CHAPTER FOUR

To journey back through the snow would require a certain amount of preparation.

This was why merchants so frequently boarded in inns for weeks and weeks during the winter. Even the most familiar, well-trod road became a foreign country when it snowed. Worse, a treacherous spot looked no different from a harmless field when covered in snow.

Winter travel required many things—a guide, a stout horse unfazed by deep snow, knowledge of lodges and cabins in which to pass the night. Travel took more time so food and water rations had to be calculated appropriately.

But fortunately, as long as there was demand, there would be supply. And it was no overstatement to say that the merchant quarter of the great Brondel Abbey was filled with travelers as far as the eye could see. Lawrence went to Piasky to ask after the services of the packhorse driver who had guided them on their way in.

Piasky was busy with documents at the alliance inn and was momentarily surprised at Lawrence’s announcement that they would be leaving. But as winter travel required quicker resolve than summer journeys, and as Lawrence had compensated him rather generously for his services, Piasky readily agreed to help.

When a search for knowledge gave no results, a quick retreat was called for. If one had time to idly waste, it was better spent hurrying on to the next goal. While merchants greeted one another with happy smiles and handshakes, they parted just as happily.

It was a rather lonely way of getting by, but it had its advantages.

“This should put everything in order, then.”

“I very much appreciate it.”

“No, not at all. I’ve hardly been much help.”

They exchanged merchants’ pleasantries that were meaningless, though it would not feel right to skip them.

However, the handshake they shared next was anything but meaningless.

Just as a person’s qualities could be seen in their bearing, their history came through in their handshake.

The moment of that handshake was the one that decided just how long a person’s face would remain in memory.

Lawrence took Piasky’s hand firmly and fixed his face solidly in his mind. He hoped Piasky would remember him equally well.

“I think we’ll be able to leave tomorrow. Although…”

“Although?”

“A regular delivery from the capital in the west just arrived, and evidently the weather there is terrible. A messenger expected to arrive today still hasn’t been seen. Doubtless that same weather will arrive here soon.”

A blizzard could turn the entire world literally pure white. The most capable horseman in the world would do them no good at all.

“I’ve naturally no inclination to persevere in the face of a blizzard. There are three things you don’t defy: the Church, an infant, and the weather.”

Piasky smiled and nodded. “With luck, it will veer north. And since the shepherds should return soon, I’ll ask their advice. They’ll have the best knowledge of conditions outside…Ah, Mr. Lawrence, aren’t you staying in the same lodging as they are?”

“We are. It’s the best place to gather such information.” Lawrence gave a quick bow after this joke and then put the alliance inn behind him.

Outside, the approaching twilight lent a melancholy tone to the air, and the sky was indeed cloudy, with a bit of wind.

The merchants in the street had a quickness to their strides, their heads filled for once with thoughts of a warm dinner rather than money. For his part, Lawrence had not only his promise to uphold to prepare dinner for Huskins, but there was also Holo to think about.

“A blizzard?”

Having tossed the last of the ingredients into the pot, Lawrence handed the ladle to Col to mind and went to sit on the bed by Holo, who was grooming her tail.

“The weather may turn bad. If it does, our departure may be delayed. Two days, even three…”

“Mm…now that you mention it, you may be right. My nose has gone numb from smelling naught but sheep.” Holo sniffed twice, then sneezed. Once accustomed to travel, there were even some humans who could predict the weather with their nose. “Ah, well, I suppose it’s too late to complain about a few days’ delay, isn’t it?” She grinned mischievously and chewed the tip of her tail.

Lawrence held up both hands in his usual display of surrender.

Holo chuckled, giving her tail a final stroke before falling back on the bed. “So, then, what of dinner?”

“It’s not finished boiling yet. And we’re waiting for Huskins to return.”

Holo hid her fluffy tail beneath her robes quite adroitly, but she had not pulled her hood over her head yet. Lawrence followed her as she went, and when she rather rudely stopped to snatch a piece of jerky from the pot, he covered her ears with the hood.

“Sho, whensh he coming bhack?”

“Soon I imagine. There’s no moon tonight, and there’s the cold.”

Col was wrapped in a blanket as he sat by the hearth and tended the pot, and whenever anyone spoke in the room, their breath turned to white vapor. Outside the windows, the wind was growing stronger and stronger, and the night’s weather looked to be turning bad.

“Mmph…well, I’m hungry.”

“And he’s out there raising that mutton. You should pay him some respect.”

“Aye, but when have you paid me any respect?”

It was hard for Lawrence not to immediately reply with, “And just when did you raise me, hmm?” It was all he could do to express his frustration with a reserved “Honestly.”

Holo grinned at Col, and the softhearted Col only smiled a chagrined smile.

Just then, Holo’s gaze flicked to the door, and Lawrence knew their company had arrived. And from her cautious expression, he knew, too, that it wasn’t Huskins.

Perhaps it was Piasky? Lawrence wondered, just as there was a knock on the door. Col, who was used to doing such menial tasks, opened the door, and there stood a shepherd with his cane.

“Ooh, what a lovely smell. Huskins is putting up good travelers, indeed.” He seemed to recognize Col, patting the boy’s head before clearing his throat. “Apologies. It seems Huskins will be spending the night in the sheep barn. The snow’s already begun to come down, you see. My two companions and I barely made it back with our lives.”

“I see…We’re sorry to make you go out of your way.”

“Not at all. There’s nothing so hard as waiting for a comrade to return, not knowing when or whether they’ll come.”

Coming from a shepherd of these snowy lands, this statement carried a special weight. When both darkness and snow fell from the sky, all people could do was huddle around their fires, wondering if their comrades were alive or dead.

“All the more so when there’s a tasty dinner waiting!” said the shepherd with a huge smile and then raised his hand. “That’s all!” he finished, then walked off.

A merchant would have asked for a cup of soup before leaving, but shepherds were not such greedy creatures. All they relied upon out on the wide-open plains was their staffs and their sheepdogs.

Perhaps their great pride came from that independent spirit—and in any case, that pride of theirs reminded Lawrence very much of a certain wolf. Though he was quite sure that if he said so to Holo, he would truly bring her anger down upon him.

“So that means we’ll have to wait until at least the day after tomorrow. Let us hope the harbor doesn’t freeze solid,” said Lawrence, closing the door and turning around.

Holo stole the ladle from Col. “Aye. Let us hope our soup stays unfrozen as well, eh?” She appeared quite pleased, given that she seemed not to think particularly fondly of Huskins. Of course, no small part of that was doubtless due to the share of meat Huskins would have been spared.

“It’s not even done cooking yet,” said Lawrence as he added a not inexpensive piece of firewood into the hearth.

That night…

Col had quickly fallen asleep, followed not long after by Holo. Outside the window, the wind howled. Their room’s window was not the only one clattering loudly, mixing with the occasional sheepdog’s bark—perhaps they, too, were being affected by the unpleasant atmosphere.

The night before a blizzard was ever thus.

This time there was a difference, though. Usually Lawrence would be unable to stay warm no matter how many blankets he wrapped around himself, but this time he was almost too warm.

Holo’s tail was there, and nothing was better than another warm body to keep the cold at bay. On that count, Holo’s was always a little warmer, like a child’s, and with wine in her, she was warmer still.

Outside the blankets it was almost painfully cold, but within them, it was as warm as spring.

Yet there was a reason he could not sleep.

The current episode was showing him quite clearly that he could not hope to solve all of Holo’s problems. And what haunted him still more than that was the question of what to do next.

