TAIL RONDO AND WOLF

Late that night, Lawrence suddenly awoke in a chill. Half-asleep, he pulled the blanket up to his shoulders and began to search around inside of it—something was missing. There should have been some fluffy fur of a very different make than the blanket.

What’s more, it was the genuine fur of a living creature that emanated its own body heat, and there was nothing warmer than pulling both the fur and its owner deep into his arms. The only flaw was the fact that the fur’s owner was a terrible sleeper, but so long as she did not headbutt him, Lawrence was confident he could sleep soundly until morning, even in the dead of winter.

No matter how long he groped around in the dark, however, he could not find what he was looking for in the blanket. Had she gone to drink some water outside, he wondered, cracking his eyes open, and that was when he realized what it was.

Holo had left the night three days prior.

With nowhere for his hands to go, he placed them on his chest. From the gaps in the windows, the moonlight streamed onto the ceiling, drawing streaks like a beast’s claw marks. Dawn was still far off.

He rubbed his face with his hands and let out a small sigh.

That first night had been so much easier alone.

Ever since they left their bathhouse in Nyohhira to go on a journey, Holo had steadily began to drink more and more alcohol, either because of the feeling of freedom traveling offered her or because she no longer had a need to act like a dignified adult before her daughter. She liked to let the buzz put her to sleep, so he constantly had to take care of this and that before going to bed himself. Of course, Lawrence did not hate these duties of his, and Holo probably was only partially pretending to be drunk, fully enjoying being pampered, but it was still a hassle all the same.

That was why he thoroughly appreciated his first calm night in a long while with a sigh of relief.

On the second night, he found himself restless with nothing to do.

Lawrence was staying at the lodging quarters in the cathedral of the Vallan Bishopric. The one looking after the place was a female priest who was an old acquaintance of his named Elsa, and she was not the sort to while away the long hours of the night with drink and chatter. She would finish eating her simple dinner before sundown, offer a long prayer to God afterward, then soon hurry off to bed so as not to waste any candles. The one thing she said before bed was, “May tomorrow be another quiet day.”

Holo was the exact opposite—she cherished feasts and any opportunity she had to drink. “We traveled a lot today, so let us drink; absolutely nothing happened today, so let us drink; and we cannot let the day end so early, so let us keep the candles lit.”

Even before she let her tipsiness lull her into sleep, she would often mumble about what might be on the menu for the following day’s breakfast.

It was normal for him to spend nights with her like that, so to be sent to bed so early left him feeling restless and idle, as though he still had things to take care of and energy to spare. Though he eventually caved and took out the drink, it felt strange to have it by himself, so he gave up on that as well and had no choice but to simply sleep early.

On the third night, Tanya came down from the mountain. She was the embodiment of a squirrel who took on an important role in the myth of the angel of the cursed mountain, passed down through the Vallan Bishopric. It was only a few days ago that Lawrence both figured out the secret left behind in the mountain and solved the alchemists’ mystery; ever since, Tanya looked at him with glittering eyes, which embarrassed him a little.

The thing she had been focusing all her energy on these past few days was drafting up a plan that would establish the sites for timber cutting and charcoal burning on the old mining—and now “cursed”—mountain. Holo had left three days prior for exactly that same reason—she was delivering a letter that proposed selling the mountain to their old acquaintances at the Debau Company. It would not take long for the mountain to go bare again if it simply reopened as a mine, so they proposed that the company buy the land primarily for timber and charcoal burning.

Tanya, who had spent many long years bringing greenery back to the barren mountain, was fervently drawing up a plan that would allow the greatest possible profit while keeping the mountain’s lush foliage in place.

And so she feverishly begged Lawrence for answers to questions like what types of trees did she need to grow or what age tree sold for the most money. The girl, normally round as a ball when she was in her squirrel form, was mild mannered and as absentminded as she looked, but she could also be surprisingly tenacious and determined. Moreover, she regarded him as a hero, which he found to be incredibly moving as he offered her his thoughts.

She was entirely different from Holo, who would never remember the types of coins no matter how many times she was taught, who was smart but grew bored quickly, who enjoyed herself the most whenever she was mischievously play-biting him. And that was to say nothing when compared to his daughter, Myuri, who inherited a great deal of Holo’s blood and boasted a youthful tomboyishness on top of that…With a sigh for what could’ve been, Lawrence readily counseled the passionate Tanya.

Since this had to do with the bishopric’s assets, Elsa also joined in on the night of the third day, staying up late for the first time in a while, but when everything was done and they returned to their rooms, the silence and darkness felt that much heavier. Lawrence had not felt this way since his time as a traveling merchant. It felt the same as returning by himself to his empty room in an inn to prepare for the next day after participating in a festival that he happened upon by coincidence in a village on his peddling route.

Then the fourth day came.

During the day, he spent almost every waking moment with Tanya, who had spent the night prior, polishing the afforestation plans for the mountain, but once the sun set she returned to her beloved mountain, and Elsa went to sleep early as always. Lawrence, alone, knew it was tasteless, but he could not keep himself from pulling out the alcohol.

He poured himself a little more than normal and took a sip, had a bite of his sausage, then helped himself to another sip. This repeated quickly as he had no one to talk to between drinks, and before long, he was quite inebriated. Once that came over him, he dove into bed as though he was leaping off the back of a galloping horse.

However, even with the influence of alcohol, he still could not get to sleep and ended up tossing and turning. Then, just as he thought he had finally managed to slip into slumber, he sobered up with a chill that startled him awake, which brings us to the present.

Lawrence did not want to acknowledge it.

He was lonely.

He could scarcely remember what life was like before he met Holo, and it was much too cold in the blanket despite it not being winter.

The Debau Company was certainly far, but Holo’s legs could take her there in an instant, and he knew it was next to impossible for her to become lost or get in an accident or even fall prey to bandits.

In which case, she was either disputing the sale of the mountain at the company, or what was even more likely was that she had been greeted with a warm welcome at the main branch of the flourishing Debau Company and was extending her stay as long as possible. He could easily imagine her enjoying a bit of drink and meat.

Though he knew there was little he loved more than Holo enjoying herself, Lawrence nonetheless found himself spending cold nights here all alone. Something was slowly bubbling beneath the surface.

In his bed, he heaved a deep sigh, gave up on sleep, and sat himself up. Relying on the light of the moon that filtered through the gaps in the window, his eyes darted about, and the thick bundle of paper on the table caught his attention.

He got out from his bed and reached out for the paper, flipped through the first few pages, and in inimitable script, one he could not even say was good out of flattery, was a record of what happened day to day.

It contained thoughts like, The bread at breakfast was hard. There was not much meat in the porridge for lunch. The evening wine was sour.

“This is all about food,” Lawrence murmured with a wry smile, reading through Holo’s diary. She had just listed a whole mountain of inconsequential items after another, but those were daily memories that would easily be forgotten when one spent their time normally and that was exactly what Holo wanted to record, so she had written it in her diary.

What surprised him was how much he could recall when it was all written down like this.

He stood, flipping through the diary, and finally sighed as he brushed some of the writing. This was essentially medicine for the long-lived Holo, prepared on a daily basis for the day she would inevitably have to part with him.

Of course, Lawrence thought he had grasped what that meant. But now that he was left by himself in this room, for the first time he truly felt and understood a taste of what it was that Holo would have to battle with in the years to come.

He had only been apart from her for a few days, and he was already a mess. And that was despite believing that in the near future, she would be coming back to him.

But what if this was an eternal parting? If they would never see each other again?

Lawrence took a slow, deep breath and shook his head. That would be pain he could scarcely even imagine. That was what was waiting for Holo.

There were only so many things he could do, but he could at least let this diary grow thick and let her have as much as she asked for—as much as he could possibly give her…That was what occurred to him at first, but those feelings slowly deflated.

