence first introduced himself.

And as he thought, Rahden, being the frank man he was, lifted his head.

“…Rahden.”

His reply was brief.

“That’s an unusual name. Is it your family name, or…?”

“Lord Rahden’s just Lord Rahden,” the boy Baum interjected. “My name’s Baum. Sulto’s my granddad.”

Holo took a liking to the fearless Baum in the blink of an eye. She smiled with delight when he turned to Elsa and asked, “Don’t I get any wine?” and Elsa scolded him.

“So, Mister Lawrence, are you on my granddad’s side?”

The boy got straight to the point.

Though he was the mayor’s grandson, he was going against his will.

“I’m on no one’s side right now.”

“But weren’t you cozying up with the church and going to do exactly what my granddad said just now?”

“I was going to, only because he asked, but this situation seems a little more complicated than that. I want to hear what you two have to say. That’s why we had Mayor Sulto and the others leave.”

Baum stared hard at Lawrence before scoffing and looking away.

“Was the mayor trying to borrow money from the church?” Rahden finally asked, and Lawrence nodded in response.

“Was this not a unanimous decision in the village?”

“…”

Rahden fell silent, and Baum spoke up instead.

“Everyone besides Lord Rahden and people like me who are on Lord Rahden’s side agreed with borrowing money.”

Lawrence got a general sense of where things stood in the village.

“Granddad said he was coming to do business in town, but he sent me and Lord Rahden off into the mountains, and I thought that was fishy. And just as I thought, when we got back, we heard that most of the villagers had come to town.”

“That’s why you rushed here on horseback?”

“Exactly. Lord Rahden can’t ride a horse alone, you see.”

The image of Baum taking the reins and Rahden sitting behind him was a rather strange one, but it brought a slight smile to Lawrence’s face.

“Please pretend all this talk about a loan never happened,” Rahden said. “The village has never needed a loan. It will not need any in the future.”

“But Sulto said that you expressed some worries about the village’s prospects in the future. He wants to borrow money to ease your worries.”

“…”

Rahden fell silent.

“Are you worried because the hatchery isn’t doing so well?”

Rahden made no motion to confirm or deny Lawrence’s question, only stared into his cup.

“I think the hatchery didn’t succeed because of the tanning,” Baum interjected, his voice scarcely containing his annoyance. “We just need to stop tanning hides. Then we can let fish into the pond. Village goes back to normal.”

There was no doubt that the tanning process could pollute the water. Lawrence glanced over at Holo because he thought investigating whether or not the tanning process was the cause was an option.

But Rahden turned to look at Baum and said, “The tanning has nothing to do with this. The water sources are clearly separated.”

“But—”

Baum was about to argue, but Rahden’s look was enough for him to keep quiet.

“I am worried,” Rahden turned to look back at Lawrence. “The deer hunting is…not sustainable. I want to reestablish the hatchery in the village.”

His unaffected language made him sound like a tree spirit. But a being who was one with nature currently sitting beside Lawrence seemed to twitch her ears ever so slightly under her hood.

“And I am not suited to becoming a bishop.”

“Are you sure about that?” It was Elsa who spoke this time. “From what I have heard, you are more like a bishop than a great many who already wear the robes of one.”

She sounded like she was stating an obvious fact—black was black, white was white—and it was oddly convincing.

Rahden was about to say something, but he eventually decided not to.

Elsa seemed slightly annoyed with him for a moment before continuing, “I have often been asked to manage the ledgers in churches across the area. Every bishop in every church I’ve visited has an impressive work history, but none have devoted themselves to studying the scripture, and they are all careless with money. I have always thought that such people need to be removed and replaced with bishops who are truly faithful.”

Elsa’s words caused Rahden to close his eyes with a wry smile.

“I know you are staunchly faithful,” he said. “To hear that from you is a relief. It tells me that I have lived my life the way I should.”

Though appearances made him seem as though he approached every problem with brute strength, his word choice made him sound like a genuine bishop.

“I am simply being honest,” Elsa said.

Rahden’s eyes snapped open and he turned to Baum, almost as though he was trying to avoid the problem.

“Everyone is overestimating me.”