If Holo bared her fangs and settled the question of the wolf bones, this chapter would come to an end no matter what the outcome.

If they existed, the story would be over, but it might end even if they didn’t. Lawrence couldn’t imagine any monk capable of lying while his head was between the jaws of Holo in her true form.

If the answer was that the abbey had not purchased the bones or had already resold them, would they continue to pursue them?

And what if the bones had gone south? Traveling there was possible, but in addition to the expense, it would mean throwing away all the business he’d built up over the course of his trade route. And if it was too long, his customers would be unable to receive goods they were counting on, and the trust he had worked so hard to foster would vanish.

There was a limit to the detours Lawrence could afford.

Though he might wish to consider his dramatic, adventure-filled travels with Holo, just as the abbey was unable to escape its financial woes, so too did Lawrence have to make a living.

The simple, obvious truth was that he would only accompany her as long as he was able to.

Holo certainly understood that, but as soon as Lawrence began to consider simply making straight for Yoitsu, peaceful sleep became nothing more than a memory.

If they headed for Yoitsu, how much longer would he be able to stay with Holo?

And the biggest problem was what would happen once they arrived there. The problems they’d kept putting off were expanding now, like yeast in bread.

What did Holo think? At the very least he now knew she regarded him with some fondness.

But she was not a child, and the world would not simply accommodate their preferences. They would have to be prepared. Holo was the Wisewolf of Yoitsu, and he was a simple traveling merchant. A relationship that crossed social classes was cause for worry enough, and that was when it was between two humans.

So how prepared would they need to be?

Holo lay next to him; he smoothed her chestnut-brown hair and placed his hand on her head. When she fell asleep after drinking, she wouldn’t wake even if he pinched her cheeks. In carrying her drunken body to the bed, he’d earned the small reward of stroking her head.

“…”

Holo’s hair slipped through the spaces between his fingers like silk.

She is so dear to me, he thought.

He wanted to stay with her as long as he was able, even if it was absurd, even if it made him miserable. No matter how foolish it seemed.

But as soon as the thought occurred to him, he heard a quiet answer. Are you truly prepared to make such a decision?

Lawrence sighed and stopped his hand.

Though he might wish to borrow the wisdom of a wisewolf, he knew it was a problem he had to solve on his own.

Resisting the urge to curse, he looked again at Holo beside him. He was quite sure he had never made so pathetic an expression in his entire life.

“—!”

He froze, but not because Holo’s deep, sleeping breaths had stopped, nor because he had noticed her trying to hide her laughter.

He thought he heard something—the sound of something being dragged perhaps.

“…?”

Holo seemed to still be sleeping as she had been, the sound of her blissfully ignorant breathing barely audible from where her face was buried in the blanket.

Lawrence listened carefully but heard only the sound of the shutters rattling and the wind howling.

Perhaps some snow had slid off the roof, he mused, relaxing—but just as he did so, he heard the sound again. This time it was definitely not his imagination.

He raised his head, listened intently, and heard it again.

There was no mistaking it.

Lawrence slowly inhaled, letting the frigid air flow into his lungs. He then quickly emerged from within the blankets, placed his feet on the creaky floorboard, and stood there in the stabbing cold.

He unsheathed his knife, opening and closing his right hand around its handle. Thieves were surprisingly common in places like this. They evidently exploited the lowered guard that came with seeing only familiar faces.

Continuing to the room with the hearth and opening the door there, Lawrence could now clearly hear the dragging sound.

The sound of a staff.

If it was a thief, he was giving a poor accounting of himself, and Lawrence was not so foolish as to mistake the sound for stealthy footfalls. But who could it be at such an hour?

“Nn…mph…”

Holo rolled over in bed, seeming to notice that Lawrence was no longer there.

She sat up, rubbed her eyes, and looked in Lawrence’s direction questioningly.

But her sleepy-girl act ended there, and she soon took notice of the footsteps, her eyes becoming wolf’s eyes.

With movements so quick it was hard to imagine she was still drunk, she threw off the blankets, but could not win against the cold and shivered once.

The footsteps were very close now.

Shfff…tup…tokk.

Holo looked back and forth between Lawrence and the doorway. She seemed to want to ask who was there, but Lawrence did not know himself.

The sound stopped at the door. Slowly the handle was turned, and the door opened…

“…Hu—” Lawrence began, but didn’t have time to finish before rushing toward the figure, who started to collapse.

And then Lawrence was speechless. In front of him was a snow-covered, barely alive form that looked very much like Huskins but was hardly human.

Lawrence found himself utterly unable to form words.

“…”

Icicles dangled from the figure’s eyebrows, and it was impossible to tell whether the beard that rimmed his mouth was ice or hair. The hand that gripped the staff was caked in encrusted snow, and it was impossible to tell where the hand ended and the staff began.

His breathing was quiet. Eerily quiet—and beneath the snow and ice, only his eyes moved, glancing this way and that.

No one spoke.

Their demonic visitor’s back was oddly shaped—from his head sprouted a curled ram’s horns and his knees were jointed backwards, like a sheep’s.

“…Oh, God,” murmured Lawrence, mostly unconsciously.

That instant, the ice covering the demon’s face split with a small krak.

By the time he realized the demon was smiling, Holo was right by his side.

“…A wolf, eh…” As he spoke, the icicles dangling from his beard clattered against one another.

The voice belonged to Huskins.

“Had you not the time to disguise yourself?”

“…” Huskins smiled wordlessly and slowly wiped his face with the hand that did not hold his staff.

He looked as though he had endured something that would have long since killed a normal man.

“You’re here to mock me, then?” Holo’s voice was colder than the air in the room.

The half-man, half-beast demon called Huskins narrowed his eyes, as though he were looking into a bright light, staggering as he tried to stand. Lawrence reflexively tried to support his shoulder.

He was a demon. That was it—he was a demon.

But Lawrence had a reason for lending him a shoulder to lean on—Holo had not tried to hide her ears and tail.

“…Is it not natural…for a sheep to hide itself before a wolf?”

The sound of cracking ice accompanied his movements.

Lawrence helped Huskins over to the hearth, where he sat.

Shortly thereafter came a small cry—the sound of Col’s gasp upon awakening.

“The best place to hide a tree is in the forest, eh? I never noticed.”

“…I am not like you.” Huskins fixed Holo in one eye.

Lawrence could tell from Holo’s ears and tail that Huskins’s words had disturbed her.

But she still had the ability to admit reality. She nodded. “And?” she said grudgingly.

Huskins was a being similar to Holo. In and of itself that did not bother Lawrence. His travels thus far had taught him that such creatures did hide in human civilization—in ominous forests next to towns, in segregated districts where townspeople feared to tread, or in fields of wheat, long after the villagers had lost faith in them.

So if anything, Lawrence was calmer than Holo as they waited for Huskins to speak.

“I have…a favor to ask.”

“A favor?”

The melting ice refroze in the chilly room.

Huskins nodded again emphatically, sighing as he spit out the words. “It’s a calamity…one far beyond my power to deal with.”

“So you wish to borrow mine?”

At Holo’s question, Huskins seemed to nod—but when Lawrence realized Huskins was not nodding, but rather shaking with mirth, Huskins put a trembling hand to his breast and produced a letter.

“Your power is your fangs and claws…but the age when such things ruled has passed. I give you this…” He directed his gaze to Lawrence.

“To me?”

“Yes…to the man who travels with the wolf. I let you stay here because…I wished to observe you. But I believe it was the will of the gods.”

“Hah, the gods, you say?” Holo bared her fangs and laughed derisively, but her intimidating, contemptuous expression elicited only a cold smile from Huskins.