That was because as he read through her writing, as though he was chasing her tail, he found nothing but complaints like, Lawrence did not buy that for me; he did not do this for me; he is inconsiderate; he snores too loud, despite how much he took care of her.

“I feel like I might be spoiling her too much, just like Miss Elsa said…”

Lawrence flipped through and looked at her most recent entry, the one she wrote the night before she left. All it said was, There most certainly will be loads of delicious drink.

Suspicion toward Holo and her late return reared its head again.

The Debau Company was a massive conglomerate that held incredible sway over the northlands, and they had control over a good portion of trade. She was certainly not wrong to expect them to offer a near endless array of delicious treats, and her hard work for delivering the letter was deserving of praise, no question.

But to Lawrence, who was left sipping on flavorless drink, it felt somewhat unfair.

He sulked, imagining Holo enjoying herself without him.

“Hmm?”

A shadow suddenly passed over the moonlight outside. If it was a cloud, then it was strange that there still seemed to be light filtering in through a different window.

He wondered what it was and opened the wooden shutters; the reason he did not give out a cry was not because he had iron nerves.

It was because the sight that greeted him was so far removed from reality.

“What, you are awake at this time of night? Too lonely to sleep?”

Under the moonlight, a massive wolf gave a mischievous grin.

Though his lodgings were on the second floor, the window was right at the height of Holo’s nose in her wolf form.

Lawrence stood still without saying a word, wondering if it must be a dream, when Holo’s tail swished back and forth before she stuck her nose into the window.

She sniffed, and this time pressed her large eye up to the window.

“You have been getting along quite well with that squirrel, no?”

The large eyeball, too big to fit into Lawrence’s arms, glared at him.

Holo’s red eyes could spot even the most minute twitch of her prey, and her wolf ears could pierce through any lie.

Even if it was a dream, Lawrence was so happy to see Holo that his face almost broke out into a smile on reflex, but he resisted mightily, took a deep breath, and responded, “We had to talk about a great deal concerning the mountain.”

“And yet, you have been close enough for her smell to cling to you like this—what were you scheming?”

Tanya was mild mannered and sociable, which made her wholly unlike Holo and the pessimistic air she normally projected.

He would not deny that they had been in close contact, but Holo’s suspicions of adultery were unfounded.

First, Lawrence also had something to say.

“If you were so worried about your prey, then why not come back a little earlier?”

Holo blinked, surprised to be met with a counterattack, then wrinkled her nose.

“Fool. How many miles do you think I have covered at full speed?”

She growled from the other side of the window.

“You smell a lot like alcohol for someone who’s supposedly been running this whole time.”

Despite how her whole face was covered in fur when she was in her wolf form, her expressions were surprisingly easy for him to read.

She turned away, as though trying to gloss over that, so Lawrence could tell right away she had certainly drank her fill and perhaps a little more at the Debau Company.

She did not seem drunk, of course, so she had likely only sampled enough for the smell to stick to her fur.

“You fool. The rabbit simply knows how to pay his respects to the wisewolf,” Holo said, then stuck her neck against the window frame. Her rough hairs poked into the room, and there he spotted something wrapped around her neck.

“I feel I’ve been infested with fleas and am uneasy. Hurry and take it.”

Lawrence took the letters strapped to her fur and smoothed out the kinks they had left with his hand.

Like a fawning dog, Holo pushed her neck back up against him, but the walls started making an ominous creaking sound, so he pushed her away.

“Sheesh.”

Holo stepped back and grinned; then after a big twirl of her tail, she vanished.

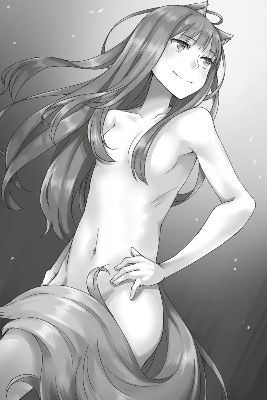

For a moment, he almost feared it was all a flash of a dream, but then he found the letters remained in his hands. He poked his head out of the window and looked down to see Holo, now in her human form, standing beneath him.

She of course wore no clothes, her pearl-like skin glowing under the moonlight. Her hair, more delicate than the finest silk, swayed gently behind her. She looked just like a spirit of the moon as she quietly peered up at the white orb hanging in the heavens.

Right as Lawrence found himself enchanted by her mystique, the beautiful wolf girl gave a loud sneeze like an old man. It didn’t do the mood any favors, but that was a part of what made Holo, Holo.

With a wry smile, Lawrence grabbed the coat draped over the back of the chair, balled it up, and tossed it down to her.

“Hurry and come on up. You’ll get sick.”

Holo deftly caught the coat, whipped it open, and wrapped it around her shoulders.

She then gathered it in front of her face and inhaled deeply.

“Heh. It smells like you.”

Her reddish eyes smiled in delight.

Lawrence wanted to say something, but he fell silent instead.

How he felt about Holo could not be expressed in a single word.

And so he rubbed his nose and simply said, “Welcome back.”

Holo’s eyes widened blankly for a moment before she smiled gleefully.

“Aye.”

What, no “I’m back”? Lawrence smiled in exasperation, and Holo lifted her chin in a dignified manner and walked off.

He watched her tail poking out from beneath the coat, and just as she vanished around the corner of the building, he went to close the window when his gaze drifted upward.

Though the moon was not full, it still shone brilliantly.

Lawrence reverently bowed his head to the moon before pulling the window shut with both hands.

It was right afterward that Holo gracefully stepped into the room, and Lawrence pulled her into a tight hug.

The following morning, Lawrence woke up and enjoyed Holo’s sleeping face for a while before gently waking her, respectfully presenting her a meal of cheese and sausage stuck into some bread, and while the princess sat on the bed, kicking her feet and stuffing her face with the bread, he cared for her tail.

Though Holo was normally quite content to let Lawrence handle all the hard work, it was only when she was in a good mood that she allowed him to take care of her tail. Even having him wipe the crumbs that stuck to the corners of her mouth after they were finished eating was part of their usual ritual.

The morning sun bathed Holo in warm light as she smiled blissfully and kissed Lawrence on the cheek.

“My own household feels like it’s in discord when I watch you two,” Elsa said in exasperation when she saw Lawrence and Holo emerge from the lodgings, hand in hand, while she went around watering the herbs growing on the cathedral grounds.

“’Tis a difference in dignity,” Holo boldly claimed, and it seemed that even Elsa could not help but smile.

“How did things go?”

“I don’t think the price was all that terrible.”

Lawrence presented the letters that Holo brought back from the Debau Company, but Elsa’s hands were soiled from her fieldwork. Lawrence took the letters back, and Elsa looked around at the herb garden.

“I’m just finished watering the garden, so why don’t we look over the letters as we eat breakfast? Or have you already eaten?”

“Oh, in that case—”

“Aye, a splendid idea.”

Since Holo had cut Lawrence’s reply off with her own words, Elsa seemed to get a general idea of what was going on.

“I will praise you for not outright lying with a claim that you had yet to eat at all.”

After washing her hands with water reserved in the nearby wooden pail, Elsa pulled out a cloth from her waist to dry them with a practiced motion, then tossed out the rest of the water and held the pail under her arm with the rest of her gardening tools.

“God commends hospitality, after all.”

Holo wagged her tail, and Lawrence went to help bring some of Elsa’s tools inside.

What Elsa brought out along with freshly boiled goat’s milk was a type of hard-baked bread that Lawrence had told Elsa’s village about and was still a specialty there—cookies.

“Mmm, this has a lovely texture.”

Holo made crunch, crunch sounds as she ate. Soft and flaky cookies were generally popular, but the harder ones had been growing in popularity recently. Lawrence also suspected that the reason Elsa expressly offered the harder type was because watching Holo eat them reminded her of a dog chewing on bones. Meanwhile, he soaked his cookies in milk before having some. Lawrence was surprised—for someone who always preached simplicity and frugality, Elsa had certainly splurged on something that used butter, salt, eggs, and most luxuriously, sugar.