“Lord Rahden…”

There was a hint of frustration in Baum’s voice, and Rahden sighed.

“Sir Lawrence, was it? My name is Rahden. Just Rahden. I left my hometown when I was young, around Baum’s age. It’s been about forty years now. All those who knew my real name have likely departed this world by now.”

Years of hard labor outside had left their mark on his skin—giving it a particular leathery quality created by the tanning process that was sweat, dust, and the sun. Rahden’s bald head and hands were the same; he looked down at his hands as he continued.

“My home is the poor village of Rahdelli. You’ve heard of it, haven’t you?”

Lawrence found himself unconsciously holding his breath when Rahden mentioned the place.

“I have, yes, but…are you really from that far away?”

Holo turned to look up at Lawrence, her head tilted.

“Um, you remember what I told you before, right? About the nobles who drizzle honey and lemon over ice? The land of eternal summer, of the burning desert? That’s Rahdelli.”

“Ha-ha, I do remember that myth.”

In order to reach Rahdelli from Salonia, one had to head west and then take a boat from there.

It was entirely possible to travel partway on foot, but crossing the steep mountain range that blocked the way made it a life-threatening journey.

In one way or another, it would take at least three months to get there—six, in a worst-case scenario.

One would have to go to the southernmost point of the continent, and then once one encountered the warm, glittering seas there, one would have to take a boat across several islands to reach the opposite coast.

It was so far that Lawrence had only ever heard of its name.

“Rahdelli… Is that why you’re named Rahden?”

Lawrence was certain that no one would ever find anyone else from Rahdelli in this area. There was no way Rahden would ever find someone who would know his real name, which is why he had taken on the name of his homeland.

He understood that mindset after living on the road for so long.

“My village was run-down, dying. And the warm seas were full of sharks, so we could never catch enough fish. We…well, I’m not sure how you’d say it up here, but we made our living by searching for treasures in the sea. We rarely found any; maybe once a year. We were like pirates.”

Treasures that could be found in the sea were typically amber that washed up on the beach after a storm, but when Rahden said they were pirates, Lawrence wondered if he commanded a famous group or something.

“After three years with no harvest, my village fell apart. I was all alone by that point, so I felt drawn by the land across the sea and wanted to see what was beyond. I got onto a trading vessel as a rower. I was strong enough after searching for sea jewels, so they put me to good use.”

Rowing a ship was hard labor often used as punishment. That must have been what gave Rahden his physique.

“I went from ship to ship and eventually found myself in a cold land. The war between the Church and the northern pagans was at its peak then, and every boat had fervent clergy aboard. That was when I learned of God’s teachings.”

“Is that when you came to the area?” Lawrence asked.

“Hmm? Oh, yes. My master…I suppose you could call him that—I stuck right by his side and made my way to the site of the battle. But things were in a horrible state back then, and I couldn’t move past this place. I couldn’t abandon all the people I saw fleeing the very place we were headed for.”

Rahden himself had left a destroyed village, so perhaps he found it even more difficult to leave them.

“When I left my master’s side, he secured me all the privileges for the land where the village currently sits as a parting gift. He was charismatic enough to convert a bird with his sermons, so I suppose it was easy for him.”

Realizing that it was not Rahden who had obtained the land originally brought Lawrence some relief.

“I decided I was going to live out my days here. I decided I was going to make this a home for people who had lost their own homes. I vowed to give my all to this place, so I dug up a puddle that had been filled with leaves and built a pond.”

“Why a pond?”

Holo asked, almost in spite of herself.

Lawrence agreed. He also wanted to know why he had decided to build a fish hatchery.

A bashful look crossed Rahden’s face.

“Because of the first passage I memorized from the scripture. God brought one loaf of bread and one fish to a starving people. The people ripped the loaf in two and gave one half to their neighbor, and someone else ripped their fish in two and gave one half to their neighbor. And so, one loaf of bread and one fish staved off hunger for a thousand people.”

The bread-and-fish story was an allegory for loving one’s neighbor, and Rahden had very nearly taken a literal interpretation of the tale.