“Just as you cling to this strange, gentle human…so, too, do I cling to the gods. That is all.”

“I-I do not—I hardly—!” Holo objected mightily, at a rare loss for words.

The difference between Huskins and Holo was like that of an old man and a child, and it was not simply due to the disparity in their appearances. For example, Huskins regarded the sputtering Holo but gave no triumphant, boastful smile. Quite the contrary, his expressionless face seemed to be somehow tender and kindly.

“You’re a merchant, are you not? Take this.”

“What is it…?”

“I found a strayed shepherd in the snow. Such things often happen…my sheepdog found him. He looked to still be praying, though the life had already left him.”

It was a single sealed letter. Written on sheepskin parchment with hair still on it, it was sealed with a red wax seal.

If the man had died out in the snow, he must have been a messenger from some other town bound for this one and had gotten lost on the way.

Unless travelers hurried, they would be caught by the snow and wind and night, but hurrying rapidly exhausted their reserves of strength. It was such a common occurrence that there were even thieves who specialized in finding their corpses once the snow melted and taking their belongings.

“In the end, I am a mere sheep. You understand, do you not, young wolf?” Huskins directed his words to Holo. Holo clutched her chest, as though a secret she held had been revealed.

“In the face of this letter, our strength means nothing,” finished Huskins, giving a heavy sigh. He closed his eyes.

The firewood had now fully caught the hearth’s flames and burned very brightly. The ice on Huskins’s body was finally beginning to melt, and Col had recovered enough to busy himself tending to Huskins, who seemed to find the attention pleasant.

At some point his body had reverted to human form, and it seemed like his earlier monstrous form was something out of a dream.

But as she continued to stand and look down on Huskins, Holo’s ears remained uncovered, her tail occasionally visible.

Lawrence looked at the contents of the letter Huskins had given him. And then he understood what Huskins had meant.

“Mr. Huskins. What do you need my help for?”

“The abbey…” Huskins paused for a moment, then closed his eyes and smiled thinly. “…I want you to protect it.”

“Er, I’m sorry, but—why?”

Huskins opened one gray eye and regarded Lawrence with it.

His gaze was steady and dignified, the gaze of a wild sheep that had roamed step-by-step across the vast plains.

It was different than Holo’s.

If Holo’s gaze were a sharp dagger, Huskins’s was a great hammer.

“It’s no surprise you’d wonder. Why would I, of anyone, bow down before God? You see, I too have relied on humans to live. Just like the young wolf.”

Instantly Holo seemed ready to refute him, but she was stopped by a glance from Huskins.

He was treating her like a child.

“I do not mean to anger you. I have taken human form and live a human life. It is no surprise I sought human strength.”

“Hmph. So, what have you done with this strength you’ve borrowed from the humans?”

“A home.”

“Eh?” Holo replied, her eyes widening.

Huskins continued, his voice and manner still quiet and clear. “Made a home. On this land. A home of our own.”

The firewood crackled.

Holo’s eyes were like full moons.

“Nothing escapes the grasp of humans. Not the mountains, the forests, or the plains. So in order to create a place that would endure unchanging for centuries, we had no choice but to use their power. At first I was unsure whether it could succeed…but it did. A vast, quiet homeland was ours. And no matter who comes or when, they always say the same thing.”

“…This place hasn’t changed.”

Huskins smiled like a kind grandfather and took a deep breath. “It’s our greatest desire. We were driven from our home long ago and scattered. Some to desolate wilderness, others hiding among humans in their towns. And some wandered endlessly…This is a place where we can all meet again. A place to which all may return, no matter how far afield they live. This place.”

“That which scattered you…could it have been, was it the Moon-Hunting…?”

“Ha-ha…hah. So you know that much, do you? That will make things simpler to explain. Yes, it was indeed the Moon-Hunting Bear that took our home from us. Irawa Weir Muheddhunde in the old tongue.”

They had seen many stories of the bear that had been collected by a certain priest back in a tiny, meager town that worshipped a snake god.

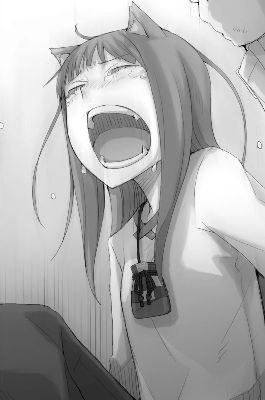

Holo took a deep breath, like a child with a strange way of crying.

“When the calamity came, we were powerless, and there was nothing we could do. And now times have changed, and to protect this place, we need a new kind of power. The devices of humans are too fine for my hooves.”

When seeking a favor, it was very difficult to maintain an equal footing, neither abasing oneself nor being too demanding—nor too prideful.

But Huskins accepted the world as it was, and within it, did what he was able. And there was no doubt he had done so for centuries. So it had to be possible.

“We’ve had many troubles thus far. But this time, finally, they may be more than we can handle.”

Lawrence looked at the letter, then back to Huskins. “…This is a royal notice of taxation, isn’t it?”

“It was easier when the lords were still warring. The reason of our own era was enough to gain some small measure of stability then. But the long wars devastated the land. If the abbey were to fall, all would be lost. So I secretly aided Winfiel the First in unifying the nation. And that is where I erred.”

They were stronger than humans, and wiser, and had ruled the land before humans swept across it. The turn of ages was a common matter to them surely.

“But children never remember the debt they owe their parents, to say nothing of grandchildren. I can no longer take the public stage. All I can do is occasionally show myself to add a bit of legitimacy to their rule.”

“The legend…of the golden sheep.”

“Quite so. Of course, a few of those moments were due to my own carelessness when greeting a friend I’d not seen in ages.”

Jokes were all the more amusing when told in an inappropriate place and time. But once the ripple of ensuing laughter was over, it left behind a now obvious sense of nervousness.

“I’ve no head for counting coins, but even I can tell the abbey is on the verge of ruin. With each round of taxation, the pay we’re due falls more behind. Our friends have told us the abbey may not endure another round.”

“But this is…”

“I no longer know what to do. If I could stamp it with my hooves or grind it with my teeth, I would do so…but you’re a merchant, are you not? When humans drove our kind from the forests and mountains, there were always merchants in the shadows. To see one such merchant laughing with a wolf…” He heaved a long sigh. “You’re the only one on whom we can rely.”

“But—”

“I beg you.”

Lawrence had traveled alone for seven years. Many times had he delivered a final letter from a fallen comrade to a family. Confronted with a scene he did not wish to remember, his words failed him.

If it were a simple letter, he would accept it. But what Lawrence held in his hands was a royal notice of taxation.

“No.” As Lawrence continued to struggle for words, it was Holo who spoke up. “No. We cannot take such a risk.”

“Holo…”

“If you cannot do it, you must refuse. And you yourself said that getting involved in this business was dangerous. We shall leave tomorrow. If not tomorrow, then the day after. We are travelers. This has naught to do with us.”

After this barrage of words, Holo’s quick, short breaths were all that remained.

Had she seemed merely serious, Lawrence would have been angry, but Lawrence instead stood there blankly, leaving Col to tend to Huskins. When Holo came to her senses and looked at Lawrence, she shrank away.

Her expression was hard to describe.

Her tense lips made her seem angry, but she was trembling as though deeply sad. Her shoulders sagged, her fists clenched, and her face was very pale.

Lawrence could barely stand to look at her.

It was her jealousy that made her this way.

“Su-surely ’tis so, is it not? You said as much yourself. You said that it was dangerous. That is why I said we should leave. And yet—and yet you’re considering his request…!”