“This Mr. Hilde is the one I met at your wedding, isn’t he?” Elsa remarked as she unfolded the letter addressed to her.

It had been a lively wedding, where Lawrence and Holo managed to invite most everyone they had met along their journey.

“Yes, the rabbit avatar.”

Elsa nodded, then turned to look at Holo, who was gleefully munching on the hard cookie.

“Are you certain you did not threaten him?”

Holo’s ears perked up, then she turned a grumpy eye to Elsa.

“Fool. I have done no such thing. Well, perhaps the rabbit felt intimidated by my majesty of his own accord.”

She puffed out her chest in pride, but Hilde was not that fragile, and Holo knew that as well.

“He did ask me an exhausting amount of questions about the state of the mountain and wanted to know every little detail about the angel gate on top of that. He made me speak so much that it was a pain just keeping my throat quenched.”

Though Holo may have occupied herself by drinking as much as she talked, Hilde and his cohorts had done careful calculations on the value of both the mountain and the angel gate and offered them a price.

Additionally, the angel gate was a tool created by the alchemists and their technological prowess—a metallic mirror that could concentrate sunlight to create incredible heat. It was relatively common knowledge that glass treasures meant for making text larger and clearer could sometimes cause things to catch fire, but Lawrence had no idea that it was possible to create one that could produce enough heat to refine metal by simply hammering out a sheet of metal plate to a precise degree.

Much like how a wolf could become a god if it were big enough, once the mundane crossed a certain threshold in size and scale, it transformed into something wholly unknown and alien.

“So this means our result includes all sorts of things.”

Elsa, the ideal priestess who was endowed with both education and faith, nodded quietly.

“I don’t think it’s all that bad of a price. Timber prices may be going up, I doubt they will go down that easily, so I believe the price of the mountain will hold its value for at least a while.”

“All that’s left is to guarantee Tanya’s identity here.”

Even if they did manage to sell the mountain to the Debau Company, the ones who would be actually working there would be a good number of locals. Their only knowledge of nonhumans was in the realm of fairy tales and myths, so of course revealing Tanya’s true form as a squirrel avatar to them was not an option. In order for Tanya to work well with them, they would have to arrange a plan that would allow her to conform to the human world.

On that point, the Church, who managed people’s lives from birth to the grave, could easily create an identity for a new villager out of thin air.

“I’m glad this has reached an excellent conclusion.”

Elsa placed the letters down, then looked to Lawrence and smiled with relief. Her smile was stern, but there was also a kindness to it. When she was younger, Elsa only ever showed the stern part of her; it seemed she was aging quite gracefully.

“Though it is now that things will grow troublesome.”

It was Holo who interjected, baring her fangs to threaten Lawrence as he reached for the last cookie in the wooden bowl.

“Troublesome? Why is that?”

Holo, her cheeks stuffed with the last cookie, licked her fingers in pure delight before answering.

“I will again have to take the response to that letter and head north, no? And that is quite the sum of money written there. I travel everywhere with this fool, you see. I can generally imagine how many coins that would be. If such an amount must be carried so far away, then who is it who will be taking on that role?”

Evidently already fed up with the prospect, Holo leaned back in her chair with a look that suggested she could not be bothered.

Elsa blinked, then looked to Lawrence.

Holo noticed their looks and stared hard at the both of them.

“What is that face supposed to mean?”

After a moment of worried thought, Elsa slid a piece of parchment from her side over the long table toward Lawrence, as though telling him to take care of it. With no other choice, Lawrence took the sheet and responded.

“There won’t be any need for you to carry a mound of coins on your back.”

Holo raised an eyebrow.

“Then what? Will you line up carts and fill the beds with mountains of coin?”

“We don’t have to do that, and you don’t have to send a response to the letter, either. Mr. Hilde trusts us.”

“…Hrm?”

“Even though he’s buying a mountain in a faraway place that he’s never seen for such a high price, he paid us without a second thought. He sure is the paragon of a great merchant, isn’t he?”

“What is this?”

Holo had her brows drawn together grumpily, and Lawrence said, “It’s a money order. You must’ve seen some a couple of times back when we traveled together.”

“?”

“This single piece of paper is used in the stead of massive amounts of coin.”

Holo’s eyes widened slightly, then looked at the money order with a grouchy expression.

“…Your typical magic, then.”

“I’m reluctant to talk about magic in front of Miss Elsa.”

Elsa, of course, did not deign to engage with each and every joking remark. In this case, she contented herself with elegantly sipping her goat’s milk.

“Like you said, carrying money is a hassle, and it can be dangerous, too. So instead, Mr. Hilde signed this piece of paper, which guarantees us the amount written here. And so just by taking this piece of paper to the appropriate company, we can withdraw the amount of money that’s written here. Incredible, isn’t it?”

It was the merchants’ chain of trust. The currency called trust circulated between distant, sometimes wholly unrelated companies along the latticework that was mutual trade. A simple piece of paper did the job of a pile of shiny gold coins.

The reason why misers who hoarded mountains of coin in their houses were considered the symbol of mean-spirited folk who trusted no one had been illustrated right here.

Those who earned trust and put their trust in others had no need to hide their gold in the floorboards.

“Of course, what makes it greater than magic is how Mr. Hilde, with all the trust he has at his fingertips, is so bighearted as a merchant.”

The Debau Company was a massive corporation that effectively reigned over the northlands, and they even had their own currency.

Lawrence even felt pride in the good luck that led them to meeting Hilde.

Holo the wolf, however, apparently found Lawrence’s praise of Hilde the rabbit unpleasant, so she seemed rather displeased.

“And so, unfortunately, you’ve lost your excuse to binge drink at the Debau Company.”

When Lawrence said that, Holo pursed her lips while the hair on her ears and tail stood on end.

“Fool!”

Then again, she did make a disappointed face, so perhaps she had actually been looking forward to that.

She sure is greedy. Lawrence smiled as he tried his best to console her. “No need to be upset. Either way, the talks are settled. It might be time for us to leave and head on to the next town, right?”

Holo squished Lawrence’s foot under the long table and stared at him with doubt.

“Don’t you want to drop by the grand market on the other side of the mountain? I’m still worried about Col and Myuri, but…Well, we can’t come all this way and not see the fair, right?”

Holo’s wolf ears nimbly flicked twice; then she stopped squishing his foot and immediately broke into a smile.

How calculating of her, Lawrence thought with exasperation when Elsa spoke up.

“In that case, may I make a request?” The typically calm Elsa neatly folded Hilde’s letter and boldly asked, “Could you take me along with you?”

This took Lawrence by surprise because as far as he knew, Elsa was supposed to be watching over the church while everyone else was away. More to the point, he simply could not imagine her casually shopping at a market.

Elsa then sighed and placed a hand to her right cheek, almost as though her tooth hurt.

“It turns out that some people from this church and village have gotten wrapped up in some trouble at the grand market. A letter requesting help arrived yesterday, and I wasn’t so sure what to do…But now I am certain this is God’s will. It would be most reassuring if you allowed me to join you on the road.” Elsa spoke in an almost deliberately priestly manner as she gazed at Lawrence and Holo.

What made her such a first-class priest was how she so deftly saddled others with a strong sense of responsibility.

Elsa knew exactly what her role was.

Lawrence found the clear solution comforting, so he responded with a smile.

“If you’re okay with us, then we’ll help you.”

Elsa was convinced that she would get a response like that and likely brought it up right at this moment precisely because of that.

Holo turned to Lawrence with an expression that suggested she found it all bothersome, but she said nothing.

She of course seemed to understand that the sweet and wonderfully crunchy cookies that had been brought to the table were the opening jab meant to make her more pliable before driving home this request. Holo could hardly protest as the culprit who had devoured every last morsel.

“What a great help. May God guide you.”