“One after the other, people who had escaped the fires of war drifted here, and eventually the later arrivals who came because they had heard the rumors. Even women and children could care for the fish and help expand the pond. Everyone worked together, and we harvested loads of fish every year—more than I could have ever imagined as a child.”

“Our trout is really good! Did either of you try it?”

When Baum asked, Lawrence shook his head.

“This is our first year here. We were so disappointed when we heard we couldn’t have any.”

“Oh…”

Baum was genuinely upset. Rahden smiled at him and continued his story.

“It was one thing after another, and forty years passed in the blink of an eye. So much time has passed—Sulto had been burned out of his home and arrived with a newborn in his arms; that newborn grew up and had his own child, who’s already gotten this big.”

Baum’s lip curled in embarrassment under Rahden’s tender gaze.

“I have followed God’s teachings all my life. But I have no intentions of becoming a bishop. I will protect my village, and I will die in my village. That’s all I pray for.” Rahden’s gaze lifted up to the ceiling, as though peering up to the heavens. “I wish to be buried by the pond, for plump trout to gather in the shade of the tree that will grow from my corpse. That is how I wish the village to be.” He lowered his gaze and said quietly, “That is all I want.”

There was strength in his voice despite his age, but that only served to season the tones of sadness of a man in his elder years.

Holo’s head was drooped, her hands balled into fists in her lap. Though aloof she seemed, she had the kindest heart, and these kinds of stories affected her more than anyone else Lawrence knew.

“Even if the church here lent the villagers enough money to never have to work another day in their lives?” Lawrence asked, almost jokingly, and Rahden only gave him a tired smile.

“I will not go to the pope. I have no reason to leave the village.”

Lawrence thought he saw Holo’s ears twitch beneath her hood, but she was likely more affected by the wish Rahden ultimately confessed to them.

Lawrence glanced at Holo before saying, “All right.”

Rahden studied Lawrence for a moment before silently bowing his head.

The people of the Rahden Bishopric had come to town without arranging for a place to stay ahead of time, so the bishop decided that they would be allowed to stay the night at the church. Lawrence wanted to say it was a fitting decision coming from the church, the embodiment of God’s mercy, but the bishop did not seem to be the type to sweat the details—he had likely made the decision on the fly. Elsa, who would likely be charged with keeping them under control due to her peerless work ethic, was weary.

“Things have taken an odd turn…”

When she had come to see Lawrence and Holo off, her words then had also been heavy with exhaustion.

“I’d say this is much better than uncovering the problem after talks have progressed.”

There was the stubborn Rahden, and then Sulto and the people of the village, who respected Rahden so much that they would act rashly on his behalf even if it meant going against his wishes.

This was not a logical matter, which meant there was no correct approach to the problem; Lawrence only hoped that they could settle this in a way where they could fondly look back on this in several years’ time and laugh.

“I’ll come again tomorrow.”

“Thank you. I will keep watch to make sure the Father doesn’t bring out any ale.”

The bishop was not a bad person, but it was clear that he was not a very attentive clergyman, especially since he had thrown a merchant in prison simply because he felt it was something he should do during the whole kerfuffle over debts.

“Good night, then.”

“Good night,” Elsa said, tired, and went back into the church, her shoulders slightly hunched over.

Once the moment had gone, Lawrence turned to Holo beside him.

“You’re going to be up for a little while after we get back to the inn, right?”

After choosing the whisky that would be used in the festival the night before, Holo had drunk herself silly in a drinking contest.

She did not wake up at any point in the morning, of course, and was still in poor spirits during the day; it was only when the sun began to set that she went back to normal. All she had eaten that day were sardines and a bit of soup for a snack. That, and the town was at its liveliest, what with the end of the market overlapping with the festival preparations.

The hustle and bustle of town in the late hour was even greater than it had been during the day, and most of the revelers were inebriated.

“Aye. I desire fatty meat.”

“Okay, okay.”

They entered a nearby tavern at her insistence.

Lawrence sipped his ale as he watched Holo sink her teeth into a lamb chop.

The great market was where all the agricultural products came together, so it was not just the town distillers who were showing off their wares—there were also those who used their own stills and secret techniques. What Lawrence was drinking was made of barley smoked in wood hewn from fruit trees, imparting a fruity flavor.