“Holo,” said Lawrence, taking her hand. She pulled away once, then again, then a third time, and then was docile.

Tears fell from her face.

She knew perfectly well that what she was saying was childish. She’d been able to endure listening to Piasky because his work was meant for humans. But Huskins was another matter entirely.

Worse, Huskins had lost his homeland to the Moon-Hunting Bear, which had also destroyed Yoitsu.

Huskins spoke. “Young wolf, was your home destroyed by him as well?”

Holo looked at Huskins with eyes that swirled with jealousy, envy, and agitation.

“We did not gain a new homeland easily. We took human form, became shepherds, and lived our lives quietly and unobtrusively. And we were prepared to do whatever it took to defend this land.”

“I could—!” Holo’s hoarse voice was somehow small, even as she cried out. “If it were to bring back my homeland…my Yoitsu…I, too, could…”

“I cannot but think you’ve never fought the bear, have you? Are you prepared to risk your life battling it?”

Holo’s face filled with rage. She surely thought Huskins was mocking her. Yet Huskins quietly and steadily gazed into her furious, red-tinged amber eyes.

“When he came to my homelands, I ran. I ran, you see, because there were many who I knew needed my protection. I led them away, and we escaped. I can remember the moment even now. There was a great full moon in the sky that night. I could see the ridge of the mountains across the vast plains, and above it shone the bright, bright moon. And we fled the plains—those fertile plains whose grasses we’d long grazed upon.”

Huskins body was visibly weakened. Like Holo, assuming human form surely subjected him to human limitations.

And yet he continued, the words falling from him as though the hearth’s flames were melting his frozen memories.

“I looked back in the direction of my home, and I saw it. The shadow of a vast bear so huge it looked as though it could sit on the ridge of the mountains. It was beautiful—even now, I think so. It roared, it raised a paw up as though to hunt the moon, and that moment still…”

The tale was from the distant past, when the hand of humans had yet to reach out—an era when the world still belonged to darkness and spirits.

“Even now, I think upon it fondly. It was the last great ruler of our world. It was a time when power and might ruled all. All my anger has left me. All that remains now is my nostalgia…”

Holo had missed the fight for her homeland and had only learned of its destruction centuries later—so forcing a childish smile was probably all she could manage. “F-for you, who ran like a coward, to speak of preparation…it is to laugh.”

It was childish stubbornness, and the wily, old Huskins countered it with ease.

“To live among the humans in their world, I started eating meat. It’s been centuries now.”

“…!” Holo’s eyes immediately went to the drying meat that hung from leather thongs. What kind of meat was it? And what kind of meat had been in the stew they had eaten with Huskins? After a few gasping breaths, Holo vomited.

Lawrence did not know if she had imagined herself doing the same thing Huskins had done or if she was simply prone to tears.

Huskins had been willing to eat the meat of sheep in order to pose as a shepherd.

Could Holo do the same thing?

“To keep this, my homeland, we have given up much. We have crossed lines that should never have been crossed. And if it is lost, we may never find another land where we may live in peace.”

He did not say these words to attack Holo. He was simply trying to be as clear as he could in defending his reasons for asking Lawrence’s help.

But still, Holo was envious of how Huskins had created a new homeland here.

She herself knew full well how foolish it was to envy someone who had struggled to re-create something they had lost. And not only that—she wanted to turn her back on them, to abandon someone who’d created a new homeland.

If she was interpreting Huskins’s words as an attack, it was because of her own guilt. Holo was caught between reason and emotion and finally chose to run.

She burst out crying like a child, and Lawrence caught her as she collapsed on the spot.

Huskins waited for Lawrence to put his arm around Holo before slowly speaking.

“…I’m well aware that your young wolf there has suffered greatly in this world. And by some unfathomable luck, she’s come to travel with a kindhearted human. I understand that she doesn’t wish to part with that. I understand that she wishes to protect it. But…,” said Huskins, slowly closing his eyes. “I, too, do not wish to part with this land. Our hard-won refuge…”

His words trailed off, and Col hastily put his hand to Huskins’s broad chest. Seeing Col’s obvious relief, it was clear that Huskins had merely exhausted himself.

Lawrence listened to the crackling firewood and the sobbing Holo as he looked over the notice of taxation Huskins had given him. The order of taxation written there would be extremely difficult to refuse.

The best way to avoid paying taxes was to protest that one had no assets with which to pay, but the king had chosen a solution that would render such protests meaningless.

The king’s resolve was clear, and there would be no wriggling out of it. If there was any hesitation, it would be met with military force. That might even have been the real goal.

A single pack could not be led by two heads—Holo had told him this, but it held true for a nation, as well. The abbey, with its great influence and huge tracts of land, was certainly a headache for the king.

Ruin if they paid the tax. Ruin if they didn’t.

From this impossible predicament, the abbey needed salvation—by Lawrence, a mere traveling merchant.

“It’s—it’s impossible,” Lawrence murmured without thinking.

Picking up on his words, it was Col who looked up. “Is it impossible?”

Col had ventured out into the world to protect his own town. His eyes were deeply serious, almost accusing Lawrence.

“…Once during my travels, there was an accident. The road was muddy from rain the previous day.”

At the sudden change of topic, Col’s face showed a rare flash of anger. Lawrence was a merchant, and merchants often used clever misdirection—and Col knew it.

“The lead cart sank into the mire. We hurried to it and discovered that the merchant driving the cart was fortunate enough to be alive. He was flat on his back and looked quite embarrassed. He seemed to be injured, but we thought he’d survive. We thought so, and so did he…”

Lawrence continued to stroke the sobbing Holo’s back as he spoke to Col.

“But his belly had been opened. A tree branch had gotten him maybe. He didn’t even realize it until he saw our expressions. He smiled stiffly and asked us to save him. But we weren’t gods. All we could do was stay with him until the end.”

Sometimes there was nothing to be done. That was the way of the world. There was no divine mercy, no heavenly fortune, and time could not be turned back.

Lawrence sighed and continued.

“It’s not that I wasn’t sympathetic. But I also know the God who’s supposed to deliver us seems to be so often absent. All I can do is be glad it wasn’t me.”

“That’s not—!”

“That’s all there was to do. And after I saw my unlucky friend off, I stood up and continued my journey, after taking as much from his cart as I could.” One corner of Lawrence’s mouth curled up. “It was a nice profit,” he added.

Col’s face distorted, and he seemed about to scream at Lawrence, but in the end he did not. He looked down and resumed his work of drying Huskins’s wet hair and beard.

When faced with unavoidably trying circumstances, immersion in work could bring salvation. Lawrence wondered how long ago it was he had learned that. He thought about it as he picked Holo up. She was quiet in his arms as he took her to the next room, though whether she had cried herself to the point of exhaustion or simply passed out from stress was not clear.

The snowstorm raged outside, but because the snow had long since accumulated in the cracks in the walls and windows, it was not terribly cold.

Holo’s breathing was quick and shallow, as though she were suffering from a fever. She was probably having a nightmare or else her guilty conscience was continuing to assail her.

He laid Holo on the bed and turned to go attend to Huskins, but she tugged on his sleeve. Her eyes opened just slightly. Those eyes had abandoned shame and pride and simply implored him to stay by her side.

It was not clear how conscious she was, but Lawrence stroked her head with his other hand, and Holo closed her eyes as though reassured. Slowly, one finger at a time, her hand let go of his sleeve.

In the next room, illuminated by the redly burning hearth fire, Col struggled to change Huskins’s outer layer of clothing. In addition to the difference in size between the two of them, Col was not terribly strong to begin with.