That is what Elsa said, even though Holo could certainly live a healthy and powerful life without God’s guidance.

When Elsa explained the situation to them, it sounded like the typical circumstances of most who paid the grand market a visit.

The residents of the Vallan Bishopric needed to sell their autumn harvest at the fair; they then used the proceeds to buy supplies that would last until next spring. While it sounded like this was a regular occurrence, the company that acted as their trade representative every year had apparently found itself in dire straits.

If this company were to go bankrupt, then the villagers would not be able to get any money from the sale of their crops, nor would they have a chance to obtain any of the goods needed to face the coming winter. If that happened, grave problems might arise in poor households that did not have any reserves to spare. Thus, the request to bring a catalog of the church’s assets to the fair posthaste.

As expected of Elsa, she did not panic in the face of an unexpected dilemma and try to leave it all in Lawrence’s hands.

“To either save a weakened animal or abandon it to better your own chances of survival—that fool certainly knows better than I first assumed.”

As they packed up their things in their room, Holo remarked, impressed.

Elsa’s conversation with Lawrence had not been to seek advice on what she should do.

In their possession was the money order, which represented the full value of the mountain they had sold. With it, they could help turn around the company’s financial situation and possibly help them out of a tough spot. That said, they had no way of knowing if that could be accomplished. In fact, it was entirely plausible that even after pouring in all the money they received from the land sale, the company might still turn out to be unsavable in the end.

On the other hand, if they ignored the company’s plight and used the money order for the people of the bishopric, they would undoubtedly be able to purchase a few years’ worth of goods.

In a situation like this, there was likely nobody besides God who could save both the company and the people of the bishopric without fail.

Elsa understood that the number of things that strength and compassion could accomplish were limited.

That was why she asked Lawrence to get a clear idea on the company’s current situation, since she would be making the final decision.

From a long-term perspective, helping the company would indebt them to the villagers, which would benefit the residents of the bishopric. However, if they were to prioritize certainty, then they should spend the sale’s proceeds on the people themselves. Elsa tackled the choice realistically and needed an objective source of information. Lawrence thought that Holo might be angry that her companion was being pushed about like this, but she seemed to appreciate Elsa’s way of thinking.

Holo had once been revered as a god long ago, so she likely had been pressured to make similar decisions many times over the years.

“But from what I hear about the company, it sounds less like they failed at business and more like some other reason.”

As Lawrence put all their things together, he handed his wife her diary. Holo, who seemed as though she would refuse to carry anything heavier than bread, made a sole exception for that diary and carefully tucked it away.

“Can they go under from anything besides failing at trade?”

“There are lots of reasons a company might be forced to close shop.”

“Oh?”

Holo seemed to have no intentions to help pack as she sat cross-legged on the bed, opening her diary and taking a quill in hand. She must have wanted to write down Lawrence’s explanation if it proved to be interesting.

He was not going to start complaining after all this time, so he continued without remark.

“The first case is they just took on too many losses. There’s also the possibility there’s discord within the company itself, leaving them unable to do business. Or it could be an issue where the permits necessary to do trade are taken away and they can’t work at all.”

Holo stroked her chin with the feather on the quill. Apparently, none of this was interesting enough to deserve a spot in her diary.

“It could also be a case where they make enough money and steady profits but still end up going bankrupt.”

Holo’s ears perked up. That seemed to stir her curiosity.

“How so? A shop making money would not shut down.”

“You’d think so, right? But in trade, it’s normal for there to be a gap in time between paying and receiving money. If it turns out that you’ll get the money from selling something next week, even though you need the coin to buy something now, there will be a time when the reserves are empty. If your coffers are empty right when important bills come up one after another and time runs out, that can be it.”

Lawrence pulled the hemp sack shut, like he was snuffing the life out of it.

“Being unable to keep promises is fatal for a merchant. End of the road.”

Holo sat cross-legged, hunched over, and wore a hard expression. She did not quite seem to buy this.

“But they are making profits, no? I still do not understand.”

“On paper, they are. That’s why they call money not received for a sold product accounts receivable or credit, but if they can get all of what they ‘lend’ back, then they can pay back everything they ‘borrowed.’ You follow so far?”

“Hrm…aye.”

“Every company has more lent out than borrowed. Basically, they’re making money. But like I said before, since there’s a gap in time between when money is paid and when it’s received, they need to be careful that the reserves don’t go empty in the meantime. Someone in the company is supposed to be aware of all the transactions and regulates the timing very carefully so money doesn’t run out, but sudden accidents and mistakes can happen at any time. Like something you did because you thought it nice enough at the time, but it only ends up souring the mood of a selfish princess or something, you know,” Lawrence explained, and Holo nodded with an I-know-how-it-is look that said, “Indeed, exactly like that fool Myuri.”

Lawrence smiled, opting not to point out the other obvious interpretation, and continued. “So the problem in an emergency is that from the outside, it’s hard to tell if the company’s lending and borrowing actually do balance out. What they have written in their account books is nothing but text in the end, and it’s not realistic to investigate every single thread.”

“Mm-hmm…That is certainly true. And?”

Holo was listening to Lawrence with what had to be keen interest, and that made him happy.

“A company has to be trusted if they intend to last. However, in order to prove that they’re making money and doing fine, it’s critical to make their payments on time every day. That’s why it’s so bad if a pay deadline comes up and there’s no money in the bank. If they can’t make their payment, then trust in them as an organization will plummet. Other people will think, Well, that’s no good, and stop selling them any products, which will delay transactions. That in turn will make payment more and more difficult, and trade will grind to a complete halt. Like a heart stopping.” Lawrence took Holo’s jacket, which was slung over the back of the chair, and tossed it to her. “Basically, it’s like a princess who’s always had everything paid for her entire life but never said thanks, and everyone else’s compassion for her eventually running out.”

“Wha—? Hey!”

“Of course, even if you figured you were going to eventually pay your debts back, that’s only in the account books in your mind. I never get rewarded, so my heart goes bankrupt. Good lesson, right?”

Lawrence smiled, and Holo drew up her shoulders and pouted before baring her fangs.

“You fool! I am the one with more lent out!”

“Sure, sure.”

Lawrence casually brushed off the indignant Holo and hauled their things onto his back.

“Trade in reality is a lot like you and me right now. Except there’s far more people involved. Imagine ten of me and ten of you, all living under the same roof, arguing about who owes what to whom. You can imagine something will inevitably get out of hand one day, right?”

“…”

Holo must have already pictured the situation, because though she flicked her tail with irregularity like a nervous cat, she did not argue with him. That was because even with just the two of them, they would argue over whether there was too much or too little jerky for dinner.

“Well, whatever the reason, it would be nice if we could help the company, but I don’t know…Miss Elsa herself doesn’t seem to have much hope, but that actually helps keep us focused. It really is fantastic how she is so pious but realistic at the same time.”

“Hmph.”

It was as though Holo was saying, That matters not, as she stepped off the bed and slung her coat over her shoulders, and Lawrence did the tie on her chest. Holo gave no thanks and wore a calm, distant expression, but her tail was clearly happy. That was Lawrence’s one weakness, which was why he always wanted to take care of her.

Holo did not often pay back what she owed, but she did pay a lot of interest.

“There is something strange about what you just said, however,” Holo said after she fiddled with the string tied in a bow at her chest. “Should that company go under, what would happen to all the loans they had given out? Do they disappear like smoke? Where would the money the folks here are supposed to receive from that company, for example, go?”

“They don’t call you the wisewolf for nothing, huh?” Lawrence rustled Holo’s hair, and she growled at him, baring a fang for having been treated like a child. “Even if a company goes under, that doesn’t mean all their assets and debts vanish into thin air. It’s likely some valuables will still be left in their reserves. That’s why there’s actually a much better way to secure money for the people of the bishopric.”

Holo noticed Lawrence’s change in tone of voice, and her wolf ears perked up again.