It was easy to drink; he had a feeling Holo could down an entire barrel if left to her own devices.

“Whose side do you think we should take?”

“Mm?”

After washing down the greasy mutton with her own ale, Holo turned to Lawrence, a thick foam mustache adorning her lip.

“I’d normally approach this like a merchant and weigh things on the scale, if it were a matter of logic.”

There was a lot of emotion involved in this disagreement between Sulto and Rahden.

“Or maybe I shouldn’t get involved at all?”

An outsider meddling in these affairs usually made things worse.

The debt plaguing the town just happened to be an issue that was easier for an outsider to solve.

That said, this particular problem did not seem as steep a hurdle, but neither was it one that they could solve themselves.

“For what reason would you want to help them?”

Holo took the clean lamb bone in hand and frantically waved down the tavern girl who was carrying around food.

“Because it’d be a waste if I didn’t.”

“Would it?”

Holo, biting into the roasted beans that had come with her lamb, looked at him with surprise.

“A merchant you’ve never seen before is selling really high-quality mutton in the market. But he doesn’t realize the quality of the meat himself, so he’s trying to sell it off cheaply to people who cook meat together in a hodgepodge at their cheap stalls.”

“What a fool! Good mutton has an herbal scent to it, and is best cooked in a bread oven or something of the sort. Meat scraps taste best boiled!”

“See? You’d want to speak up, wouldn’t you?”

Holo nodded.

“Do you mean to say this is no different?”

“Exactly. He’s reclaimed land obtained through dubious means and built such a wonderful little village. People have taken to calling him a bishop, but he’s not a man of the clergy at all. One day, however, an invitation to actually become one comes directly from the pope, and he turns that down for some reason?”

A bishop was a very high position in the clergy. It was typically a title only obtained after deep study of theology of one’s own will, mastering high-level canon law while serving at a church, then taking a slow journey up the Church’s ladder starting as assistant priest.

It was not attainable through faith alone; one needed cunning and political chops and to give plenty of gratuities to senior clergy in order to cross these barriers.

But to be given the opportunity to skip all of that and immediately become a bishop, only to turn the position down? Anyone would call that a waste.

“Perhaps he simply isn’t interested. Little Col loves the scripture, but he is not the type to swagger about a church, no?”

“I have a feeling this is a bit more than just plain old interest. If he were to become a bishop, then his village would become the formal seat of a diocese. There is real benefit to that happening, and anyone who is genuinely concerned for the village’s well-being should be able to see that.”

“Mm.”

Holo gave a halfhearted response; either she was not sure what Lawrence was getting at, or it was because she had just seen them take out a hunk of mutton from the oven in the kitchen.

“The bishop here said the same thing, but the Rahden Bishopric has rights to the land on behalf of a church that doesn’t exist. If a descendant of the former noble owner or anyone like that came in claiming the whole thing was a scam, then there would be nothing they could do to fight it.”

“I…suppose that could happen, yes.”

“But if a real bishop were in charge of the bishopric, then the Church would side with them in a tough situation like that. The noble would have to really fight if they wanted the land back in that case. It’d be the same as fighting with any other landowner.”

Just as Lawrence finished speaking, the sprightly tavern girl, her red hair tied back with a ribbon, set the plate of freshly grilled mutton on their table.

Holo asked for seconds of her drink as the tavern girl passed by before taking her knife and carving a line in the meat.

“All this is mine.”

She was putting territorial dispute into practice.

“And if the town falls into financial trouble in the future, then it would be much easier for the Salonia church to lend a hand. People rarely question when money passes between churches, nor do they think it very problematic.”

“I understand that. Back when I was naught but your traveling companion, ’twas quite painful to simply have a meal because you would always be paying. You should know how much it eases my consciousness now that I am your wife.”

“…”

Lawrence turned to her wordlessly, his lips drawn in a strained smile, and in turn she gave him a sweet-yet-sinister smile in return. She then cut into the meat with joy and bit into it.

“Well, if Rahden does become bishop, that title comes with all kinds of perks, you see. Even if the worst of the worst happens to the village, he wouldn’t need to worry nearly as much.”