Lawrence silently set about assisting, and while Col did not thank him, he also did not turn the help away.

“There’s no danger in considering it at least.”

Col’s face showed surprise, and he said nothing in response. He looked up and paused.

“Pull there, please.”

“Ah, y-yes!”

“There is no danger in considering the possibility. After all, at the moment, we’re probably the only people who know about the contents of this letter.”

Huskins’s things had been arranged in a corner of the room, and from among them, they found clothes for him and removed his soaking-wet shoes.

“Given how important the message is, I can’t imagine they’d send just one copy. Once the blizzard is over, I’m sure someone will arrive bearing the news. Which means we have a few options.”

Whether or not to tell anyone else about the letter. And if so, whom.

“Do—do you think anything can be done?”

“That’s hard to say. But we can make some predictions. The abbey is cornered and so is the king. If we suppose that they’re each employing their strategies of last resort, there are not very many possible outcomes. What’s more, the Ruvik Alliance is also involved.”

Col gulped and hesitantly asked another question. “Will Miss Holo be all right?”

This cut to the heart of the matter; it was like a wound—when touched, some would groan in pain, and others would bellow in rage.

Lawrence was the former. “…This is unbearable for her, and she was unable to accept things as they are, so that’s why she spoke as she did. But so long as the situation permits, she’ll offer her help. Despite how she might look, she’s quite kind. Which you’re supposed to find surprising, by the way.”

Col wrapped Huskins’s feet in cloth to prevent frostbite, then added another log to the fire. Finally, he gave a tired smile.

“She knows perfectly well how unsightly her jealousy is. In the face of Huskins’s resolve, she must’ve felt like a child. Her pride as a wisewolf has been terribly wounded.”

Holo’s pride and vanity were second to none, but she also knew when to joke and when to act in earnest. And when she was in earnest, even Lawrence had to acknowledge her excellence.

“I once told Holo something.”

“What was that?”

“That there are many different ways to solve a problem. But once it’s solved, we must live our lives. Which means we should choose not the simplest solution, but the one that will allow us to feel most at peace once it’s done.”

Huskins was wrapped in a blanket so not even a bit of drafty air could reach him. In place of a pillow, they wrapped a piece of firewood in another blanket and placed it under his head, finishing their care of him.

“And when I told her as much, she called me a fool. As though giving up on me. But I wonder if she could really abandon Huskins and move on so easily as that.”

No doubt Col had imagined Holo simply eating, drinking, and curling up like a dog or cat. But Lawrence found it difficult to believe she would abandon someone who had endured such hardship in creating a second home.

Col shook his head once, then a second time, more strongly.

“As for where you stand, it hardly bears saying.” Lawrence smiled, and Col’s face went rigid as though a great secret of his had been revealed. He looked down, ashamed.

Even if Lawrence and Holo had decided to abandon Huskins, Col would not have done it, Lawrence was sure.

“Anyway, so far it’s an emotional argument.”

“So far?” Col’s eyes looked up uncomprehendingly, and even Lawrence found himself wanting to hug him. Having Col around was certainly good for his pride and vanity.

“I’m a merchant, after all. I don’t act unless there’s some profit in it.”

“…Which means…?”

“This notice of taxation. If Huskins’s words and Piasky’s guesses are to be believed, it will wipe out the abbey entirely. Which means this is a perfect opportunity for us. They say before a great wave comes, the sea recedes and lays the ocean floor bare. Thus…”

Col answered immediately. “You’d be able to see all the treasure that used to be underwater.”

“Exactly. If there’s anything there, they won’t be able to hide it. As far as Holo’s original goal goes, this is hardly useless. Although whether she chooses to take it by force will be up to her.”

Col nodded and then slumped over as though relieved. “I’m just not as clever as you are, Mr. Lawrence.”

Col was probably thinking of Lawrence’s ability to see things from many perspectives. Lawrence’s wordless smile and shrug were no act. If Holo had been there, she would have known.

Not many humans could lie to themselves, after all.

“The night is long, and we have a fire. Col—”

“Yes!”

“Lend me your wisdom.”

“Of course!” Col shouted and then hastily covered his mouth.

Lawrence made ready a pen and paper and began to draw up a plan.

The movements of an insect’s wings are hard to see, but the wingbeats of a great hawk are easily counted. Thus, a large organization’s actions were easier to predict than a smaller one’s. All the more so when they were cornered.

But good information was scarce.

They knew the abbey was in the midst of a financial crisis. That the king’s failed policies had emptied the kingdom’s coffers. And that the king had decreed a tax that would (and this was supposition) ruin the abbey.

What they did not know was what form the abbey’s final assets would take. Did it have—as Lawrence predicted—a valuable holy relic like the wolf bones, or were its assets in coin?

Lawrence neatly wrote what facts they had on the upper half of the paper. The remaining half listed the choices available to him and his traveling companions.

For example—who should be told of the notice of taxation? The alliance? The abbey? Or should they tell no one?

Next, there were a similar number of choices regarding how to deal with the story of the wolf bones.

Their options seemed at once too few and too many; the unknown elements remaining were likewise. The monastery was in a financial crisis, and even if the leaders were unable to survive another round of taxation, there was no way of knowing whether they would stubbornly defy the kingdom or meekly do as they were told, submitting to the threat of military force like so many sheep.

Realistically speaking, there were no options Lawrence and company could pursue entirely on their own.

Perhaps their only real choice was to go to the alliance with what they knew, carefully trading small pieces of information in order to expand their knowledge, then force their way into the proceedings somehow.

Of course, there were risks. But victory was not impossible.

After all, even if the alliance had the abbey by the throat and was trying to somehow tear it out, they were not some clumsy mercenary band that would devour the carcass all the way down to the bones.

Just as they knew how to harvest wheat, they knew how to increase their harvest. They were perfectly aware that a steady stream of small profit was better than a single great gain.

And because a successful harvest required stable land, the abbey’s continued existence would be a high priority for the alliance. They were surely looking for a solution that ensured the abbey would go on.

Lawrence and Col passed the night thinking the problem through, top to bottom. They considered each and every possibility, deciding whether it was worth the risk. The raging blizzard and cold before the dawn kept their thinking sharp—or perhaps it was Lawrence’s understanding of the way the world worked, combined with having Col at his side.

Around the time the hearth fire was quietly burning itself to ash, Lawrence and Col had found a miraculous possibility and written it on the paper.

Holo’s happy face and Huskins’s surprised eyes greeted him as he revealed the plan to be—

“…—”

He triumphantly presented his conclusions to Holo. And that very moment, he woke up.

The charcoal fire and the falling snow sounded very similar to each other. Lawrence tried to estimate from the crackling sound how long he’d been asleep.

The only thing he could not remember were the specifics of the miraculous plan. No—he understood now.

It had been a dream, and worse, that he had had exactly that sort of dream was now written all over his face.

“Fool.”

He was slumped over the crate on which he had been writing; when he sat up, Holo was crouched by the hearth.

The word echoed more pleasingly in his ears than any church bell could.

He yawned hugely. His neck hurt terribly, probably from the strange sleeping position.

“You fool…”

Two blankets were covering him.

Holo turned away from him as she called him a fool; next to him was Col, curled up and seemingly clinging to Holo’s tail.

Her face was hollow-cheeked, probably because she had cried herself out not long before. Or perhaps she was just cold; she was not wearing her robe.

Lawrence finally realized it was not so much her appearance as it was the general atmosphere that made her look poorly, and just then Holo sighed and spoke.