“The most selfish thing to do would be to push the company to the point of bankruptcy instead of lending a helping hand, then recover as much of the money owed as possible. Force it out of them like, Who cares what happens to you? And if all that was recovered, then they would still have everything from this year’s harvest without even having to touch the money from the mountain sale. Isn’t that fantastic?” Lawrence then deliberately flashed his stereotypically cold merchant’s smile. “If the company didn’t have enough assets left to its name, then not everyone could take back what they lent out. It’s first come, first served. If they take their time, then all that’d be left are the bones that everyone else has already picked over.”

“…That does not sound very tasteful.”

Holo, letting go of Lawrence’s hands and placing her diary under her arm, peered back up at him.

There was something close to fear in her eyes. Just like how humans feared the animals in the forests, the animals of the forests, too, feared humans at times.

“Exactly. And what makes it even more complex is that a weakened sheep can actually get better in the future with appropriate treatment.”

Holo stared blankly at him.

“If it gets better, then it can make wool and milk and bring profits for a very long time, right? Then everyone that’s lending money to the sheep should be able to get all their returns back someday. Basically, if you look at things in the long term, then you can’t really say that simply tearing into the vulnerable creature and plucking the meat off is always the wisest choice.”

Lawrence looked to Holo with a joking smile—You should remember this logic, right?—but Holo only shot him a frown.

“You should only produce silver from your wallet a bit at a time, no? ’Twould all be for naught if you were to lose the seed money for your next venture.”

Holo’s selfishness was well-thought-out selfishness.

“Yes, that’s right. And so Miss Elsa has this injured sheep in front of her and is trying to gather information so she can decide what to do. But that is not the amazing part. What’s most impressive is how she understands that whatever choice she takes will absolutely leave traces of blood somewhere.”

Holo stared at Lawrence, looking at him like a wolf in the wood checking to see how its prey moved.

Then she sighed.

“That fool is not only strict with us but herself as well.”

“No doubt. To be honest, making a decision in a situation like this is the role of the villain. Miss Elsa understands that she’s been saddled with an ugly job, and that it’s the job of an outsider to do that. That’s why she’s not leaving the work to just us two but coming along to the market with us.”

Holo wrinkled her small, shapely nose.

“Sounds like the sort of thing you like.”

“There are people who steel themselves and seek to take on the villain’s role. It means they want to help out.”

“You are too softhearted,” Holo’s stare seemed to say, but she took his hand with a firm grasp.

Though she tended to find things bothersome, Holo herself was softhearted, so Lawrence often felt compelled to stick his nose into trouble and help out. But Lawrence acted to help someone out because he also felt pride as a member of the same flock. It was still a bother, though. And not only that, but Elsa was a woman.

Lawrence figured that must be a close enough reason and looked to the grimacing Holo.

“Come on—cheer up.”

Lawrence lifted his hand, still intertwined with Holo’s, and gently brushed the back of his fingers against her cheek.

Holo narrowed her eyes in slight annoyance.

“You’ll get to see me in action and admire how good I’ll look while doing it.”

Holo stared blankly at what he said next, then gave a wry, exasperated smile.

“Hmm. Think of all the encouragement I shall need to give you when things do not go well and how much consolation you will cry for when you fail.”

She was lightly tapping him with the tip of her tail.

That was the great wisewolf’s compassion.

Lawrence stroked Holo’s cheek with the back of his fingers one more time before leaving the room.

Elsa asked a trustworthy villager to look after the church and joined Lawrence and Holo on the trek to the grand market. Since Elsa could not ride a horse and the mountain roads were wide enough to fit a horse and cart, they decided to travel by cart.

The cart bed was messy with things like the sulfur they had brought from Nyohhira, but it did not seem to pose any trouble with Elsa on her own.

That was what Lawrence had thought, but the atmosphere that hung over the cart took a slight turn for the weird.

To be precise, it was Holo, riding in the cart bed along with Elsa, who was acting strange.

The two were exact opposites, and Holo was acutely conscious of it in one way or another. And so that was why if Elsa sat alone in the back, Holo would grow restless, thinking about what was behind her. But at the same time, the option of Elsa sitting on the driver’s perch alongside Lawrence was out of the question, and it would be even weirder to let Elsa take the reins so that Lawrence and Holo could sit together in the cart bed.

In the end, Holo decided to sit with Elsa in the cart bed, but they were not of course having any sort of pleasant chats. They sat diagonally across from each other, creating the biggest space between them possible, and while Elsa paid Holo absolutely no mind, the hairs on Holo’s tail stood on end.

While she most likely did not hate Elsa, she did consider the cart as her territory. Moreover, Elsa was not someone who could be dismissed as an insignificant opponent, so her presence weighed on Holo’s mind all the more for it.

Though Lawrence tended to forget, Holo was a wolf at heart.

That being said, Holo herself couldn’t exactly control how strong her territorial instinct was, so he refrained from poking fun at her. He knew from his years of experience that she would get genuinely angry.

With that tense air persisting, the cart entered the mountain in short order, passing through a road that was in the midst of transitioning from autumn to winter. Lawrence enjoyed the sound of leaves crunching beneath the wheels as they made their way forward.

When they stopped the cart for lunch along the way, Elsa took the meal as an opportunity to explain the workings of the grand market.

The fair was east from the Vallan Bishopric in the plains on the other side of the mountains in a city called Salonia. The event reportedly took place twice a year, in spring and autumn. The grand market in the spring was as lively as fish leaping out of a lake, while the autumn one was as chaotic as pigs digging for acorns in a forest.

She had heard that from the people of the Vallan Bishopric, and she seemed to like those metaphors quite a bit.

Lawrence, who had made a living as a traveling merchant, knew how fun and difficult the chaos could be, so a vague smile crossed his face. On top of that, the moment Holo went to a fair like that, she would certainly pester him to buy her this and that.

The thought crossed his mind, but he then realized that Holo was nowhere to be seen. She had been oddly quiet during their meal, perhaps because she had become tired of making a fuss about nothing, so maybe she was off moping.

Just as Lawrence was halfway through standing, figuring he should go look for her, Holo came back. When he asked, she told him that she had carved a letter to Tanya in a tree just off the road.

When Elsa mentioned that she had similarly informed the villager she had left in charge of the cathedral about their departure, Holo responded that though the mountain Tanya based herself on was far, she would most certainly notice that they were passing through this mountain. More importantly, she had already experienced the pain of waiting for such a long time, alone, for the alchemists she had parted with. If Tanya learned they had gone over the mountain to somewhere else without further explanation, she would most certainly fall apart.

It was the moment Lawrence thought about how it was odd for her to read so much into something. Holo sat on the dried leaves, about half a foot farther away from Lawrence than she usually did, likely because she was anxious about Elsa, then hunched over and rested her chin on her raised knees. Though they did not sit shoulder to shoulder, she curled her tail around Lawrence’s back.

Holo herself feared that someone who was nothing short of a good friend might leave.

Though she never aged and looked exactly like her daughter, Myuri, there was a difference in standing posture between mother and daughter that was difficult to describe. The reason for that was likely because the emotions Holo kept bottled up on the inside seeped out like this from time to time.

Lawrence was weak to Holo’s childish conduct because he recognized it was partly an act she needed to cover the shards of darkness she kept hidden away. Holo knew that the music would one day stop, which was why she extended her hand to ask him to dance.

Lawrence could not bear to ignore what hid beneath her innocence.

There was the foolish Holo, the one who agonized over where in the cart Elsa should ride, and then there was the wisewolf Holo, the one who, after such a long time, had stored her sadness and hopes into the same box.

There was something worth risking his life over right here.

And so they finished their lunch break and once again set out on the cart when they finally crossed the ridge of the mountains and saw a large spread out in the distance. It was one of the keystones of inland trade, the city of Salonia.

“Mmm. I can almost smell the scent of wheat on the wind.”