After crunching her way through the cartilage, Holo spoke without bothering to wipe her mouth. “There must be disadvantages, too, no?”

Of course that was where her mind would go. She was the wisewolf.

“Of course. He’d be a part of the Church, so whoever assumes his position would be in a position higher than the mayor.”

“Mm. I can imagine this would be a particular handful of an individual.”

“I think that might be what Rahden’s worried about.”

Rahden had nurtured and developed the village up under his own personal care. He would not be very happy if an outsider came in and started acting like it was their own.

As those thoughts crossed Lawrence’s mind, he took a piece of mutton, smaller than the smallest portion Holo had cut for him, and bit into it. The sweet fats filled his mouth.

“And you noticed something while Rahden was talking, didn’t you?” Lawrence asked. Holo, who was hunched over as she munched into her mutton ribs, lifted her gaze at him with rounded eyes.

“’Twas nothing notable. He said deer hunting was unstable, so he was hoping to bring the hatchery back to the village, no?”

“Was he lying?”

Holo shrugged her slender shoulders; she stared fixedly at the stripped bone, then sunk her canines into a sinewy piece of meat that still clung to it.

“You said that his deer hunting was going well. Perhaps the fool simply dislikes the thought of it.”

The way she spoke made it sound like she was deliberately putting emotional distance between her and him. Lawrence sensed that she was not keen on touching the heart of the issue, though it did not seem to be major enough to consider her to be hiding something.

As he wondered why that was, he recalled what Rahden had said.

“Maybe Rahden built the lake in the mountains not to get rich, but because he was sentimental about the home he left behind.”

The man had said that the first passage he learned from the scripture had guided him to do so, but it was still rather unnatural to build a lake, of all things.

Holo did not respond right away; after munching on her bone with loud crunching noises, she placed it down with a sigh.

“I know not how people think.”

Her remark sounded heartless, but Lawrence knew how she felt deep inside.

She once lived in a place called Yoitsu with her friends, and she left one day on a total whim. Though she had intended to return straightaway, at the end of her wanderings she found herself overseeing the wheat harvest in a town called Pasloe by strange coincidence. She claimed she had made a promise with a villager she met there and ended up fulfilling that role for centuries out of a sense of obligation. Time passed, Holo forgot the way home, and her old friends were lost to the ravages of time. There was no one left to answer her lonesome howls.

And despite all that, Lawrence had brought up the topic of recreating a lost home.

A problem that was typically kept buried, one that was unsolvable, showed its face at times like this.

Though he understood why she would want to distance herself from the concept, there was still one thing he did not understand.

“But that doesn’t really have anything to do with becoming a bishop.”

So what did that mean?

Lawrence sat thinking, mug of ale in hand, but his thoughts didn’t lead him to a clear conclusion. In all honesty, it seemed preposterous that Rahden would turn down the position of bishop. He also could not find a sensible reason for him to be so harsh on the busybody Sulto, or for it to turn into the big scuffle it did at the church.

There had to be another reason why Rahden would refuse the position.

As those thoughts ruminated in his mind, he noticed Holo was looking at him from across the mutton with a weary look on her face.

“Hmm? Wh-what is it? What’s wrong?”

He brought his hand up to his face in surprise, wondering if something was stuck to him, then looked down at the mutton, also wondering if he had accidentally cut a piece of the fatty part for himself, which was Holo’s favorite bit.

When she saw his reaction, she sighed.

After a moment of heavy hesitation, she opened her mouth.

“Dear, I think—”

Just as she was about to continue, a loud voice cut her off.

“Well, well! If it isn’t Sir Lawrence!”

They looked up in surprise to see a man with a bald head, full beard, and round belly—Laud, the very picture of an elderly merchant. He was the owner of the company that first presented his loan bonds to them when Salonia was in an uproar over debts.

Ever since then, he had come to see Lawrence as the hero of mercantilism.

“Your wife is beautiful, as always.”

Though Holo typically was the kind to readily accept compliments like that, she only offered a vague smile in return, having been interrupted just as she was about to say something.

“You know, I heard that the church was swarmed by folk from the Rahden Bishopric, and that they called for you specifically, Sir Lawrence. That was about whether Lord Rahden is going to be a real bishop, wasn’t it?”