“Aye, how lucky I am.” Her words and expression were completely unrelated, and yet she seemed to speak even more truly than she did when praising a piece of fatty mutton. “This world so often does not go as one would wish, and still.”

With his mouth half-open and his sleeping breath utterly silent, Col almost seemed dead at a glance. But when Holo gently stroked his head, he shrank away ticklishly.

“Our God tells us to share what we have with others,” said Lawrence.

“Even our good fortune?” Holo asked, bored.

If he misstepped in his response, he was quite sure he would receive a cold sigh in response, along with a disinclination on Holo’s part to listen to him further.

“Even our good fortune. I think I’ve put that into practice quite nicely.”

“…”

“I even let Col use that tail of yours,” he said quite seriously.

Holo only smiled a defeated smile, then smoothly moved her gaze over to the window.

“My body felt as though it were aflame.”

“Was that—”

“—because of what I said?” Lawrence was about to jokingly finish, but could not bring himself to.

But Holo realized how his joke would end and seemed surprisingly happy at it. Her ears flicked, and though she still faced away, her shoulders shook with laughter. “Ah well, all creatures are alike in that they tend toward selfishness. It has been a long time indeed since I’ve felt such envy for the belongings of another. ’Tis almost comforting.”

Lawrence paused before replying, to make it clear that what he was about to say was in jest. “Well, of course it was comforting—it’s always a comfort to be so childishly selfish.”

Holo was not the type to kick away someone who was begging at her feet. It was her nature to try to grant any favor asked of her, no matter if it did her no good, no matter if it angered her—that was why she had stayed in Pasloe for so many centuries.

“Humans and sheep think the same way.”

“Enough for you and I to argue about it certainly.”

“Mm. Unless we fight over the same thing, curse each other with the same words, and glare at each other from the same height, it is not a true fight.”

She sat and stroked Col’s head, occasionally laughing as she spoke, the breath rising in white puffs from her mouth. Lawrence could imagine her as the goddess of some forest, so elegant and gentle her form.

Unlike when she was bundled up in layers of clothing, her slender frame seemed unrelated to any idleness or debauchery.

Lawrence regarded not a weak girl who needed his protection, but the ancient wisewolf Holo, god of the harvest who lived in the wheat.

“I have a little wisdom and experience. Col has intellect and imagination.”

“And what do I have?”

“You have a responsibility,” said Lawrence. “A responsibility to turn our travels into a tale that will be long told. Isn’t it perfect, the tale of a wolf coming to the aid of sheep?”

For authority to exist, it needed the support of a sturdy system of values. Taking responsibility for one’s words was exactly that.

Holo opened her mouth, and from between her fangs issued another large puff of vapor. She smiled, amused.

It was the childish smile of the scheming prankster. If one were lost in the woods and being attacked by bandits, if there were anyone to call upon for aid other than God, it would be someone with this very smile.

“Is there any chance for victory?”

Lawrence did not reply, only shrugging and handing Holo the paper upon which he had been sleeping. Holo looked at this face and laughed—no doubt it was smudged with ink.

“I have a measure of confidence in my own cleverness…but this sort of situation is not my specialty.” She must have been referring to broad, encompassing ways of thinking. If one could always rely on might to solve one’s problems, there was no need to consider the fine details of a situation. “Of course, an old mercenary general once said that one cannot continue winning battles with a single strategy. Constantly shifting tactics are the best way to defeat one’s opponent. And—”

“And?”

“Only the gods are capable of that.”

It was a mischievous joke.

“Remember that,” Holo’s expression seemed to say, yet she did not appear at all displeased.

“The question is whether the abbey does in fact possess the bones. And that seems very likely.”

“Yes. Nothing else fits the story Piasky told us so perfectly.”

“You should ally yourselves with the pack you already know, not the abbey, don’t you think? Nothing is so frightful as an ally whose thoughts you cannot divine.” As she spoke, Holo’s eyes flicked over the scrawled writing on the paper, where Lawrence had written the results of his talk with Col, reading it with great speed.

They had once fought mightily when Holo pretended to be illiterate, but now Lawrence wondered if she was a swifter reader than he.

“Yes. The men of the alliance aren’t fools, and given the men like Piasky in their employ, they want stability for this land. Huskins and his people may find their territory a bit smaller, but their goals are similar.”

Holo narrowed her eyes, like a wealthy noblewoman evaluating a precious gem, but her gaze was directed at Huskins, who still slept by the fire.

But when she realized that Lawrence was watching her, she looked back at him and grinned in embarrassment.

Lawrence was too frightened to make sure, but he guessed there were more years separating Huskins and Holo than their appearances would suggest. Holo’s sense of duty and her queer integrity probably led her to give Huskins a measure of respect for his greater experience, even if he was a sheep.

For Holo, extending a helping hand to another might not have sat well, even as she took pride in it.

“So what can Kraft Lawrence, a mere traveling merchant, hope to do here?”

She so rarely called him by name that to hear it felt to Lawrence like something of a reward in and of itself, which he had to admit was strangely pathetic.

Lawrence grinned a fearless grin, like a man challenged to drink a cup of strong liquor in one go. He took a breath and answered slowly. “The wolf bones must be of crucial importance to the other side. Our information points to them as being the only real possibility. So the information will be taken very seriously, and the greater its potential to break the stalemate, the more seriously it will be taken. And that’s where traveling merchants like me have room to maneuver.”

“And this is the way of it truly? Are you sure this is correct? Will all truly be well? Truly? For certain? I believe you—I trust you, I do.” Holo laughed as she posed her childish questions.

Lawrence took in each one, elbow propped on the crate, with the poise of a proper merchant. “In exchange for the proof, I’ll ask you to hear a few of my questions, as well.”

“The notice of taxation or whatever ’tis called will make them starved for time.”

“I don’t think they’ll be able to avoid the negotiating table. Once a messenger arrives with the notice, there will be very little time left. If they dawdle, the profit will vanish. Better the coin purse starve than the belly, they say.”

“Hmph.” Holo sniffed as though mocking his optimistic prediction and turned away, unamused. “’Tis well, I suppose.”

She thrust the paper back at him, and Lawrence received the royal decree politely, rolling it up like a nobleman given an order from the king. “Well, then, so be it.”

And with those words, Lawrence was again a merchant—slave to contracts, servant of coin.

And one of the hidden kings that controlled the world from the shadows.

“Now, then.” Lawrence had neatened his beard, combed his hair, and straightened his collar.

Everything had to be perfectly in order before commencing with a business plan, though he was well aware that nothing truly proceeded according to plan.

The first problem would be finding a way to make the Ruvik Alliance take the bait of the story of the wolf bones. If he could not succeed in doing that, nothing else could happen.

“I suppose I’m off.”

Seen by an outsider he would have seemed a dwarf about to enter a giant’s lair—but back when he had been first starting out, every merchant had seemed a giant to him. He had managed to survive among them, so he would manage this, too. Holo and Col saw him off, and he put the shepherds’ dormitory behind him.

Still suffering from the effects of his march through the blizzard, Huskins was not yet recovered, but his color improved noticeably upon Lawrence informing him that he planned to cooperate.

Huskins had always supported the abbey in secret, so as far as the abbey was concerned, he was a shepherd like any other.

Thus, it was probably true that the only person Lawrence could count on was himself.

Conditions outside were still awful with buildings mostly covered in snow. Only a few eaves were still visible with small patches of stone or wood managing to peek out.

But even in such conditions, no merchant could simply sit still and wait. When Lawrence finally arrived at the alliance inn, another man was returning there from the building across the street.