Holo’s eyelids drooped, and she flashed one of her fangs. It seemed she had finally grown used to Elsa, perhaps a person she did not get on quite that well with, being in her territory of the cart.

“Endless bread and ale. Is that not the best?”

The wind blew away any caution regarding overeating that Elsa made.

Seeing Holo act like she always did, Lawrence smiled and tightened his grip on the reins.

The town of Salonia was not ringed by towering city walls, but there were dry moats and other earthworks around the perimeter, and they could see the church’s bell tower peeking out from the center of the city. The layout of the city was organic and unplanned; the plazas that dotted the place were likely carried over from the days when this was a simple bartering spot for the nearby farming villages. Now it was piled high with agricultural produce, a lively location for trade.

It seemed that each plaza had a designated product. They could already see well-dressed merchants settling deals and hear the friendly chatter of traders who likely only saw one another once or twice a year.

Perhaps these naturally occurring gatherings were what eventually became the current biannual fair.

“The wheat they are trading here is subpar. There they have oats for horse feed. Hrm, over there is roasted barley. Brewing it would create a delightful drink!”

Holo had regained much of her usual cheer, perhaps because Elsa had alit from the cart as soon as they entered the city. She sniffed and immediately tugged on Lawrence’s sleeve in great excitement like a child.

“Miss Elsa, do you know the way to the inn where all the people of the bishopric are staying?”

In towns like this, once they reached the church at the center of the city, one could go anywhere. He turned the cart in that direction for the time being, but Elsa lightly shook her head at Lawrence’s question.

“I do not. This is my first time in this city as well. We will ask someone.”

Before she was even done speaking, she managed to grab a hold of a passerby, but everyone brushed off her question in a busy flurry.

The fifth man dressed in merchant’s clothes froze at the sight of Elsa, then rushed off.

“…May God guide him,” Elsa said, but she seemed rather unsettled by it.

“You have a scary face. Perhaps he was worried about being lectured,” Holo said with odd glee, so Lawrence poked her in the head.

“It makes sense. Everyone’s busy at this time of year.”

Elsa nodded vaguely as she gently placed a hand to her cheek. Perhaps the remark that her face was scary somewhat bothered her.

Lawrence poked Holo’s head again before catching the attention of a passing artisan’s apprentice from atop the driver’s perch. He sounded all grown up, telling them that he was too busy to respond, but he quickly told them the way once he had a silver coin in his hand.

The apprentice, too, kept glancing over at Elsa.

“Perhaps a female priest is just that unusual.”

Despite his remark, Lawrence knew that their reactions did not come from a place of curiosity at an unusual sight. Many travelers gathered here at the grand market, so there were people from every land and walk of life.

As he wondered what the real reason was, he prioritized meeting up with the villagers staying in the city for the time being.

They reached the inn the artisan’s apprentice told them about and found the tavern on the first floor packed with people. A good handful of people even sat on the ground just outside the inn, drinks in hand. It seemed a little shady at first, except it turned out they were not ruffians but merchants waiting to trade. Some of them immediately held their tongues and hid their drinks behind them when they saw Elsa.

Lawrence understood the reaction, because if a priest saw someone drinking during the day, they would certainly give them a scolding. They ducked their heads down to shrink themselves, and with a small sigh, Elsa simply said, “Be careful not to drink too much,” and continued past them.

But the reaction of those who saw her was noticeably strange. The inside of the tavern also suddenly went still, and a hard silence fell over the place. It seemed like people might even hesitate to cough.

When Holo and Lawrence saw the scene while still seated on the cart outside, they turned to look at each other.

“You were joking when you said her face was scary, right?”

“…You fool.”

Holo had been the one who made the joke earlier but even she seemed bewildered by all this.

They circled around to the back of the inn to drop off the cart before entering the building, only to find the merchants inside whispering quietly to one another. At the very back, Elsa was surrounded by several people.

“Miss Elsa,” Lawrence called, and everyone surrounding her turned to look at him.

There were three men dressed in plain clothes who seemed to be members of the clergy, while the other two were dressed in well-tailored outfits, but the lack of refinement made it clear they had come to the city as village representatives. All of them were a couple of decades older than Lawrence.

“Who are these gentlemen?”

“These are old acquaintances of mine, Mr. Lawrence and Miss Holo.”

“Nice to meet you.”

Each one accepted Lawrence’s extended hand with caution. One of them named himself the village’s head priest. He had forgotten after dealing with familiar guests all the time at the bathhouse, but whenever he traveled somewhere new in the past, this was the norm.

“First, let us guide you to the room.”

They headed up the stairs and ran into two of the younger villagers, perhaps left behind to watch the group’s belongings, though they were currently sitting in the hall outside of the room playing cards. They hurriedly put away their cards and led them through a large suite of rooms.

“The mood is not all that pleasant,” Elsa remarked, and the faces of all the elders clouded over in shame.

“Several of the villagers are on duty at the Laud Company, but it’s hard to say that the situation seems favorable in any way…”

“The entire city is full of life, but it only seems peaceful on the outside. Lady Elsa, did anyone say anything to you when you came into the city dressed like that?”

Lawrence was rather surprised to hear one of the clergymen use an honorific title with Elsa. Elsa often took up jobs she was requested to do, which was how she ended up in the Vallan Bishopric, so perhaps she had made an acquaintance in a high place along the way. The Church had its own unique hierarchy, so even though she was only a temporary priest, perhaps she had earned a fine name for herself as a woman of the cloth.

“Not particularly…But, well…” Elsa signaled to Lawrence with a glance so he took over for her.

“Everyone seemed very surprised to see her in priest’s garb.”

One of the clergymen responded, “I thought as much. Someone got thrown in jail just the other day.”

“What?”

It was not just Elsa who was shocked but Lawrence, too. Even Holo, who had been lazily gazing out the window, was paying attention now.

“If they are so cautious of clerical robes then…was it an inquisitor?”

Holo finally seemed interested when Lawrence asked his question. To a nonhuman, inquisitors were their natural enemies.

“No, the one caught was a merchant. It’s someone we know well, someone who always conducted trade in good faith…”

“There were rumors a little while ago that it might end up like this, but because of that now, if you peel a layer back, you’ll see that all the city folk are on edge, like a wolf who’s been separated from the pack.”

Holo looked like she wanted to know exactly what that particular metaphor felt like in real life, so Lawrence gently touched her back to calm her down before saying, “Which means there are only so many reasons for this person’s arrest.”

He looked to Elsa, and the female priest, who was both knowledgeable in problems of faith and full of worldly wisdom, asked, “Was it debt?”

Not paying back a debt amounted to nothing more than betraying the trust of the person whom one owed.

It could even be considered a sin.

“Despite how lively the city is, everyone is working themselves to the bone because they cannot pay back their debts. Some even say that the reason so many people are carousing in the streets is because they’re watching to make sure the people they lent money to don’t run off.”

Or perhaps there were so many people at the end of their rope that the rumor was spreading as though it were true.

“Even though all the product we brought from the village has already been sold, the Laud Company still will not pay us for it. About five of us—including the bishop, the mayor, and their helpers—are stationed at the company’s building in order to pressure them, but we haven’t gotten them to budge.”

“There are groups from other villages who are apparently in a similar position, so they’re probably arguing over who will get paid first.”

“We have some stores back in the village, but we may be in for a very hungry winter at this rate. How have things turned out for you, Lady Elsa? How much in terms of assets did the church have?”

Elsa had been left in charge of managing the bishopric’s assets.

The woman kept her expression and retrieved the money order from her breast pocket.

“We have managed to sell the cursed mountain off to the Debau Company.”

“Ohhh!”

“What?!”

Everyone grew excited, but Elsa calmed them down by clearing her throat.

“It was Mr. Lawrence and Miss Holo here who solved the secret of the mountain and introduced me to the Debau Company.”