Everyone knew at this point since Sulto had discussed the matter with many trading companies.

“Yes… They say that the merchants in town turned down their requests for loans.”

Lawrence’s tone was teasing because he knew that Laud was one of the ones who had turned them down. Laud himself shrugged, mug filled to the brim with ale in one hand, at the implication.

“We wouldn’t have minded a small loan…but they asked for quite a bit, and you know how things have been. And if Lord Rahden was to become a real bishop, then the problems would start once someone comes to take his place. There is more than a small chance of us never getting repaid.”

Lawrence had considered that very issue; any merchant could think of at least one or two real-life examples of such a thing happening.

“But my business partners and I agree that it would be a good thing if it were to become a real bishopric. When I saw you, I had to find out what you think.”

“I don’t think this will be quite what you’re expecting, but…”

Laud took a sip of his drink and gave a sympathetic smile. “Lord Rahden himself doesn’t sound too enthused about the idea, does he?”

It sounded as though he knew that already.

“Why do you think that is?” Lawrence asked.

The outer edges of Laud’s eyes, red from the alcohol, drooped as he replied, “Hmm… You know, I find that strange, too. Speaking logically, being made bishop is like being a country girl that a prince wants to marry. I know it’d be a lot of work, but if someone’s inviting you to take the throne, you’d take it, wouldn’t you?”

Lawrence laughed in spite of himself, but the metaphor was indeed accurate.

“Well, he’d have to leave the village for a while if he became bishop. I bet it’s because that hatchery of his isn’t going so well. The mayor and all of them are busy with deer hunting and all those products, so Lord Rahden must think he’s the only one who can do it.”

When Lawrence had asked if Sulto was going to revive the hatchery with the loan, the mayor had given an evasive answer.

He must have thought that putting money and effort into a difficult-to-maintain hatchery while the deer business was going well was not the best course of action.

“And Lord Rahden set up that whole pond because he wanted to re-create the ideal seas from his hometown, didn’t he?”

“So that is the reason why, isn’t it?”

It had been nothing more than their own speculation before this conversation, so Lawrence latched on to what Laud said.

“Obviously. Better if there was a nice pond out there to begin with, but he went through all the trouble to dig a hole and fill it with water. Tugs at the heartstrings, doesn’t it? The mayor and his friends should help him out, I say, even if it doesn’t make them a fortune.” Laud sounded disappointed. “All that fatty fish was so tasty, too,” he murmured; that was likely how he genuinely felt.

But something about the pond and Rahden re-creating his ideal hometown did not quite add up in Lawrence’s mind.

“But didn’t his dreams come true already?”

“Hmm?” Laud hummed in reply.

“I hear it’s written in Salonia’s annals—the fish were so abundant one year that it saved Salonia from famine.”

“Oh, yes, that was back when I was a snot-nosed brat. I remember. It was the tastiest trout in all the world.”

Which then begged the question: Why was Rahden still so attached to it?

“By the way, the mayor and the others didn’t say anything about filling up the lake, did they?”

It was a worry of all men who worked away from home that something would happen to their secret savings while they were gone.

When Laud heard the possibility, he howled with laughter.

“Ha! Who’d be so stupid? If the bishop were to give up on the hatchery, then they’d use that water for tanning, anyway! I’d say the mayor and his friends would only deepen their faith in it, thinking since Lord Rahden made it, it might even be a miracle spring that could save them twice!”

When he put it that way, he was likely right. Though it was not the same picturesque ocean from the man’s hometown, it was still put to good use for the villagers.

Rahden would be gone for just one year to get the formalities done that would make him a bishop. And judging by the way Laud spoke about it, it was hard to imagine Sulto and the others turning the pond into a tanning workshop while Rahden was away.

In that case, Rahden should be fully able to return from becoming a bishop and get back to reestablishing the hatchery.

As Lawrence hummed in thought, Laud suddenly thrust his face toward Lawrence’s, a teasing remark accompanied by breath that stunk of alcohol.

“The lads and I think that Lord Rahden might be close to realizing a second dream of his.”

“What?”