“Ho! To think we’d have a customer so early, even in this weather.”

“Of course. The worse the weather, the larger the gain.”

“Ha-ha-ha. Too right!”

Perhaps he was a member of the Ruvik Alliance; he did not hesitate to open the door and hurry inside.

Lawrence followed behind him. One of the merchants just by the entrance asked, “Looking for Lag?”

Evidently they had already remembered him. “Is it written so obviously on my face?” Lawrence asked, rubbing the face in question.

The man laughed. “You’ll find him in the study.” Given that the man who minded the front door looked like something of a theology scholar, no doubt the word study was an apt one.

“My thanks to you.”

“Here for business?” It was the standard merchant’s greeting.

Lawrence smiled pleasantly. “Indeed. Big business.”

Then he was out in the snow again, making his way to Piasky’s place of work.

Lawrence told the theology scholar–seeming man at the front desk that he wanted to see Piasky, and the man disappeared inside without even asking Lawrence’s name.

His job was probably to watch for spies coming from rival alliances. As Lawrence was considering the possibility, the man returned and wordlessly gestured inside.

Lawrence bowed and proceeded in.

As he approached, Piasky opened the door and waited for him.

“Good morning to you.”

“And to you. What brings you here?” said Piasky, closing the door behind Lawrence as they entered Piasky’s private room.

Piasky was surely aware that Lawrence would not brave the terrible weather for idle chitchat.

Lawrence patted off what snow still remained on him, cleared his throat to conceal the nervousness he felt, and put on his best merchant’s smile. “Actually, something happened last night that bothered me.”

“Bothered you? Please, have a seat.” Piasky offered a chair, in which Lawrence sat, and rubbed his nose. He opened and closed his hand, dropping his gaze to it. It was an obvious affectation, but that was probably appropriate.

“Yes. It was so extraordinary that I couldn’t sleep at all for thinking it over,” said Lawrence, pointing to the bags under his eyes.

A merchant that came to a negotiation with tired eyes could not help but be regarded with a healthy measure of suspicion. But Piasky simply laughed. “Oh?”

The blizzard outside raged, and the stalemate continued. An extraordinary tale was the perfect companion for some wine.

“Whatever could it be? Don’t tell me you’ve found a way to break the abbey’s resistance.”

This was the moment to strike. “Yes, that’s it exactly.”

The smile on each man’s face froze, and Lawrence did not know how much time passed like that.

Piasky rubbed his hands several times, his expression unchanging, then silently rose and opened the door.

“And?” he asked, a split second after closing the door again. Evidently Piasky was something of an actor himself.

“Are you familiar with the port town of Kerube, across the Strait of Winfiel?”

“I know it. It’s a trade point between the north and the south. I’ve never conducted business there, but the delta there is a fine place.”

“Quite so. That’s the town. Are you familiar with a silly rumor that arrived there around two years ago?”

Piasky was a merchant who lived on the road, so he might not have heard of it—or so Lawrence thought—but Piasky made a face as though something had just occurred to him and then put a finger to his lips. Was he going to speak his mind?

“As I recall…something about the bones of a pagan god?”

“Indeed. The bones of a wolf.”

Piasky looked off into the distance, as though thinking something over. When he looked back at Lawrence, his gaze had become guarded, as though genuinely surprised he had brought up something so unlikely.

“And what about those bones?”

If Lawrence had to guess, Piasky’s humoring manner meant that he was either making fun of Lawrence or he simply found the situation completely absurd.

Lawrence nonetheless mustered up the energy to reply. “Suppose the abbey purchased the bones.”

“The abbey…?”

“Yes. Even if they are the bones of a pagan god, they could be used to reinforce the authority of the Church’s God. They could be used to preach to all who gather in the sanctuary to pray for salvation, and they could be treated by the abbey as an investment, becoming something for those searching for a practical way to break the deadlock to cling to.”

Piasky let Lawrence finish, then closed his eyes, his expression bitter—and not because he was taking Lawrence’s statements seriously. He was surely considering how to gently reject the idea.

“I think that even if wool sales have been falling over the years, it would take a certain amount of time for the situation to become this dire. The abbey would have chosen a way to shelter its assets years ago because the nation’s coin has been falling in value all along. For one, they would buy up goods with that coin—if possible, goods that could be sold anywhere in the world for about as much as they’d been bought for. That way, if the local currency did indeed crash years later, the abbey could sell the bones for foreign currency and then bring that coin back to this kingdom. And just as we were able to stay at that fine inn in Kerube, they’d be treated as the richest men in the land.”

Piasky seemed sincerely troubled by Lawrence’s froth-mouthed explanation.

“What say you?” Lawrence asked.

Pressed by Lawrence, Piasky held up a palm as though to say, “Wait, I’m too shocked to speak.”

When Piasky finally did speak, it was after clearing his throat three times. “Mr. Lawrence.”

“Yes.”

“It’s true that what you’re saying seems plausible.”

“It does,” Lawrence said with a happy smile. He was well aware of the sweat breaking out on his brow.

“But we are the Ruvik Alliance. That is…This is difficult to say, but…”

“What is?”

If Holo had been there, Lawrence was sure her eyes would have gone round at his acting.

“Well, er, I’ll be blunt. We long ago considered that possibility.”

“…Huh?”

“It’s a well-known rumor. And well—” Piasky sighed as though he simply couldn’t stand to hold back any longer. “Truly, many people, many of our brightest comrades have put their minds to this problem.”

Lawrence fell silent, still leaning forward.

Piasky spread his palms and looked at Lawrence out of the corner of his eye.

Lawrence looked away, then looked back at Piasky, and then averted his eyes again.

A gust of wind rattled the windows’ shutters.

“We concluded that no such relic existed. When the story first appeared, one of our men was in Kerube at the time, and he looked into it through a company we’re connected with there. What he found was that only a single other company was searching for the bones, and it was a half jest even to them. They didn’t have the size to purchase a true holy relic, nor did they have such funds. It was just to improve their reputation. Such things happen, you know, after drunken boasting in taverns or exchanges of jokes.”

His long-windedness came from anger, it seemed. Anger at having had his time wasted.

Or anger at having hoped for more and been made a fool of.

Lawrence had no response. He shifted in his chair, rubbing his hands uneasily. An awkward silence descended.

“It’s just a fairy tale,” Piasky finally spit out with disdain. Lawrence pounced.

“And what if it isn’t just a fairy tale?” Had he been unable to smile as he said it, Lawrence would have been a third-rate merchant.

He grinned. He pulled his chin in and looked at Piasky with an upturned gaze.

“…Surely you jest.” Piasky was then silent for a while before replying, and while his expression feigned placidity, Lawrence did not fail to miss the way he casually dried his palms.

“I will leave it to you to decide whether I am in earnest or not.”

“No, Mr. Lawrence, you must stop this. If my reply was unfair, I apologize. But we’ve all thought this through together very thoroughly—that’s why I lost my temper. So please—”

“So please don’t upset you by saying such baseless things?”

The shutters rattled, and the windblown snow audibly impacted against them. It sounded like a ship being battered by waves, and Piasky’s face was starting to look distinctly seasick.

He bit his lower lip and widened his eyes, his face paling.

“Fifteen hundred coins.”

“What?”

“How many crates do you suppose it takes to hold fifteen hundred gold lumione pieces?”

Lawrence could still clearly remember the image of the Jean Company proudly carrying a mountain of crates into the church.

Piasky’s face twitched into a stiff smile. “M-Mr. Lawrence.” A trickle of sweat left his temple and rolled down his cheek.