When Elsa said that, their earlier aloofness vanished in an instant. They clasped both Lawrence and Holo’s hands so hard it was painful and pulled them into ecstatic hugs.

“How wonderful! We may buy plenty of goods to last the winter with the money. I wondered how things might end up for a moment there, but I’m certain this news will also give the bishop and the mayor some peace of mind. Let’s call everyone back right away and hit the stores.”

Elsa stood before the men as they voiced relief about how they were glad this matter was settled to one another, and she quickly put the money order away back into her pocket before saying, “It sounds like the Laud Company is in greater trouble than I’d expected.”

“What?”

Elsa looked at the bewildered villagers with eyes that were almost cold.

Holo looked among them, excited that something was about to happen.

“I’ve heard that the Laud Company has worked very hard for the Vallan Bishopric for a long time…Don’t tell me you think everything is perfectly fine as long as we can get by with the money from the sale of the mountain.”

The people of the bishopric were clearly distressed.

“B-but, Lady Elsa, things might turn out badly if you aren’t careful and get needlessly involved in their problems. Are you planning on saving the Laud Company with the money order? The same company that hasn’t paid us yet?”

“If we are able to assist the Laud Company, then it would not be only them that we would be helping.”

“What…do you…?”

Elsa lightly cleared her throat.

“The reason they have not paid you is because they themselves have not yet received payment for the crops that the villagers worked so hard to harvest. By helping them, we will also recover the proceeds for the harvest. Leaving them to their fate would not only be a loss for the bishopric but would also be an insult to the villagers, the lambs of God, who have given their all. Do you really think that as long as we have covered our losses, then all is well? Your way of thinking completely disregards the efforts of those who have worked so hard!”

All the men were taken aback at Elsa’s steadfast moral argument. Lawrence was no exception.

Elsa wanted to help the Laud Company not because they had done anything for her, nor was it because she saw an opportunity to be owed a favor, but because she wanted to protect and honor the bishopric people’s efforts.

However, the first thought that came to Lawrence was the possibility that it might cost more to save the company than whatever the village had earned from the sale of the harvest. In that case, there was ultimately no point, at least financially speaking…The priests seemed to have the same idea. Right as it seemed like they were beginning to suspect Elsa was not looking at reality—

“I looked through all the account books.”

“…?”

Elsa glared at the men and, like an arrow, thrust a finger at them.

“You clearly have no grasp of how to handle money! Waste, unaccounted expenditures, mistakes in calculation—it’s all a mess! What do you even think income and expenditures are?! Perhaps this sloppy accounting was tolerable when the bishopric was thriving, but that does not mean that such behavior is acceptable for servants of God! Is it only at times like these do you think about profits and losses?! What on earth for?!”

They bowed their heads at Elsa’s reprimanding, shrinking in on themselves.

It seemed as though the Vallan Bishopric was not strapped for cash because there was no more rock salt to be found or because the ore mines had dried up. As a holdover from their days of plenty, no one managed expenses properly, and that attitude had been passed along as new hands came to hold the reins. Everyone in charge had been complicit and careless.

But it was not just the village men who reflected as Elsa scolded them; Lawrence did the same.

People from every walk of life put a price on the results of their labor and had to live off that price. While it would be difficult to survive if the gains were not higher than the costs, Elsa tacked on the question of What for?

Lawrence realized he had unconsciously glanced at Holo.

There was little doubt that he loved making money, but there was no question that there was another standard of value. There were times when he would cast aside gains and voluntarily take on losses for this other standard, and it was none other than an act to improve the value of his life.

Elsa was an unparalleled member of the clergy.

Lawrence genuinely thought that.

“That is why I will not allow you to rely on this money order so easily! Take the appropriate measures—ask Mr. Lawrence here to teach you his ways and look into the situation at the Laud Company this instant! This is all to pay back the villagers for their labor, and it is in accordance with God’s will!”

Several full-grown men stood perfectly straight after enduring the scathing lecture of a woman who was both two sizes smaller and two decades younger. Though Elsa had likely come to the Vallan Bishopric as a mediator for a higher-ranking priest, that was not the only reason these men would never be any match for her.

“That is all! May God show you the way!”

Elsa’s lecture finally came to an end, and the thoroughly cowed men timidly approached Lawrence.

The Laud Company was reportedly founded by a family from the south in order to make a name for themselves right when the city of Salonia was starting to develop. The current one in charge was the fourth-generation owner, and in the preceding years, the business had grown to become a midsize company with a fairly good reputation.

Though they fundamentally dealt in every sort of good, their staple was unquestionably wine—typical for companies of a certain size. It was normal for only a very limited number of companies to be issued permits for types of alcohol that would never fall in demand. Because of that, Lawrence could tell that the Laud Company was not in terrible standing within the city.

“They haven’t been dabbling in odd speculations, either, have they?”

The wine the young villagers who had been playing cards outside of the room had prepared for them was likely the kind the Laud Company dealt in. That was the first thing Lawrence asked as he sipped on his slightly sour wine.

“We also suspected it was a failed business deal, too. This is a market full of wheat and farm products…there is no lack of trade that may as well be gambling. At the same time, it’s also full of mutual acquaintances. No one can hide anything.”

Speculating on the futures of next year’s wheat harvest, for example, could either make one rich or rob one of all their money. Lawrence, too, came very close to a dreadful experience in the herring egg trade not too long ago.

“Then did it seem like the company was making money?” he asked, and the priest and villager who were offering the explanations glanced at each other.

“I will not blame you if you are wrong.”

Relieved by Elsa’s reassurance, the villager opened his mouth.

“We didn’t take them at their word…but the owner of the Laud Company insisted that they were doing fine.”

That was entirely possible. Lawrence nodded knowingly, and that was apparently unexpected to someone who was not familiar with the world of trade.

“B-but if they are doing well, then why are they refusing to pay us? How can they be making money and still be in dire straits? It feels like something doesn’t add up.”

Lawrence glanced briefly at Holo, who had settled by the window and was gazing out at the city, enjoying the autumn breeze as she sipped her wine. Then he promptly gave them the same explanation he had given to her, explaining how it was entirely possible for a company making money to still go under. It was a problem that was born from the difference in the calculations in the account books and what actually existed within the cash boxes.

They looked like they had been shown an optical illusion, but what bothered Lawrence was the worrying bonus that usually came with talk of trade.

“There’s something I want to check before I head over to the Laud Company—could you tell me more about the merchant that the Church here threw in jail? The reason for their imprisonment and the general feel of the situation, too, if you can. Basically, I want to know if that’s something the locals here expect of the Church or if it was a big surprise to everyone.”

Holo, whose bangs tickled her forehead while her eyes drooped in content, realized there was nothing in her mug and confirmed it by turning it upside down and shaking it. Only then did she finally turn her attention to the buzz of conversation in the room.

Holo’s ears could hear the lies that people told.

Though they could trust Elsa, it was uncertain if they could trust the rest of the people who hailed from the Vallan Bishopric.

Just as Elsa had been graciously tasked with a touchy decision, there were times when outside merchants were essentially made scapegoats. It was not a good sign if they tried to hide something from Lawrence or even trick him.

That was because if he casually tried to stick his nose into this predicament, it wasn’t out of the question that he could be accused of some crime tomorrow.

Luckily, there was no one who could deceive Holo’s eyes and ears when it came to secretive battles in the forest.

“I-if you’re okay with just hearing what little we know…”

Perhaps pressured by Holo and Lawrence’s stares, the man who apparently worked as the head priest at the Vallan Bishopric’s church explained everything to them.

Moneylending was said to be a great sin that could earn the perpetrators a spot in the deepest parts of hell, but as long as interest rates did not exceed what was appropriate, it wasn’t necessarily a terrible crime. For that reason, the Church did not completely outlaw the borrowing and lending of money.

It would be best to share what one had with those who were in trouble; lending a traveler a blanket for one night, for example, was laudable, and offering thanks when paying back what one owed was also in accordance with the teachings of the faith.

“That is why there should technically be no problem, from a canon law point of view, with giving a moderate loan. That’s why it wasn’t just the city merchants who were surprised, but we were as well…”

“And the ecclesiastical chapter here has always had a reputation of being lenient on trade, which makes it even more so.”

The reason their choice of words was so cautious was likely because they were in the presence of Elsa, who was particular when it came to discussions of faith. No priest wanted to give the impression that they were infatuated with trade and money-making in front of a fellow member of the clergy…

Elsa, however, showed no particular interest and silently waited for him to continue.

“Is there a reason they’re so charitable with traders and merchants? Say…for example, do they get a great deal of donations?”

The head priest and all the others shook their heads in hesitation at Lawrence’s roundabout questioning.

“I cannot say with confidence that they do not, but…I believe their donations fall within what’s expected.”

“Given historical events, I think it’s only natural that the city is so lenient on trade.”

Both Holo and Elsa seemed to have their interests piqued by that statement.

The priests glanced at one another, signaling to each other, and in the end, it was the elder head priest who elaborated.

“For the origin of the Salonia church, we must harken back to when this area was nothing but a featureless field that extended to the horizon in every direction. A small church was built on the spot that hosted an irregular market for surrounding farming villages to barter and for them to sell their harvests to visiting merchants. It is said that a wandering missionary priest settling down here was the starting point of the city.”

If Lawrence’s experiences were correct, then wandering priests who settled down in lively places that belonged to nobody were at best those who had been kicked out and tended to be persuasive men who had little to do with the pious life.

“The priests who came after him worked hard. They even built inns for the merchants who frequented this irregular market. Before long, ever greater numbers of people began to gather, and it started to look more like a town. Eventually, this was declared an official diocese right at the same time the grand market was formally established. As you can see, the history of the Salonia church is one that developed side by side with merchants.”

“In that case, do you think that current events are what led to the sudden arrest of a merchant for the sin of moneylending?”

When Lawrence asked, Holo shrank back slightly.

The world was currently roiling over the question of what shape faith should take. It was by and large the Church’s own doing, since they had long simply done as they pleased, but the ones who stood at the center stirring the pot were none other than their inexperienced daughter, Myuri, and Col, so Lawrence and his wife could not exactly pretend like they were totally uninvolved. They were both proud and terrified that the children they had raised themselves had gone out into the world and were making such big waves. And like anyone would know if they moved a big crate that had been sitting untouched in storage for a long time, even the slightest shift would kick up a lot of dust.

Col and Myuri’s adventure was bringing a wave of change, and they knew that was not always a good thing. When he got right down to it, this commotion was the main reason Lawrence had traveled all the way to the Vallan Bishopric where they ran into Elsa.

That being said, there was no way for the gravely nodding head priest to know that the flagbearer of the Church’s reformations sweeping the world was essentially Lawrence’s son.

“That is exactly why…I cannot say it’s a bother for the Twilight Cardinal, though…”

As a clergyman who worked in a church, he heaved a heavy sigh. Holo, who seemed ill-mannered yet was surprisingly conscious of how others saw her, looked away like a cat when she saw his troubled face.

“Our bishopric received a notice from the archdiocese as well: Adjust your assets to a reasonable level so that they are in accordance with God’s will. That is why we received Lady Elsa’s help. And…actually, the reason all of us including the bishop are here is related to this problem. We have been hearing disquieting rumors for a while now.”

“Disquieting rumors?” Lawrence asked in return, and Elsa spoke up.

“That churches and cathedrals in market towns with thriving trade are under special orders to eliminate certain transactions that can act as hotbeds for dishonest business. You must be aware of this.”

He had told Elsa about the herring egg trade in Atiph.

Lawrence hummed. “So that means the futures market for wheat and farm produce might be regarded as gambling and subsequently banned.”

“That’s right. We buy all sorts of goods in order to get us through the winter, but we never buy what we see in the shopwindows. It’s normal practice to reserve wheat, oil, and meat for the future. That is suspected as a form of gambling every now and then.”

Many forms of trade were born out of necessity. Lawrence did not feel the need to comment on it and simply nodded.

“On the slim chance that all futures trading was banned, there would be chaos. And so when we came here to make sure that wouldn’t happen, another problem cropped up.”

“Yes, we could see that there would be a big commotion if so much trade was stopped. The bishop here in this town understands that as well. However, not doing anything at all invites suspicion of vices and corruption.”

“And so the bishop of Salonia came up with a plan…Surprisingly, he thought it would be for the best to throw a merchant in jail, all for the sake of protecting trade.”

That was an unexpected reason.

“That was the best option? To put a merchant behind bars?”

“Yes. Everyone in this city right now is riddled with various debts, so people are finding it harder and harder to conduct business. Even though there is so much trade occurring—it’s all quite strange. Eventually, the bishop decided he had had enough and used the authority of God to shock the market back into normalcy.”

Everyone was suffering from debts piling up because no one was paying what they owed, which simply exacerbated the situation. By warning them that not paying back debts had consequences, payments would in theory begin flowing again.

Though Lawrence could somewhat understand the logic, he couldn’t help the bitter expression that crept onto his face.

“Did it not have the exact opposite effect, though?”

The head priest and the villagers glanced at one another again, then hung their heads as though it had been their own mistake.

“That’s exactly right. Even we’re terrified that we might also be thrown in jail at this rate, and while the amount of coins circulating is scarcer than ever, the collection of debts has become even more relentless. We’ve heard that the biggest company owners are locking horns in heated talks and that has somehow kept transactions going in the meanwhile. But we’ve also heard that they’re refusing any resolution that involves handing over even a single silver coin to other companies.”

What would happen if someone came along and tugged on both ends of a tangled thread without thinking?

Any remaining breathing room would vanish, and the thread would become even more tightly knotted.

“Why have things come to this?” the head priest asked in a fit of despair. “The city is practically overflowing with trade.”

The nearby open window offered them a good look at the bustling city.

The crossroads were almost unimaginably busy, and the inns and taverns were brimming with customers.

“There are times when we even wondered if there’s a demon hiding in this city,” the man beside the head priest muttered weakly. Elsa raised an eyebrow, and the head priest was startled when he heard him say that.

The lively city of Salonia, falling into chaos for apparently no reason because a demon had slipped into the throngs of the markets and was secretly causing problems.

It was a relatively common suspicion, but Elsa’s eyes were surprisingly stern.

“Were you being serious when you said that?” Elsa asked, and the head priest frantically spoke up.

“Everyone, including the bishop of Salonia, lives in proper faith. That is an entirely groundless rumor…Any talk of a demon is certainly not…”

These flustered reactions were likely due to fear that Elsa, who seemed to have ties to influential members of the Church, might call in an inquisitor. If that happened, it was plain to see that the Vallan Bishopric, which bordered the city and actively traded with it, would get caught up in the ensuing maelstrom. Additionally, they were currently in the city itself, so things would become very complicated indeed.

Their worries were unfounded, though, since it seemed that Elsa’s question had less to do with faith and more to do with Holo. Perhaps a nonhuman like Holo had slipped into town and was making use of some mysterious power.

Elsa turned to Holo, whose lips upturned slightly as though saying “You blithering fool,” and looked away in a huff.

Watching their exchange, Lawrence slowly took a deep breath.

He had a feeling this was all the information they were going to get here and now, and he had a general idea of the current situation.

It was obvious what an ex–traveling merchant should do.

“Well then, why don’t we go searching for this demon?”

After all, business couldn’t be done while standing still.

Naturally, everyone’s attention turned to Lawrence.

Clerical robes garnered far too much attention, so Elsa changed into everyday wear before their group set off for the Laud Company. They saw all sorts of farm produce being bought and sold on the street corners, food stalls packed close together, and a dense crowd gathering before a theater troupe.