Facial expression, tone, even tears—all of these could be feigned by a skilled actor.

But sweat was not so easy to fake.

“What say you, Mr. Piasky?” Lawrence leaned forward in his chair, bringing his face close enough to Piasky to tell what he had eaten for dinner the previous night.

This was the moment of truth.

If Lawrence couldn’t snare Piasky here, his claws would never reach his next prey.

“I’d like to continue to use you for all contact with the alliance.” Piasky would surely understand what he meant. He gazed at Lawrence fearfully, like a pilgrim with a blade held to his throat.

“We can break this stalemate. I’d like you to take that critical role. It’s not such a bad proposition, is it?”

“B-but…” When Piasky finally spoke, his words smelled of fine wine. “But do you have any proof?”

“Trust is always invisible.” Lawrence grinned and drew back.

Thus mocked, Piasky started to turn red, but Lawrence quickly continued and headed him off.

“The abbey wouldn’t be so foolish as to write ‘wolf bones’ in their records. They would make up some other term and record that instead. But nothing can stay hidden forever. If you read over the records expecting to find nothing, nothing is precisely what you’ll find—but if you suspect something of being hidden and look again, things may be different. What say you, eh?”

Piasky had no reply. He seemed unable to.

“To be perfectly honest, I happen to have something that lends some credence to the story of the wolf bones. But truthfully, it’s too big a story for a traveling merchant like me. If I told this directly to the alliance officials, there’s no telling whether they’d trust me or not. I need someone to vouch for me.”

Lawrence had brought goods from far-off lands into many towns, and he had built up some experience with such situations. Having someone local to the town or village agree with his sales pitch could make a tremendous difference.

Lawrence was not so naive as to believe that simply telling the truth was enough to earn trust. A single person might not be able to sell even the finest goods, but two people could make a killing selling nothing but trash.

That was the truth, and it was the secret to trade.

“But…”

“Please think it over. I did manage to win Mr. Deutchmann’s trust in the port town. Me—nothing more than a simple traveling merchant.”

Piasky breathed out a pained chuckle and then closed his eyes.

Lawrence had heard that particular saying came from the capital of the great southern kingdom, whose trade network had grown over the decades into a net that covered the land, like a great spiderweb. Lawrence had never visited the city, but he could feel the truth of those words: Trust is invisible.

It was invisible, yes, but it could not be ignored.

“Mr. Piasky.”

Piasky trembled when Lawrence spoke, and a few drops of sweat fell from his chin.

If the wolf bones were real and not a fairy tale, then helping Lawrence would be a good way for Piasky to get promoted. But if they were the ravings of a mad traveling merchant and Piasky let himself believe in them, they would be his undoing.

Heaven or hell—if their sum was zero, then the only thing to be gained by getting involved was the thrill of the gamble. When the price of failure was ruin, anyone would hesitate, given enough time to do so.

And hesitation often gave rise to fear.

“…I just…I simply can’t…” Piasky agonizingly forced the words from his mouth, even as he wondered if what Lawrence had said was true.

He was escaping!

Lawrence had no choice but to block his path.

“What if—” said Lawrence with a voice as sharp as a needle, but then he hesitated. If he said what he was about to say, there would be no turning back from the path it would lead them down. Lawrence swallowed and continued, “What if I told you the king was taking action?”

“Wha…huh? What—what sort of…?”

“A tax.”

He had said it.

Piasky’s face went blank, and he stared at Lawrence. But unlike his dumbfounded face, his mind was surely calculating at unbelievable speeds.

Piasky stood swiftly from the chair. But Lawrence would not let him escape. “What good will it do to tell them now?”

As he shook his arm to try to free it from Lawrence’s grasp, it was obvious where Piasky was headed.

No matter the group, loyalty made its members into dogs. It was natural to assume Piasky was running to deliver the crucial information to his betters.

“What good—? I must inform them immediately!”

“Inform them? And then make a plan?”

“That has nothing to do with you!”

“Even though you long ago lost your hand to play?”

“…!”

Piasky’s resistance ceased. The pained look on his face showed he knew Lawrence was right.

“Please calm yourself. Even if you did tell the alliance of this, you would only be needlessly worrying them. If a new tax comes, the abbey will be ruined. And when that happens, they’ll choose between falling to their knees before the king and begging for mercy or dying valiantly. But if someone reveals that the abbey has a pagan item like the wolf bones, what do you suppose the abbey will conclude?”

The abbey could not escape its own land, and the land could not escape secular authority. So what would happen if in order to pay taxes, it asked for help from the Ruvik Alliance, which was openly working against the government?

The king would call it treason and send in the military.

And even if it came to that, the abbey still had a final hope—it was still a part of the Church. But if the truth of the wolf bones was revealed, that last hope would be taken hostage.

If a clergyman were asked which choice was the worst for the king or the pope, like anyone affiliated with the Church, he would answer the latter.

And that would be the moment that would give the alliance a chance to strike.

“Mr. Piasky, the time left to us is dwindling, and we will only have a single opportunity. Before all descends into chaos, we must put this attractively mad idea to the powers that be. And even if we don’t have their agreement, we’ll have their attention, so when chaos does fall, we’ll be easier to notice. After all, a drowning man will reach for whatever’s nearest. I’m optimistic enough to think this will succeed. You see—”

Lawrence moved around the table and stood before Piasky.

“—I’m quite certain the story of the wolf bones is true.”

Piasky’s eyes fixed upon Lawrence. He was not glaring—it was as his gaze had been nailed there.

His breathing was ragged, and his shoulders rose and fell violently.

“Mr. Piasky.”

Piasky closed his eyes. It looked like a gesture of defeat, as if Piasky was telling Lawrence to do whatever he wanted, but as his eyes closed, his mouth opened and he spoke.

“What proof do you have that this tax is real?”

He had taken the bait. But the hook was not yet fully set.

Suppressing his urge to pounce, Lawrence responded slowly. “I’m staying with the shepherds at the moment. When something gets dropped outside, I can be the first one to see it.”

Piasky shut his eyes tightly and took a deep breath through his nose. He was probably trying to cool his head. Those gestures alone were all the proof Lawrence needed to know his words were having the desired effect.

“When did this happen?” Piasky asked.

“Late last night. That’s one of the reasons I couldn’t sleep.”

Piasky gritted his teeth with such force that Lawrence felt sure he could hear the grinding. If the taxation were real, the town would instantly turn into a stick-poked hornet’s nest as soon as the news was delivered. And at that point, no further proposals would be heard.

In other words, there would no longer be anything anyone could do.

Lawrence was sure that Piasky knew that much, so he did not say anything further. A merchant could wait all night for a scale to tip if it would win him profit.

There in the silence peculiar to snowfall, time passed.

Sweat beaded on Lawrence’s brow.

Piasky slowly opened his eyes and spoke. “Fifteen hundred pieces.”

“Huh?”

“Fifteen hundred pieces of lumione gold. How much volume did that come to?”

Lawrence relaxed his tense expression in spite of himself, but not because he thought Piasky’s question was foolish. It was the proof that they had made a contract.

“I won’t let you regret this,” said Lawrence.

Piasky burst out laughing at this, looking upward momentarily as though in prayer, then wiping his sweat-soaked face with both palms. “Fifteen hundred pieces of gold. I’d like to see that much just once in my life.”

Lawrence extended his hand. He could not help saying it. “You will. If all goes well.”

“I’d best hope so!”

The first barrier had been passed.

No Comments Yet

Post a new comment

Register or Login